Restoration of Grand Army Plaza Arch Gives Public Access to the Evocative Interior

The exterior revamp may elude most passersby, but interior work means the long-closed space can be safely opened for tours.

While the arch was encased in scaffolding for several years, the restoration work on the exterior was designed to be undetectable once it was uncovered. Photo by Susan De Vries

An iconic bit of Brooklyn has gotten a subtle polish with the completion of a multi-million dollar restoration of the Soldiers’ and Sailors’ Memorial Arch in Grand Army Plaza.

The restoration of the granite exterior of the monumental arch may be too elusive for most passersby to even notice, but work on the interior means the once closed-off space can be safely opened for occasional tours.

The official ribbon cutting took place on June 5, but Brownstoner recently got a behind-the-scenes tour focused on some of the restoration technology used to ensure the future of the memorial.

Dedicated to those who fought for the Union during the Civil War, the triumphal arch was designed by architect John H. Duncan in 1888. Construction began in 1889 and it was dedicated in 1892, but the arch wasn’t fully complete until the final sculptures were put in place in 1901.

The arch has previously been restored, but there is scant documentation of the original construction details or a 1953 revamp that included adding structural steel. The Prospect Park Alliance, which oversaw the restoration, turned to a high tech investigative technique for the first time on this project. A highly detailed scan provided valuable information on the existing structure and informed the decisions on where new interventions were placed.

