Armour-Stiner Octagon House Delights With Over-the-Top 1870s Redo

It’s a bit of 1870s fantasy, with an explosion of ornament (including dog portraits) covering an unusually shaped residence in Irvington, N.Y.

The Armour-Stiner Octagon House in Irvington was restored over several decades and is open to the public. Photo by Susan De Vries

Glimpses from the curving drive give a hint of the curious delight ahead, but the pink confection that is the Armour-Stiner Octagon House never fails to astonish once the trees part and its over-the-top detail is unveiled. It’s a bit of 1870s fantasy, and an explosion of ornament — including flowers, leaves and even portraits of dogs — covers the already unusually shaped residence in Irvington, N.Y.

Restored by preservation architect Joseph Pell Lombardi as a family home beginning in the 1970s, the colorful house has been open to visitors for regularly scheduled tours since 2019. It offers the architecturally curious an escape into Victorian-era extravagance with a painstakingly restored exterior and interior.

The hyphenated name comes from the early owners of the property. Paul J. and Rebecca Armour built the first, likely modest, octagon on the site around 1858. That house was remodeled in the 1870s by Joseph Stiner, a successful tea and coffee merchant, and wife Hannah Stiner, who used the dwelling as their country home.

The pristine condition the house presents to current visitors is all the more impressive considering the alarming state of it by the 1970s. The National Trust for Historic Preservation, which had purchased the property to ensure its survival, sold it to Lombardi in 1978. At the time, once-lavish interior finishes and woodwork were painted white, exterior ornamental details were missing and, most significantly, the dome was threatening to crush the structure.

The slow process of the more than 35-year-long restoration project reflects the benefit of having an architect and family as their own clients. There wasn’t the pressure to finish the house on a specific timeline, which allowed prioritizing the slow winching of the dome back in place and undertaking extensive paint analysis before restoration work commenced.

“The approach was that it had to get done properly,” Michael Lombardi, son of Joseph Pell Lombardi, told Brownstoner on a recent tour through the house. The goal was to be as true to the spirit of the Stiner period as possible, and to do it right even if it meant a longer process.

On the exterior, some of the elaborate details that were missing from the octagon dwelling were actually just tucked away. Carl Carmer, an author who, with wife Betty Black Carmer, sold the house to the National Trust after living there for decades and doing some restoration work of their own, let Joseph Pell Lombardi know that whenever something fell off the house, they just added it to a pile under the porch. Those details were restored or replicated by Lombardi as needed and the vibrant paint colors determined through paint analysis.

The colorful exterior now opens to an equally lush interior, with meticulously researched rooms that still manage to feel like the family home it was intended to be. The interior restoration, undertaken gradually once the dome was secured, included a mix of paint analysis, scholarly research, and the memories of Irvington residents and former owners to make an informed decision about what the house would have looked like during the Stiner period.

Like the restoration, the project of furnishing the interior with period appropriate pieces from circa 1870 to 1876 was also a time-consuming endeavor. There were a few pieces of furniture that survived from the Stiner period, and some hardware and lighting fixtures were still in place to help inform the acquisitions. Some objects took years of hunting to find and acquire, while others were happy discoveries. An Egyptian Revival suite of chairs turned up at auction in 2008 marked with Joseph Stiner’s name, inspiring further collecting of pieces and the decor of the music room on the third floor.

While extensive research has been conducted on the house, there aren’t any known 19th century images or lengthy descriptions of the interior. It is possible that future discoveries may inform the collection of more objects or tweaks to finishes.

A major piece of information that is still unknown is the identity of any architect, builder, or carpenter who may have been responsible for this bit of architectural fantasy.

