Walkabout: Brokers, Lawyers and Larceny at 88 Decatur Street, Part Four

Read Part 1, Part 2, Part 3, Part 5, Part 6 and Part 7 of this story. As the cynical and world-weary people we can be today in 2014, it doesn’t really surprise us when those who are entrusted with much, or are held up as paragons, fail spectacularly. Sadly, we see it almost every…

Read Part 1, Part 2, Part 3, Part 5, Part 6 and Part 7 of this story.

As the cynical and world-weary people we can be today in 2014, it doesn’t really surprise us when those who are entrusted with much, or are held up as paragons, fail spectacularly. Sadly, we see it almost every day. But 100 years ago, life was simpler. Back then, (and now, as well, to be honest), people expected certain criminal activities like thievery and dishonesty from the classes and groups they felt were beneath them. But they held the upper classes to a higher standard, one of dignity and success through hard work and privilege. Therefore, when one of their own was suspected of, or caught doing wrong, the stories fascinated the newspaper reporters and their editors, as well as the general public. The fall of a prominent lawyer, or a banker, was news for days.

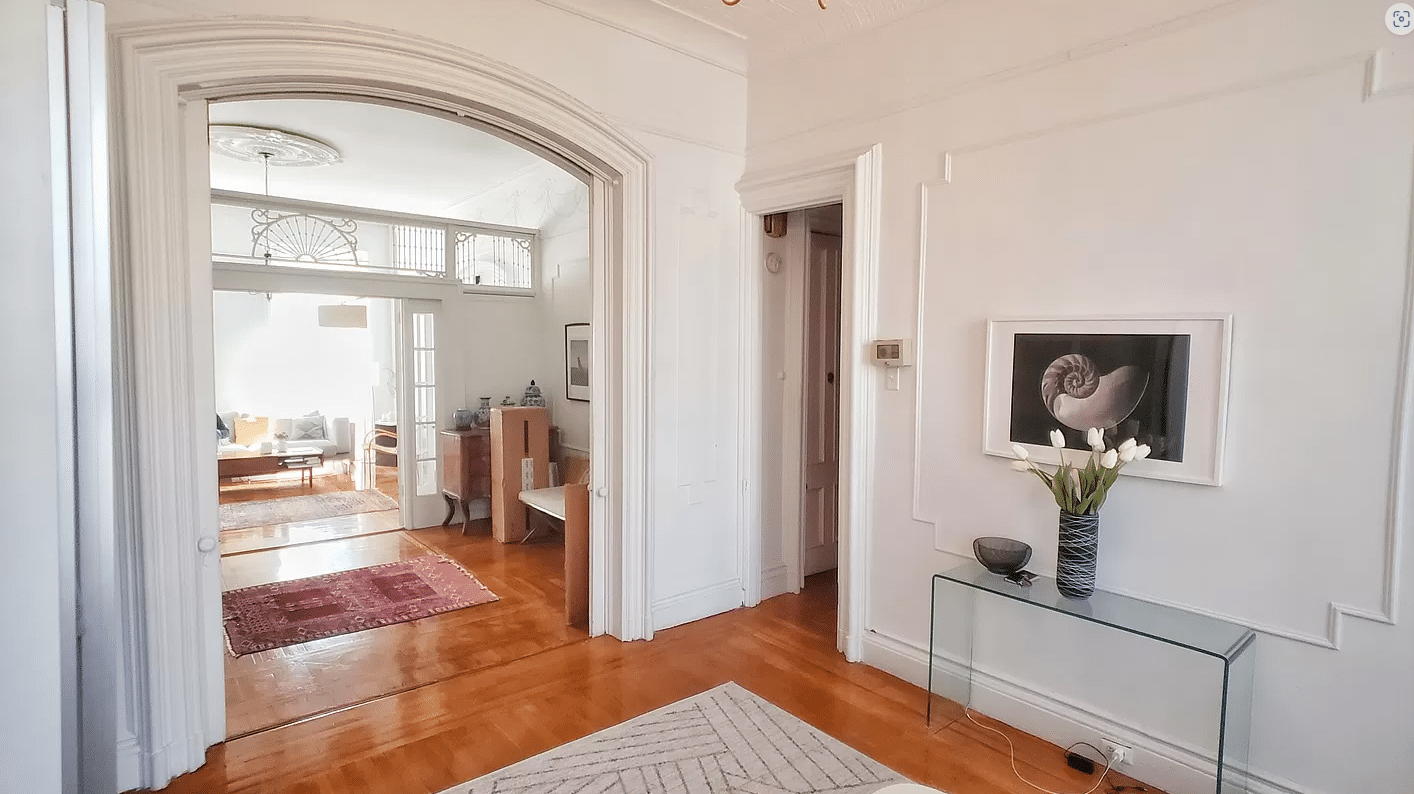

We met Benjamin F. Chadsey last time, the scion of an important Albany area family, and an up and coming lawyer here in Brooklyn at the beginning of the 20th century. He lived here in Brooklyn with his wife at 88 Decatur Street, in an upscale apartment building in Stuyvesant Heights. Like another occupant of the same apartment house, J. Edgar Anthony, the topic of our first story from this building, young Chadsey was also an attorney who worked in estates, wills and trusts. Mr. Chadsey had a fine reputation in the law, and was a rising star in the world of Brooklyn Republican politics. Benjamin Chadsey, it was said, could persuade you to vote for anyone, and his silver tongue was put to use at political rallies all across the city. He was soon on a first name basis with some of New York’s most important Republican political figures.

Unfortunately, Chadsey was arrogant enough to think that he knew best in the matters of his clients, as well as the voters, and had been playing loose with some of his client’s money. He had been administering the estate of Daniel M. Collins, a wealthy Brooklyn Heights jeweler. The deceased Mr. Collins’ wife suspected that her brother-in-law and Chadsey had conspired to cheat her out of her inheritance, and that Chadsey had grossly overbilled her for services rendered. The widow retained another lawyer, and filed suit. A judge agreed, and had chastised Mr. Chadsey, and ordered him to pay back about $900 in overcharged fees. That may not seem like much in today’s money, but in 1902 it was around $20,000 worth, certainly enough for most of us to file suit.

