The Story of Fretwork

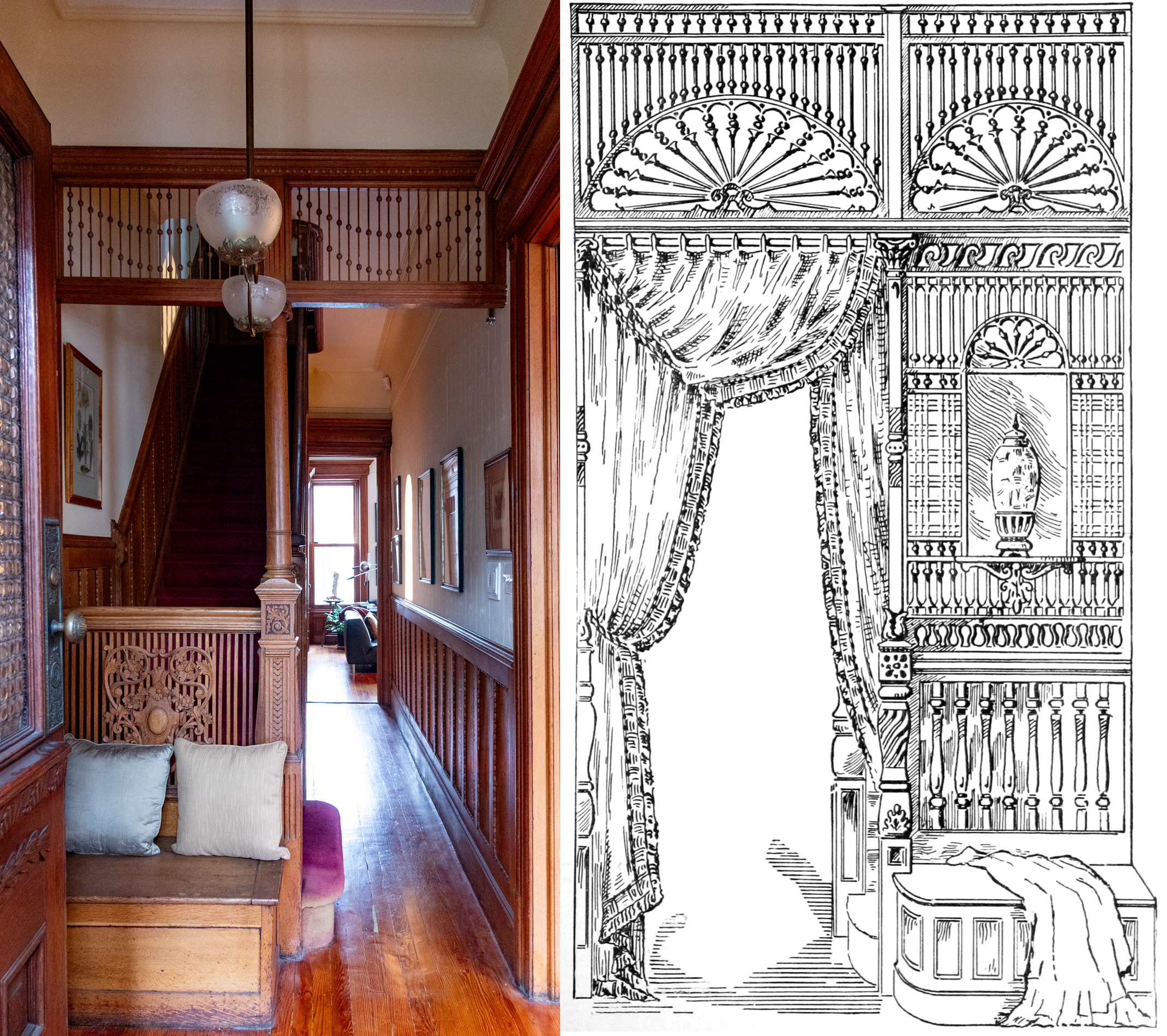

An example of late 19th century elegance, fretwork screens beautified transitions in entries, parlors, and bedrooms.

In Bed Stuy, scrolls and wheels demarcate a bedroom and pass-through. Photo by Susan De Vries.

The architecture and decorative arts of the late 19th century were greatly influenced by the Aesthetic Movement, which began in the 1870s. It was the beginning of an age of ornament and beauty for beauty’s sake that was constantly added to and modified until the end of the Art Deco period.

Exterior and interior decorative elements were important features that became standard in the residential architecture of the day. The design motifs of exotic foreign lands were eagerly modified to fit contemporary homes, with Japanese and Middle Eastern motifs the most popular.