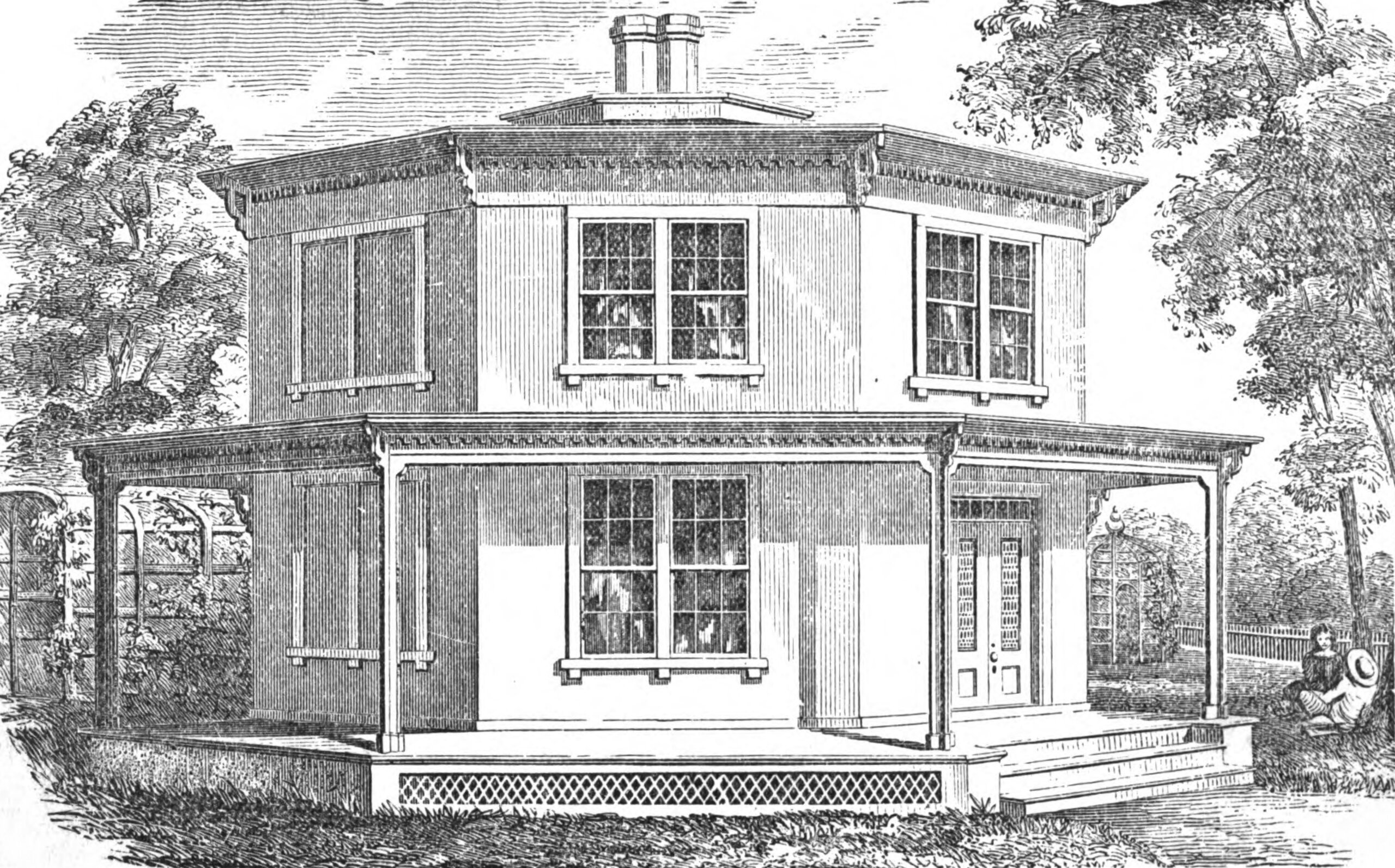

The octagon form itself was no doubt inspired by Orson Squire Fowler’s 1848 publication “A Home for All,” which promoted the octagon as the ideal form for a dwelling. The book was a hit and went through several printings in the 1850s, sparking a flurry of Fowler-inspired houses.