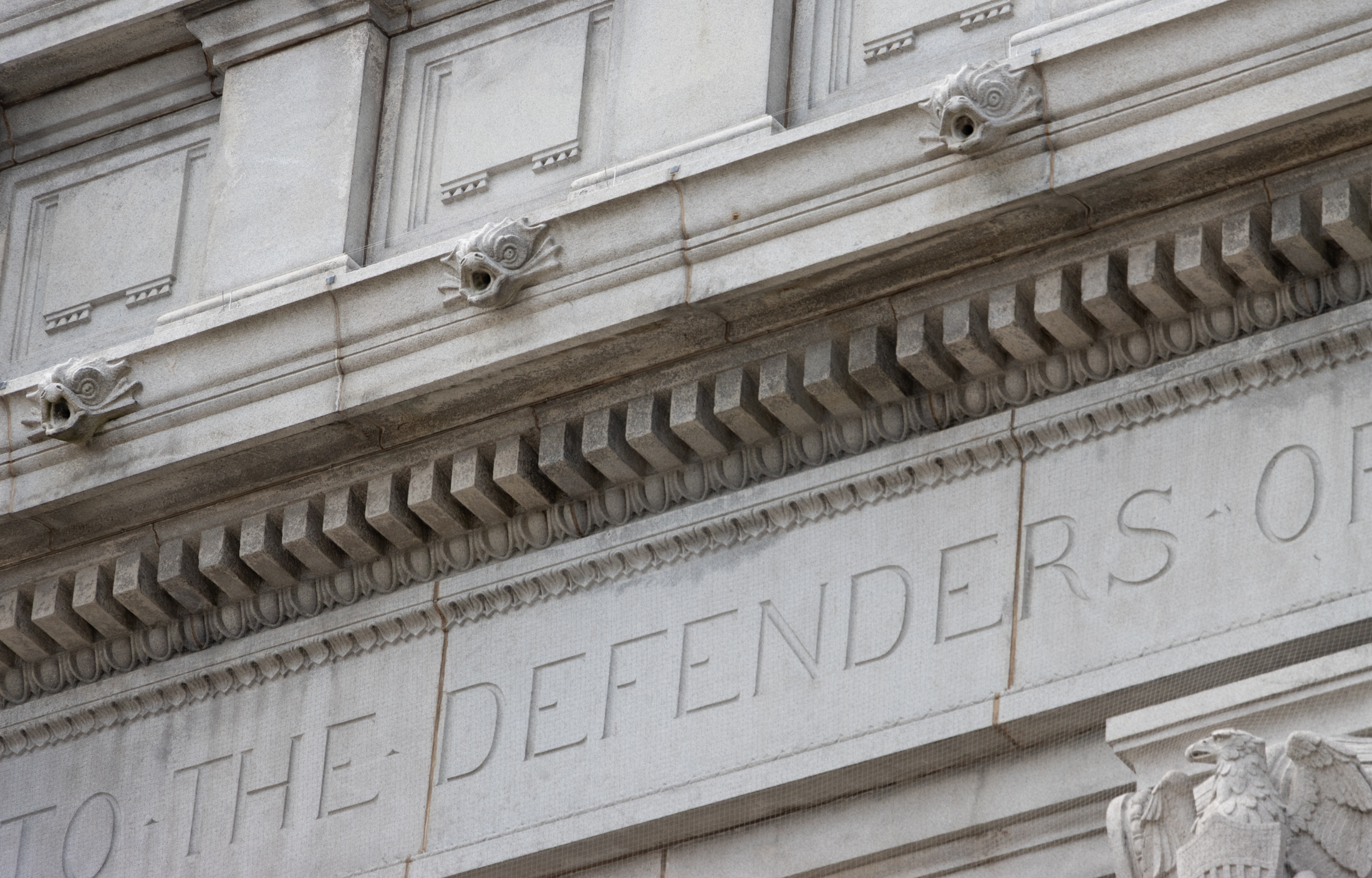

While the arch was encased in scaffolding for several years, the restoration work on the exterior was designed to be undetectable once it was uncovered. The entire surface was cleaned using a micro abrasion process, which uses a pressure wash combined with aggregate. Test patches on the granite ensured that the right balance of aggregate and pressure was determined before the entire surface was cleaned.

Every joint on the exterior was also repointed. Chemical analysis revealed the original mortar mix and it was replicated for the restoration.

The toll of water seeping into the structure over the centuries also had to be addressed. Water infiltration had left the plaster finish on the interior brick walls peeling off in sheets, iron staircases barely clinging to the walls, and a water-logged roof.

The architect behind the original design did include a gutter system with small grotesques acting as scuppers to shed the water. However, water infiltration seems to have been an issue almost from the beginning. Already in 1896, the Parks Department was reporting that the roof was “in exceedingly leaky condition” and repairs were needed.

“At the arch, the upper cornice acts basically as a gutter,” David Yum, director of architecture and preservation for the Prospect Park Alliance, told Brownstoner. “The original 19th century neo Classical design relied on scuppers to drain the flat roof, but today we know today this is not the most effective solution.”

During the most recent overhaul, multiple solutions were put into place to deal with the flow of water. On the interior, a new drainage system was installed. The network of pipes bring water directly down into Brooklyn’s storm water system. Sensors can detect if the pipes ever get close to freezing and can send a bit of heat through the system. New skylights on the roof also include a ventilation system, a sophisticated version of an attic ventilation fan that is automatically triggered by the temperature and humidity on the interior.

Before those skylights could be put into place, the waterlogged roof needed to be addressed. Making sure the roof had the opportunity to properly dry out after some 20th century repair layers were removed required patience and added to the amount of time the arch was hidden from view.

Another part of the interior work actually took place off site. Iron staircases spiral up each pier of the arch to a room, originally intended as a trophy or banner room, and ultimately to the roof. One of the staircases was in such poor condition that the lower half was removed, tagged, and sent off site for restoration. Layers of black paint were removed during that process, revealing newel posts with decorative brass trim. The pieces were reinstalled and the full staircase is now accessible and solid.

LED lighting strips now curve up the staircase, highlighting the structure while providing safety lighting. The same lighting has been used in the trophy room where it highlights the three original skylights designed by Duncan.

Whether that trophy room was ever actually used as intended has been one of the mysteries of the arch, but the arch was always intended to be a memorial and not a fully public building. It was one of numerous memorials constructed in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Brooklyn was not the first to boast a memorial arch dubbed a Soldiers’ and Sailors’ Memorial. In 1886, a sandstone arch of a medieval, rather than Classical, design was dedicated in Hartford.