By the time the news hit the papers, Benjamin Chadsey and his wife were already gone. They had quietly packed up their apartment, removed their most important papers and objects, and went on a lengthy vacation on a steam ship to South America, ending up in San Francisco, months later. In the meantime, another client had gone public with a complaint, and a bench warrant was issued for Chadsey’s arrest. His movements were traced by a private detective named J. Edward Orr, and when the Chadsey’s disembarked in San Francisco, the detective was waiting at the bottom of the gangplank. Vacation was over.

Back in Brooklyn, Benjamin found himself big trouble. He probably would not have been had he stuck around and faced the charges in the first place. His partner in the Collins case, John Collins, had sold the jewelry store and its contents and had also skipped town. He was in jail for a number of charges, but although he had colluded with Collins and had given his client bad advice, Chadsey was only in trouble for not paying back the court ordered $900.

However, another client, Miss Isabella Miller, had also filed right before Chadsey left Brooklyn. She was the guardian for a minor, a boy named Louis Meyer. Chadsey had represented young Meyer in an accident case, where he had won $1,800 for his client. But he had not turned over all of the agreed upon money to his guardian. She was short about $900 too, and after trying unsuccessfully to get him to pay up, had taken the case to the court. Benjamin Chadsey was possibly going to jail for a paltry $1,800, having committed the more heinous crime of stealing from a client and putting his agenda before theirs. If you can’t trust your lawyer to look out for your interests, well…

It was now March, 1903 Benjamin Chadsey was set to go to trial in the Miller-Meyer case. He had been released on a high bail after being returned to NY, for the Collins case, in order to secure his presence at trial. Chadsey still had quite a large practice and lots of clients, and was his usual fixture at Brooklyn’s courts and chambers. But in March, Chadsey disappeared again, this time on the night before his trial was to begin. His wife did not accompany him this time, and swore she didn’t know where he was. She was quite distraught and beside herself with worry over him.