The volume laid out his vision of a house shape that was beautiful as well as functional. It could, in his words, “bring comfortable dwellings within the reach of the poorer classes.” By his calculations, the octagon form provided more floor space for the same expense as a rectangular structure and allowed for more windows, increasing the ventilation needed for healthy living. The sample floor plans published by Fowler show that many of the rooms remained conventionally rectangular in shape — corners were used for closets and pantries. He also included modern conveniences like dumbwaiters, indoor water closets (ideally located under the stairs), and furnaces.

While the octagon fad didn’t last long — most such dwellings were built before the Civil War — it did spread across the country. An inventory by historian Ellen Puerzer found more than 1,000 eight-sided structures were built from Vermont to Alaska. A significant number were constructed in Fowler’s home state of New York, including his own house (demolished in the 1890s) in Fishkill.

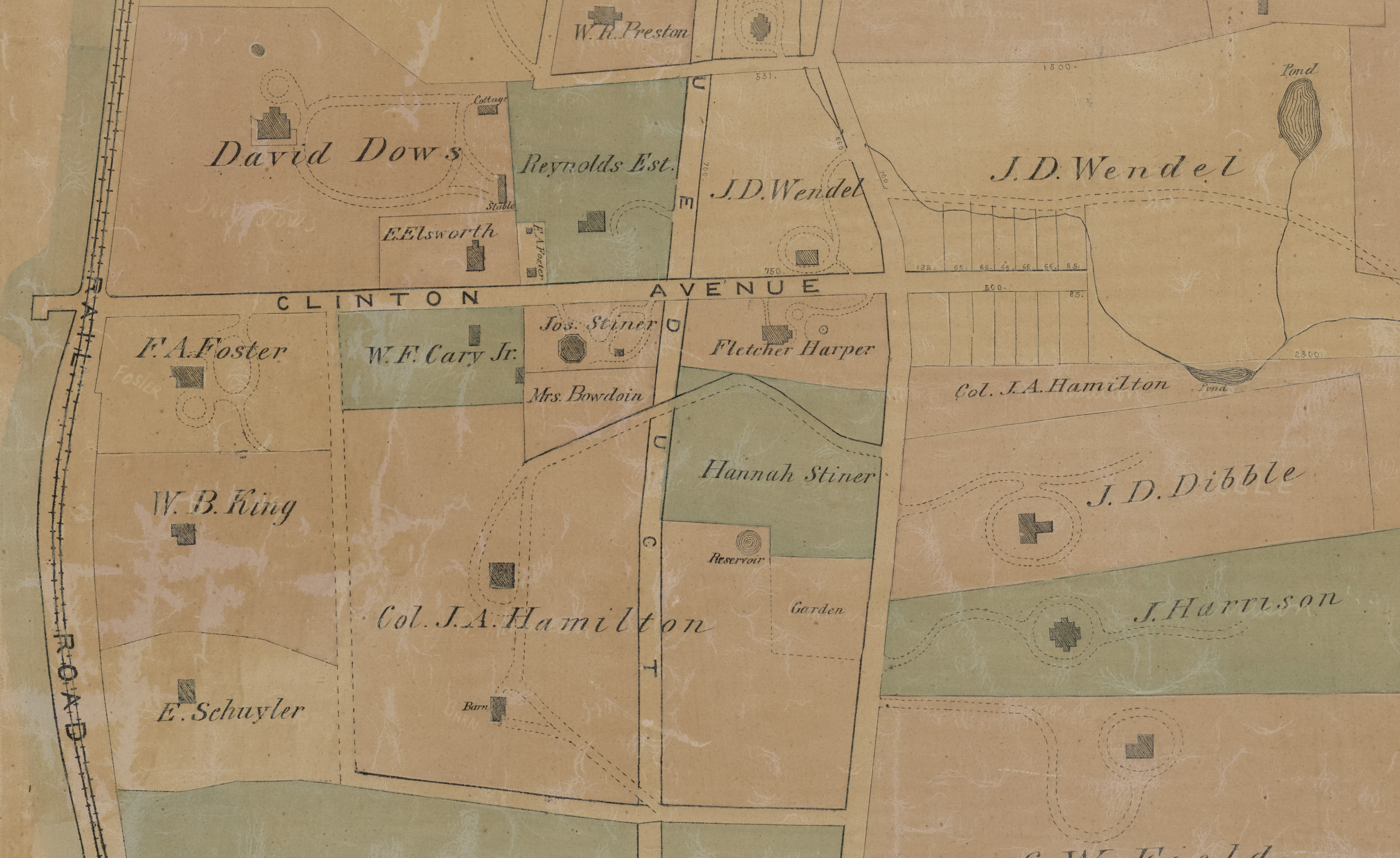

It is believed that around 1858 financier Paul J. Armour built a simple octagon dwelling on the Clinton Avenue plot of land, adjacent to the Croton Aqueduct. The house was likely similar in scale to those that Fowler promoted, with a modest porch and cupola. An 1868 map of Irvington shows the Armour house clearly represented as an octagon. Amour had already died in 1866, but his widow Rebecca retained the house until 1872 when a deed shows she sold the property to Joseph Stiner.

Joseph and Hannah Stiner are credited with the transformation of the dwelling, but how much of the design was their inspiration or a collaboration with an architect, designer, or builder is a mystery. In addition to their contacts in the city, the couple also would have had access to the rich network of skilled craftspeople in Irvington and the Hudson Valley and perhaps also gained some inspiration from printed volumes of the era.

