Walkabout: The Great Forgotten Architect, George B. Post, Part 1

One of the great things about architecture is that one’s works can stand well past the lifetime of the architect; buildings can, after all, last for many centuries, under the right conditions.

One of the great things about architecture is that one’s works can stand well past the lifetime of the architect; buildings can, after all, last for many centuries, under the right conditions. Today, we still enjoy the works of the masters, especially in a city like New York, and there certainly are some impressive masters of the art here. One of the best late 19th century architects in New York, an undisputed master, has almost been forgotten, and is usually not even mentioned in the list of Victorian-era luminaries. A list that includes Henry Hobson Richardson, Richard Morris Hunt, McKim, Mead & White, Carrere & Hastings, CPH Gilbert, Warren & Wetmore, and many, many others, all household names to architecture afficianados, often leaves out the name of George B. Post. And that just isn’t right. During these days of Financial District goings on, it is fitting that we should mention Mr. Post, because he is the architect of the most famous building in the entire district, the New York Stock Exchange. He’s also the architect of the Williamsburgh Savings Bank and the Long Island (now Brooklyn) Historical Society building. But who was he, and why isn’t he better known? And what was the big deal about him anyway?

George Brown Post was born in 1837, in New York City. His family was quite well-off, going back to his grandfather, a very successful merchant. He got his college education at New York University, becoming one of that institution’s first graduates in their fledgling Engineering Department, majoring in both civil engineering and architecture. He was quite a proficient artist, always handy in the pursuit of architecture, and while offered a position as a professor of mathematics at NYU, he decided instead to apprentice himself to the prominent architect Richard Morris Hunt. The year was 1858, and there were no graduate schools in architecture in America. The usual way to become a trained architect was to be apprenticed to an established practitioner. Hunt had a studio in one of the NYU buildings, and Post probably ran into him often as an undergrad.

He couldn’t have chosen more wisely. Richard Morris Hunt was one of the era’s giants, whom the New York Times’ architecture critic, Paul Goldberger, called “American architecture’s first, and in many ways its greatest, statesman.” In addition to his many buildings, including the Great Hall of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Hunt also was a founder of the American Institute of Architects (AIA) and the Municipal Arts Society (MAS), two very important organizations, both quite active to this day. Hunt had received his education at the prestigious L’Ecole des Beaux-Arts in Paris. He was adamant in teaching his young apprentices the importance of the classical influences of architecture, and of perspective. He also was encouraging in a time when architects did not receive the respect of an advanced profession, but were still seen by many as jumped-up builders. Hunt, and some of his pupils, including Post, would help to change that image forever.

George Post took some time off to enlist in the Civil War, becoming a captain of the 22nd Regiment volunteers. He would also serve as an aide to General Burnside in the Battle of Fredericksburg. His stint in the army would end with him receiving the rank of colonel. Ironically, when the 22nd was looking for an architect to design their new armory, Post ultimately did not get the job. After the war, Post continued his partnership with one of his co-apprentices from the Hunt studio, Charles D. Gambrill. They designed several buildings together, and then Post went out on his own. He would have his own firm until he partnered with his two sons, much later in life.

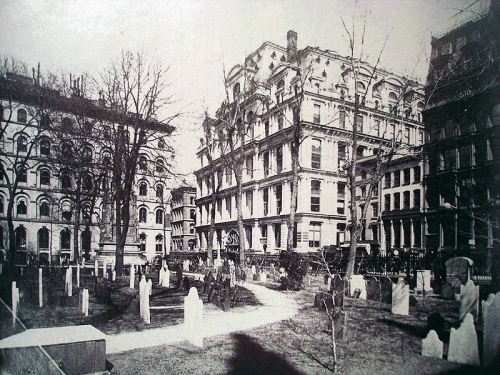

George Post made his reputation on office and commercial buildings, although he did much more, as we’ll see. While some architects hated competitions, often the way many companies and individuals chose a design, Post ate them for breakfast, establishing his reputation from those competitions. Yet, he lost his first competition in 1867, for the design of the Equitable Life Assurance (their word) Society Building, in Manhattan. The panel chose Gilman & Kendall, his competition, as the winners, but was so impressed with Post’s designs as well as his engineering prowess that they made him consulting engineer for the project, as well as project architect. He ended up re-doing much of Gilman & Kendall’s work, especially the structural work, that his name is credited on the overall project. It was one of the first buildings to have an elevator installed, and Post took the credit for getting the project to go to 8 stories, a milestone for the time. The building was so successful that when they expanded it in the 1880’s, Post did the work. Post’s work on the Equitable, and later, on the Western Union Building, also in Manhattan, would earn him the sobriquet, “the father of tall buildings,” the designer of one of the first “skyscrapers” in New York.

Post would design three of the first buildings for the College of New Jersey in Princeton, soon to be called Princeton University, in 1869-70. He designed the gymnasium, called the Bonner-Marquand Gymnasium, a classroom called Dickenson Hall, and a dorm, named Reunion Hall. None of them are still standing today, unfortunately. He came back to New York, and designed one of his Brooklyn masterpieces, the Williamsburgh Savings Bank, built between 1870 and 1875. This bank is an undisputed masterpiece. Post competed with three other architects for the job, and won. The iconic dome and temple front wasn’t new, but Post’s design was so well done, so impressive, that it would become the forerunner and model for the great Beaux-Arts buildings that would dominate commercial and civic architecture in only twenty-five years. The dome alone shows Post’s mastery of engineering and proportion. Post was also a master at choosing artists and craftsmen with an eye for detail and interior perfection. For the bank, he hired Peter B. Wight, who actually had come in second in the competition. Wight’s interior designs and details would, a century later, join Post’s structure as a whole, being one of a very few buildings to be landmarked by both the Landmarks Preservation Commission, as well as the National Register of Historic Places, both inside and out.

Next: More Post buildings, a lot more, including one of my favorite buildings in Brooklyn, the Brooklyn Historical Society. And an answer to the question of why Post is not better known.

sorry, scratch that, Emily Post was the daughter of Bruce Price.

Post’s granddaughter was Emily Post, the original “Miss Manners”.

I do not believe that Post is “forgotten”. He’s pretty well known to architecture buffs – unlike Amzi and Axel, who I had never heard of in my life until I started reading your essays.