How the Victorians Brought Texture and Pattern to Walls

Hard-wearing inventions of the 19th century, Lincrusta and Anaglypta could be made to resemble leather, plaster, and other materials.

Installed in 1884, painted and gilded Lincrusta designed by Christopher Dresser decorated the frieze in the Rockefeller mansion dining room in Manhattan. Photo via Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum

Home decoration was all the rage in the late 19th century. With the Industrial Revolution in England and America in full swing, a growing middle class on both sides of the Atlantic had spending money and wanted to have the look of the expensive decor of the rich, as seen in shops and described in newspapers and magazines.

Advances in manufacturing technology made mass production possible and affordable. Most may not have been able to afford the best, but they could now buy lesser priced goods made to resemble those items. Silverplate instead of sterling silver, mass produced furniture instead of bespoke pieces, and affordable dishware patterned after expensive fine porcelain. Both kinds of goods were often produced by the same companies.

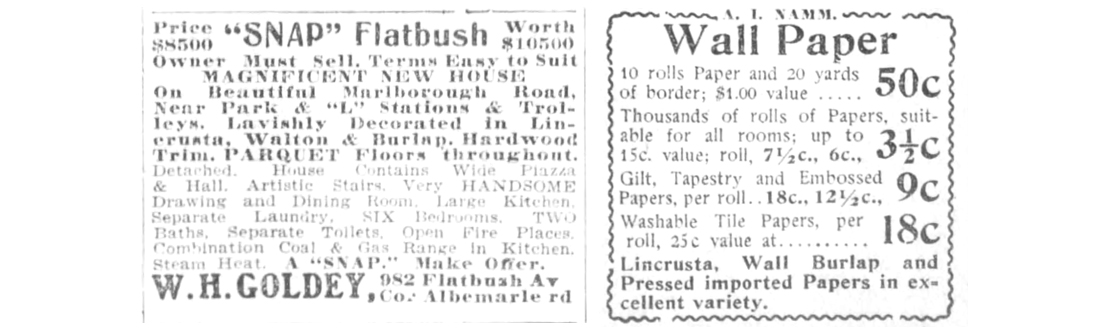

Wall coverings were also manufactured to appeal to this new demographic. Prior to the 19th century, fabric was adhered to walls as an expression of decorative elegance. Embossed leather was also popular in wealthy circles, especially in more masculine rooms such as a man’s study. But both fabric and leather were very expensive, even for those with money.

Block printed wallpaper followed, with many designs inspired by Chinese patterns of flowers and birds. By the beginning of the 19th century, the wallpaper found in the homes of the wealthy was hand painted or hand blocked, an expensive procedure making the cost far beyond most people’s budgets.

The Industrial Revolution brought with it great advances in printing, which helped make different grades of wallpaper affordable to almost everyone. Taking their cues from fabric printing, manufacturers began machine printing paper by passing it through a series of ink-fed rollers that transferred the patterns to the paper. The printing presses were powered by steam and could produce heretofore unheard-of feet of wallpaper quickly.

By 1860, Englishman Frederick Walton had already made a name for himself with his patent for linoleum floor coverings, an alternative to carpets. In 1877, he turned his attention to wall coverings, seeking to create a product that could replace expensive decorative plasterwork. His new process could produce wall coverings that were indistinguishable from plaster and also paint friendly. He called it Linoleum Muralis, but that name was soon changed to Lincrusta, derived from “lin” (linseed oil) and “crusta” (Latin for “relief”) His name was added to the product to identify it as the original: Lincrusta Walton.

Walton’s product was made from a paste of gelled linseed oil and wood flour spread onto a linen base. The material was then rolled between steel rollers, one having the pattern on it, thereby embossing the design on the material. The linseed oil continues to dry for several years, so the surface gets harder over time. It’s tough stuff, which is why so much of it has survived to this day. It’s not uncommon to find Lincrusta in many foyers and hallways in older parts of Brooklyn.

Lincrusta Walton was advertised as washable and paintable, making it extremely versatile as well as practical. Wall coverings were available for every part of a well-appointed wall: frieze, dado, and field. They could be painted white or any other color, and decorative glazing, aging, and other techniques could make Lincrusta appear to be leather, gilded plaster, and more.

Walton had a huge hit on his hands. In 1880 he opened a second factory in France. He introduced his products to America in 1883, where his patent was purchased by manufacturer FR Beck’s company, allowing Beck to legitimately manufacture Lincrusta Walton in the United States. In no time, Lincrusta could be found in row houses and mansions, hotel foyers, restaurants, and banks. It was even in the White House. Its washability and versatility were valued, and the elegant patterns were an important feature in the late Victorian decorative aesthetic of pattern, texture, and color on every imaginable surface.

One of Walton’s employees was John Palmer. He noted that as versatile as Lincrusta was, it was stiff and rigid and sometimes hard to work with. He came up with a product that was lighter and more flexible, a mixture of wood pulp and cotton. His embossed papers were better suited for large spaces like walls and halls and had the same paintable surface as Lincrusta.

He called his product “Anaglypta,” from the Greek “ana” (raised) and “glypta” (cameo). He was still with Walton at the time and offered the manufacturer the opportunity to make and market the product, but Walton saw it as a threat to his Lincrusta and turned him down. Palmer patented his product and then left the company to start his own business. He first exhibited Anaglypta at the 1887 Manchester Exhibition. It too was a great success, and by 1894 he had to move to a much larger space for his 100-plus employees.

In England, the two companies came together under one roof in 1931 and are both still in business today thanks to a new generation interested in period details. They still print many of their original designs. Over the decades they’ve kept up with changing trends and offer many new modern geometric and organic patterns for both lines.

If you choose to install new Lincrusta, or repair the old, it is recommended that an experienced Lincrusta installer work with it. The thick material requires a special adhesive as well as careful application. Many other companies now produce embossed paintable wallpapers, some available at big box home stores, but nothing beats the original texture and patterns. Invented as a lower cost alternative to plasterwork and leather, Lincrusta and Anaglypta are still popular with those who love and restore old homes or want a unique textured surface on the walls of their modern apartments and houses.

Related Stories

- What Was the Turkish Corner?

- The Story of Fretwork

- Albert Korber and the Business of the Artful Home

Email tips@brownstoner.com with further comments, questions or tips. Follow Brownstoner on X and Instagram, and like us on Facebook.

What's Your Take? Leave a Comment