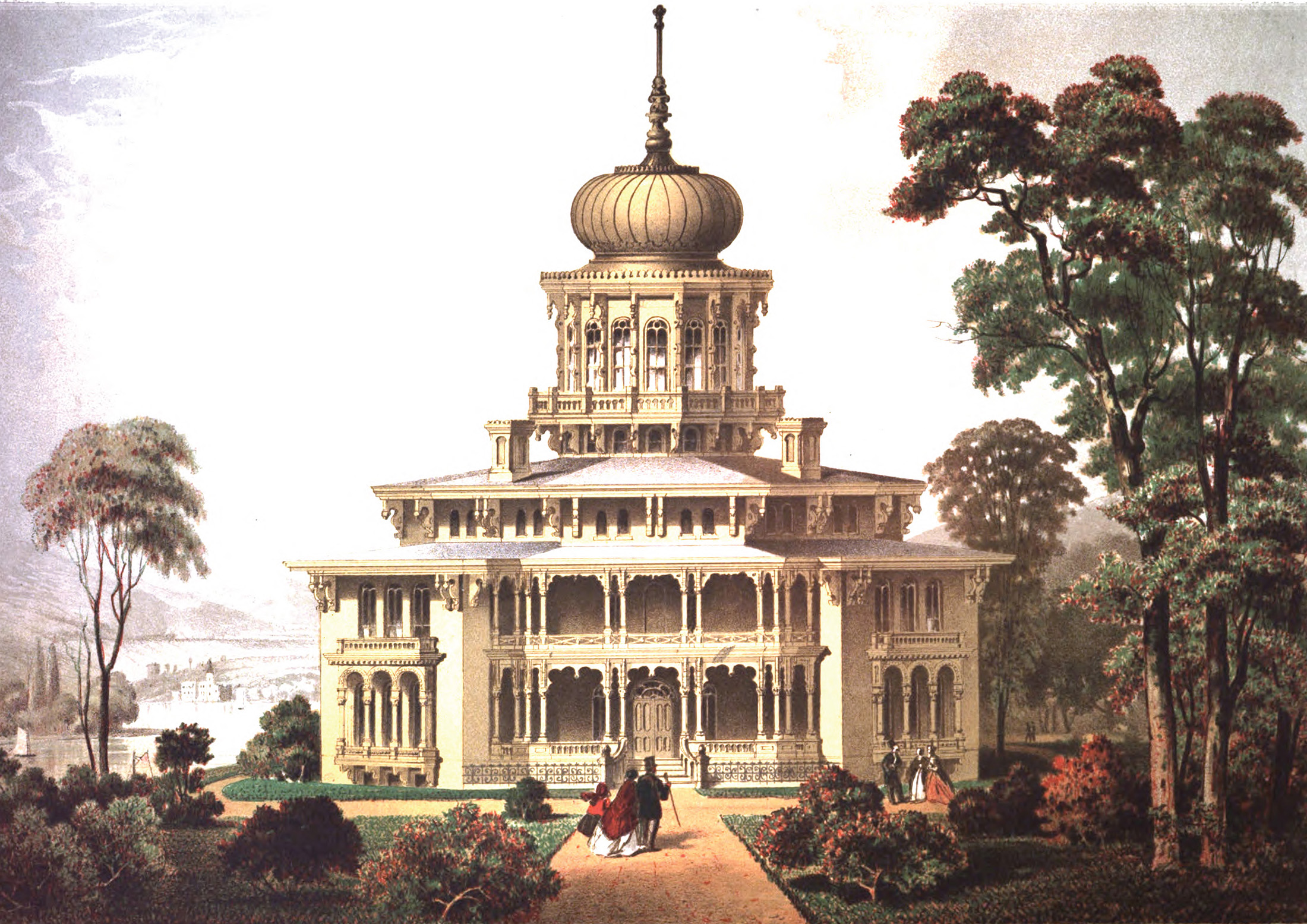

In addition to Fowler’s ode to the octagon, in the 1860s and 1870s an increasing number of builder’s guides and pattern books were available to advise potential homeowners on the latest styles and building techniques. Some of those books also included plans for Fowler-inspired octagon houses, but taken to the extreme with more ornate cupolas and layers of ornament. One particularly lavish octagon house was actually constructed.

In 1852 Samual Sloan published a plan for an “Oriental Villa” that included a spectacular cupola and onion dome atop an octagon dwelling. In 1860 Haller Nutt hired Sloan to construct a home based on these plans on his property near Natchez, Mississippi. While work began on the elaborate dwelling, including production of brick by the enslaved workers on site, it was interrupted by the outbreak of the Civil War. The unfinished mansion, known as Longwood or Nutt’s Folly, still stands and is open to the public.

While clearly a different design than what would emerge more than a decade later in Irvington, it presents an interesting comparison in the evolution of the ornate octagon style. Both have prominent columned porches as well as domes and cupolas. At Longwood, the emphasis is on a substantial cupola topped with a petite onion dome while at Armour-Stiner those proportions are flipped.

The Stiners’ architectural vision married the octagon form with a classically-inspired dome and added a healthy dose of Second Empire exuberance.

So exactly when and how did this architectural curiosity emerge in Irvington?