Rumors began to circulate that Chadsey had committed suicide. On the evening of March 16th, the night before the trial, Chadsey had been in the company of a boatman named John O’Connor, who operated a boat service on the Battery, in Manhattan. He told investigators that Chadsey had come to his slip and wanted to go the Bedow’s Island. He offered to pay $10 for the round trip. But before the trip, the lawyer invited O’Connor to have a drink with him, as it was a cold night. O’Connor agreed, and the two men went into a nearby tavern and had many drinks. Chadsey was well dressed, and had plenty of money, and was soon a favorite in the tavern, as he bought O’Connor and a group of his newest friends drinks well into the evening.

Finally, Chadsey insisted that they had to go to the island, and he and O’Connor went back to the boat. Chadsey was having trouble walking and almost tipped the boat over, but finally settled in, but before they could set out, he decided they had to have cigars. He stumbled out of the boat, and told O’Connor he was going to be right back. He didn’t return right away, so O’Connor decided to buy some more alcohol to fuel the trip. He too, had trouble walking, and when he finally returned, about an hour later, he found Chadsey’s fine silk top hat on the seat, as well as some legal papers, but there was no Chadsey.

O’Connor got himself together enough to run to the police station. An investigation turned up nothing; they even dragged the bottom looking for a body. Although the slip was only about three feet deep at the mooring point, the bottom dropped off a few feet out, and if Chadsey had indeed gone in the water, drunk, he could have been carried out to sea, and it could take days before his body washed back into shore somewhere. The papers reported that Chadsey may have committed suicide rather than face a trial and possible disbarment.

However, the police weren’t buying it. It was just too staged: the drunken evening with witnesses, the hat in the seat, and most especially the papers left on the seat clearly identifying Chadsey. They may have been born at night, but it wasn’t last night. Mrs. Chadsey didn’t believe it either. She maintained that her husband was still alive somewhere, and would come back. Needless to say, the $2,000 bond was revoked. It had been paid by another lawyer, J. R. Caulkins. No doubt, he wasn’t happy either.

Over the next few weeks the rumors and stories persisted. One of the assistant DA’s in the Brooklyn court reported that Chadsey had come to him several times in the months before his disappearance. The usual dapper and well-dressed lawyer had come to the ADA disheveled and messy, his collar coming out of his shirt. He complained loudly, ranting about minor things, such as having to pay a usual fee for filing papers, and seemed to be coming unraveled. He had obviously been drinking. The ADA’s boss was not happy that his subordinate had never passed along these visits to him. Chadsey seemed to be losing it, something he would have liked to have known.

Then in June, a body washed up on shore. It was badly decomposed, but was the same general height and appearance as Benjamin Chadsey. The papers reported that it seemed that the lawyer had committed suicide after all. A weeping Mrs. Chadsey identified the body as that of her husband. The case seemed to be over, but police and the DA’s office never believed it. When further examination proved that the body was not Chadsey, they quietly continued the search. Several years would pass.

In 1905, investigators in South Bend, Indiana arrested a man named Paul Hamilton. He worked for the National Clearance Company of Chicago, an insurance company. His real name was Benjamin F. Chadsey, and he had been a fugitive since 1903. The arresting detective was J. Edward Orr, the same man who had arrested Chadsey in San Francisco in 1902. He had spent the last three years carefully and quietly tracking down his quarry, and he finally caught him.

Chadsey might never have been caught except for love. He somehow had contacted his wife, and she left Brooklyn and went to Indiana to live with him. From there she had written to friends, and through that correspondence, the DA’s office and Detective Orr had found him, made a positive identification, and then proceeded with the arrest. Chadsey was brought back to NY, a very different man that the one that had left.

He was thinner, and had shaved off his signature moustache. He told reporters that he was sick and would not be answering questions. No one could believe that this once rising star in Brooklyn’s legal and political world could fall so far, so fast, and over so little. His friends had put up his bond, and one of his closest friends was now working for the District Attorney’s office and had been a leader in the investigation. There was going to be a lot of retribution coming Benjamin F. Chadsey’s way.

Next time: The end of this case, and the final felonious tenant at 88 Decatur Street. Above sketch of life on a 19th century steamer: hasselisland.org

What's Your Take? Leave a Comment