The roots of the Brooklyn arch also date to the 1880s when the idea of the memorial was first floated. Eventually, a competition was launched in 1888 for a memorial in the form of an arch to be placed at the plaza entrance to Prospect Park. Over 30 designs were submitted for consideration, including some from Brooklyn’s notable architects like Rudolph L. Daus, Richard M. Upjohn, and the Parfitt Brothers. The entries were displayed in Brooklyn’s City Hall that year, but it wasn’t until August 1889 that the winner was unveiled.

Dramatically, the winning design was one that had remained completely anonymous, marked only with a red seal. It was accompanied by an envelope with instructions that it only be opened after the decision was made. The envelope revealed that the winning design was not by a Brooklyn architect, as suspected according to the Brooklyn Daily Eagle, but by the Manhattan-based John H. Duncan.

Some of the design elements, and even the exact placement of the arch, would be debated before construction began, but a sketch of the proposed arch published in 1889 shows that Duncan planned for sculptural pieces as a feature of the design. Duncan chatted with a Brooklyn Daily Eagle reporter in August of 1889 about some of the back and forth, saying he agreed with some suggested changes including “doing away with a group of figures at the top of the monument” in favor of a parapet adorned by eagles.

The cornerstone was laid in October of 1889 with great ceremony and work commenced. While some of the larger sculptural pieces were not yet installed, a dedication for the arch took place in October of 1892 as part of a larger celebration of Christopher Columbus.

Brooklyn-born sculptor Frederick MacMonnies, who was living in Paris, was awarded the contract for the sculpture in 1894 and, apparently in a reversal, this included a massive piece for the top of the arch, the quadriga of Columbia. It was installed in 1898, blocking one of the original Duncan skylights and adding significant weight to the structure. It was the shocking fall of a portion of the quadriga in the 1970s and the deterioration of the park that spurred the creation of the Prospect Park Alliance in 1987.

In 1901 the final two sculptures, groups representing the Army and the Navy, were hoisted into place.

The original call for entries to the competition specified that the plans for the memorial arch should include a room that could be used for the exhibit of war-related objects. Duncan himself, when interviewed by the Brooklyn Eagle, described his plan as including stairways in each pier leading to rooms for displaying relics as well as a long hall at the top of the monument.

At the time of the dedication in 1892, at least one newspaper account described plans for the banner hall to be rather finely finished. Walls were to be decorated with marble wainscoting, mosaic panels, and “ornamental work commemorating the heroes.” In 1898, a few years after the arch was dedicated, the space still hadn’t been fitted out as a museum with the Brooklyn Daily Times reporting that it it didn’t look like anything was likely to happen.

While the arch was used for art installations and storage in the 20th century, the trophy room appears to never have been used for its intended purpose. Restoration work on the interior seems to confirm this, showing the only elements that were completed for the space were the three skylights and ornamental ironwork above doorways.

Post restoration, the arch isn’t open to the public at all times, but the work has made it possible for the curious to see the interior. The Urban Park Rangers will be offering monthly tours of the exterior and interior, weather permitting. While visitors won’t be able to get out and see the spectacular view from the roof, they will be able to ascend the stair and get a look inside the trophy room. Space on the tours will be given out by lottery. Available tour dates will be updated at the NYC Parks calendar online.

For those who happen to wander by the arch at night, the new lighting system is still being tweaked to get the correct placement and light levels. The lighting, landscaping around the plaza, and restoration of paving around the nearby Baily Fountain were all part of the project, which received $8.9 million in mayoral funding.

[Photos by Susan De Vries unless noted otherwise]

Related Stories

- A Colorful Shelter Returns With the Restoration of Prospect Park’s Concert Grove Pavilion

- A Delightfully Striped Interior Returns to Prospect Park’s Endale Arch

- The Grand Army Plaza Soldiers’ and Sailors’ Memorial Arch Lights Up the Night

Email tips@brownstoner.com with further comments, questions or tips. Follow Brownstoner on X and Instagram, and like us on Facebook.

What's Your Take? Leave a Comment