Digging into local papers of the period is usually a great way to turn up gossipy blurbs about houses under construction or recently completed. A deep dive did turn up detail-filled articles about other Irvington residences, including neighboring houses that can be spotted on a town map of 1875, like homes for David Dows and Cyrus W. Field. Those articles give insight into the decorative painting firms, architects, builders, and carpenters living in and around Irvington.

However, for such a distinctive house, the remodeling of the octagon doesn’t appear to have gotten a similar detailed treatment in local papers. New York City papers and periodicals, particularly the Jewish community newspapers of the period, do mention Joseph and Hannah Stiner, but the stories are focused more on the family’s life in the city, their Midtown home, art collecting, and charitable work, not the full details of their country retreat.

The deep dive into local history did turn up at least a few tantalizing mentions.

In July of 1872, the Evening Telegram noted that the Stiner family was “rusticating in their Clinton Avenue villa in Irvington on the Hudson.” The deed between Rebecca Armour and Joseph Stiner is dated May 31, 1872, so presumably the family spent their first summer in the house without making many major changes to the original, more modest octagon.

The next spring, two papers have very similar blurbs in their local gossip sections for Irvington, remarking that Mr. Joseph Stiner was remodeling the house he purchased from Paul Armour. One article notes Stiner is having it “fixed up in grand style” while the other just refers to “extensive alterations” to the house and the grounds. Unfortunately, they don’t go into further detail about what exactly those changes entail.