The Gothic Revival period introduced the exterior wooden ornaments we call “gingerbread.” It was used extensively in mid-19th century residential architecture, especially in patterned bargeboards in gables and in the elements making up porches. Gingerbread became more elaborate later in the century thanks to mechanization and changing styles. Sharing the same vocabulary and production methods, interior woodwork also grew in complexity and importance.

This included fretwork, which gets its name from the French word “freter,” or lattice. It’s an expanse of decorative and often delicate open woodwork held together by a wood border. Its mass production and widespread use in the late 19th century was made possible by machines.

Its design elements can be broken down into at least three distinct styles or types, with a great deal of fretwork incorporating a combination of all three.

The archetypical one is ball and stick, a combination of wooden balls connected to each other by varying lengths of dowels. A design could be as simple as a solid panel of identical balls and sticks mounted within a frame — or more complicated pieces with inventive combinations of size and configuration. One of the most popular motifs was a fan design, often used as a center element or in a spandrel. The latter was a curved piece that acted as a bracket on the sides of a larger panel, creating an arch.

A second approach features floral or other designs cut with a scroll saw, the industrialized version of a fret saw, a hand tool with a narrow horizontally mounted blade that can navigate curves and tight spaces. These designs generally feature center or spaced elements with mirrored floral or geometric designs extending on both sides to the borders of the piece. Spandrels and brackets were often a part of the design as well.

Depending on the style of the house and its price point, this work could be quite ornate and complicated, but most of our speculative brownstone housing featured simpler designs that could be easily mass produced. Many millwork companies sold their fretwork through catalogs. Every good architect of the day probably had several. Today, there are a few millwork companies who produce decorative woodwork, but they mostly specialize in exterior gingerbread.

The third fretwork type resembled woven wicker. It was called Moorish fretwork and its invention has been attributed to a Cleveland woodworker and furniture designer named Moses Younglove Ransom. He patented his techniques for creating and interlacing spiral wooden rods, and produced his first designs in 1885.

Ransom was working during the Aesthetic craze for all things from the Middle and Far East, which resulted in “Moorish” rooms. Based on romanticized paintings of harems, they featured divans and daybeds in dark corners with lots of large pillows, Moroccan lanterns, and a decorative hookah. Intricately carved wooden latticework known as mashrabiya and found everywhere in the Middle East was a must for these interior spaces and were his inspiration.

Ransom’s designs wove together a left-handed spiral rod and a right-handed one. The thin spiral rods could be mass manufactured using a machine Ransom invented that produced them in any length needed.

“My invention successfully brings within reach of people of ordinary means articles of great beauty and utility heretofore only attainable by the rich at great cost,” he wrote in his patent application, according to a story in the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette.

Moorish fretwork became very popular and was used by itself or with ball and stick and scrolled designs. It didn’t take long for manufacturers to mix all three together, producing some beautiful and amazing work. A designer was limited only by his or her imagination.

Most of our Brooklyn row houses from the late 19th century had some kind of fretwork on the parlor floor and often in a ground floor dining room. On the parlor level elaborate designs were used as room dividers between front and middle parlors or between parlors and the hall.

Many homes had dog-leg interior stairs with a small landing at the turn, and fretwork was often used as a screen on the landing, or it could frame the entire stairway, creating an arch from wall to wall. It’s not uncommon to see it on upper floors as well, where it might divide a bedroom from a pass-through dressing area with built-in closets and marble sinks.

Unfortunately, as the years went by, fretwork went out of favor. People wanted clean lines and modern spaces, and fretwork was also a pain to dust and keep clean after live-in servants were no longer there to do the work. The ball and stick work was especially prone to damage, and many people just couldn’t be bothered, and the panels came down and were either thrown out or cast into basements.

When all things Victorian came back into style during the brownstone revival of the late 20th century, surviving fretwork was cherished once again. More than one house was sold because of an elaborately festooned hallway with lots of varnished oak fretwork. Original fretwork can be found in architectural salvage or antique stores today. Mounted across doorways or on the wall as art, fretwork is a beautiful example of Victorian elegance.

Related Stories

- What You Need to Know About Reglazing a Sink

- Four Ways to Save Original Details and Character When Updating an Old House

- What Was the Pass-Through?

Email tips@brownstoner.com with further comments, questions or tips. Follow Brownstoner on X and Instagram, and like us on Facebook.

“ More than one house was sold because of an elaborately festooned hallway with lots of varnished oak fretwork”.

Ours is between the front and middle parlor, but was indeed one of the first things we noticed when we entered what would be our house, so it did indeed help make the sale.