Work apparently continued on the property when the family wasn’t in residence. In February of 1878 the Yonkers Statesman remarked that a recent addition to the Clinton Avenue property was “a notable improvement.” Again, the notice is frustratingly short, with no detail on the work. However, it is possible that this was a reference to the completed dome.

Dating the Stiner renovations of the house to 1872 to 1878 seems to be confirmed by what appears to be the first mention of the dome in an edition of “Hudson River by Daylight,” a sightseers guide for those traveling up the river. The first edition appeared in 1872 and it was updated and reissued multiple times. It isn’t until a circa 1880 printing that a blurb for Irvington includes the note, “Joseph Stiner’s residence is easily distinguished by its large dome.”

The completion of the house may have coincided with some financial turmoil for the Stiner family. A real estate investment Joseph Stiner and some partners made in northern Manhattan doesn’t appear to have panned out, creating money troubles for the family. In detailing all of Stiner’s assets in 1878, the New York Daily Herald makes a rare mention of the Irvington residence, stating that “his wife owns a handsome house and grounds at Irvington.” Even that investment, which he purchased for $80,000 according to the paper, took a hit in the financial climate of the 1870s. The paper reported the house was now valued at only $40,000 and was mortgaged for $12,000.

Hannah Stiner died in January of 1881 and by May of that year the Irvington house was sold. The sale does seem to mark the first time the shape of the house rated a mention in local papers. Described as “the curious octagon house on Clinton Avenue, near Broadway, in Irvington” and as built by “one of the Stiners,” it sold for $30,000. That price, the paper noted, seemed a good one as the dwelling was on a small parcel of land.

It is after the sale from the Stiners to Susie H. Dibble and husband George that the octagon was photographed for the first time. The photo from circa 1882 shows a gentleman, possibly George, seated in a carriage in front of the dwelling. It is clear enough to see all the details in place.

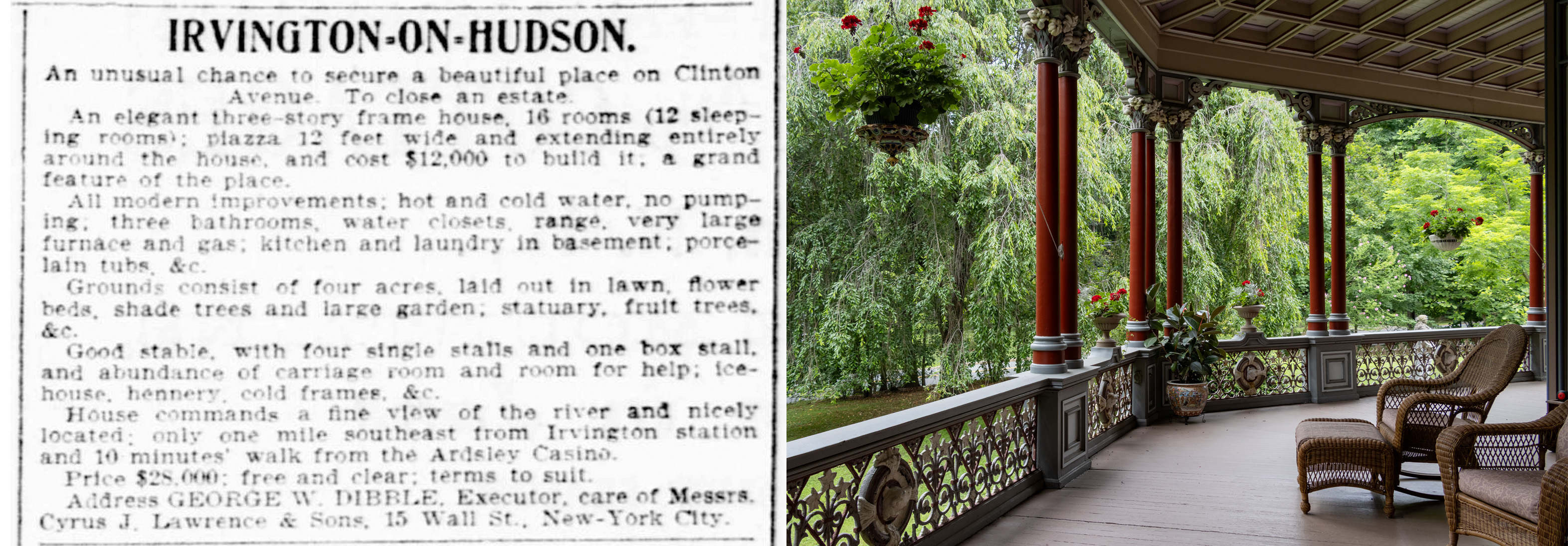

The first truly detailed description of the house appears to be in a sale ad first published in 1900 and repeated for the next two years. After Susie H. Dibble’s death in 1897, George, acting as her executor, put the house on the market and paid for the extensive ad.

The sales pitch touted the sale as “an unusual chance to secure a beautiful place on Clinton Avenue” and noted the dwelling was a three-story frame house with a 12-foot-wide piazza. The latter was described as extending “entirely around the house and cost $12,000 to build,” making it a remarkable feature of the dwelling. The house had modern amenities, including plumbing, water closets, and laundry. Features of the landscape included statuary, fruit trees, and flower beds. A “good stable” had room for horses and “help.” Other outbuildings included an icehouse and chicken coop. Interestingly, there isn’t any reference to the look of the house itself, beyond the piazza, which had Hudson River views.

Ultimately, whoever was responsible for the final look of the house crafted a complex exterior with fine attention to detail in all of that excessive ornamentation. Several themes are repeated, including maples leaves, which are found in the iron railing and the scrollwork of the porch and at the very top of the house in the fretwork adorning the cupola. Pattern books of the period certainly show examples to inspire the ornamentation of a house, including brackets, columns, and dormers, but the ironwork of the porch is a rather more idiosyncratic detail.

Adorning the center of every ironwork ornamental panel on the porch railing is the profile of a dog, bearing a collar marked “Prince.” It is believed to be a memorial to Stiner’s White English Terrier and likely based on an 1850s portrait by artist George Earl. However, by the time the Stiner family was in residence in Irvington, there was a new Prince in the family. Stiner, a dog enthusiast, showed Prince the greyhound, a “splendid creature” according to Harper’s Weekly, at the 1880 Westminster Kennel Club show.

Perhaps Prince the greyhound once roamed the grounds of the Armour-Stiner house. The landscape has matured since his time, with large trees now hiding the Hudson River views. The grounds did not escape attention during the restoration process. Work included a root analysis to determine what once grew there. Appropriate trees, including a striking Kentucky Coffee tree in front of the house, were added as well as an eight-sided formal garden.

Most of the outbuildings were destroyed by fire around the 1940s so a picturesque carriage barn and tool shed were built on the property as part of the restoration. Excavations showed where a greenhouse once stood. A Lord & Burnham greenhouse from the period was finally found in Pennsylvania and reconstructed on site.

For those who want to see the striking house in person, tours are available year round and there are special seasonal ones and events. Each summer the work of regional artists is featured in some of the upper rooms of the house. The grounds are open only to ticketed visitors. For full details on current tour offerings, visit the tour page online.

If you can’t visit in person, there is a digital guide to the house available on Bloomberg Connects, a free culture app.

More images of the interior and exterior of the house can be seen below.

[Photos by Susan De Vries unless noted otherwise]

Related Stories

- A Photo Tour of Troy’s Architectural Delights

- Lyndhurst Show Highlights Design Impact of Alexander Jackson Davis

- Manse Near Newburgh With Architectural Pedigree, River Views Asks $2.275 Million

Email tips@brownstoner.com with further comments, questions or tips. Follow Brownstoner on X and Instagram, and like us on Facebook.

What's Your Take? Leave a Comment