Downtown Brooklyn’s Forgotten Emporiums

The Brooklyn Furniture Company was an advertising innovator of its day, and well-to-do Brooklynites bought entire wardrobes at Journeay & Burnham.

An illustration of shoppers in A&S in Downtown Brooklyn published in 1892. Image from Pictorial New York and Brooklyn via Library of Congress

There was a time when Downtown Brooklyn’s shopping district had anything and everything one would need for holiday giving, and just plain old year-round shopping. By the end of the 19th century, the area between Adams Street and Flatbush Avenue and its side streets were packed with shops large and small, theaters, restaurants, banks, and social amenities such the YMCA. There was nowhere in Manhattan or any other part of New York City that had this many stores and entertainment venues contained in one small area. Not 5th avenue or 34th Street.

Much has been written about the large department stores that were within what was called the “Dry Goods District,” as mapped out in the 1904 Sanborn insurance map of Brooklyn. Abraham & Straus, Frederick Loeser’s, A.D. Matthews, and Chapman & Co. Namm’s and Oppenheimer Collins came a bit later, as did Martin’s, which took over the Chapman space in the Offerman building.

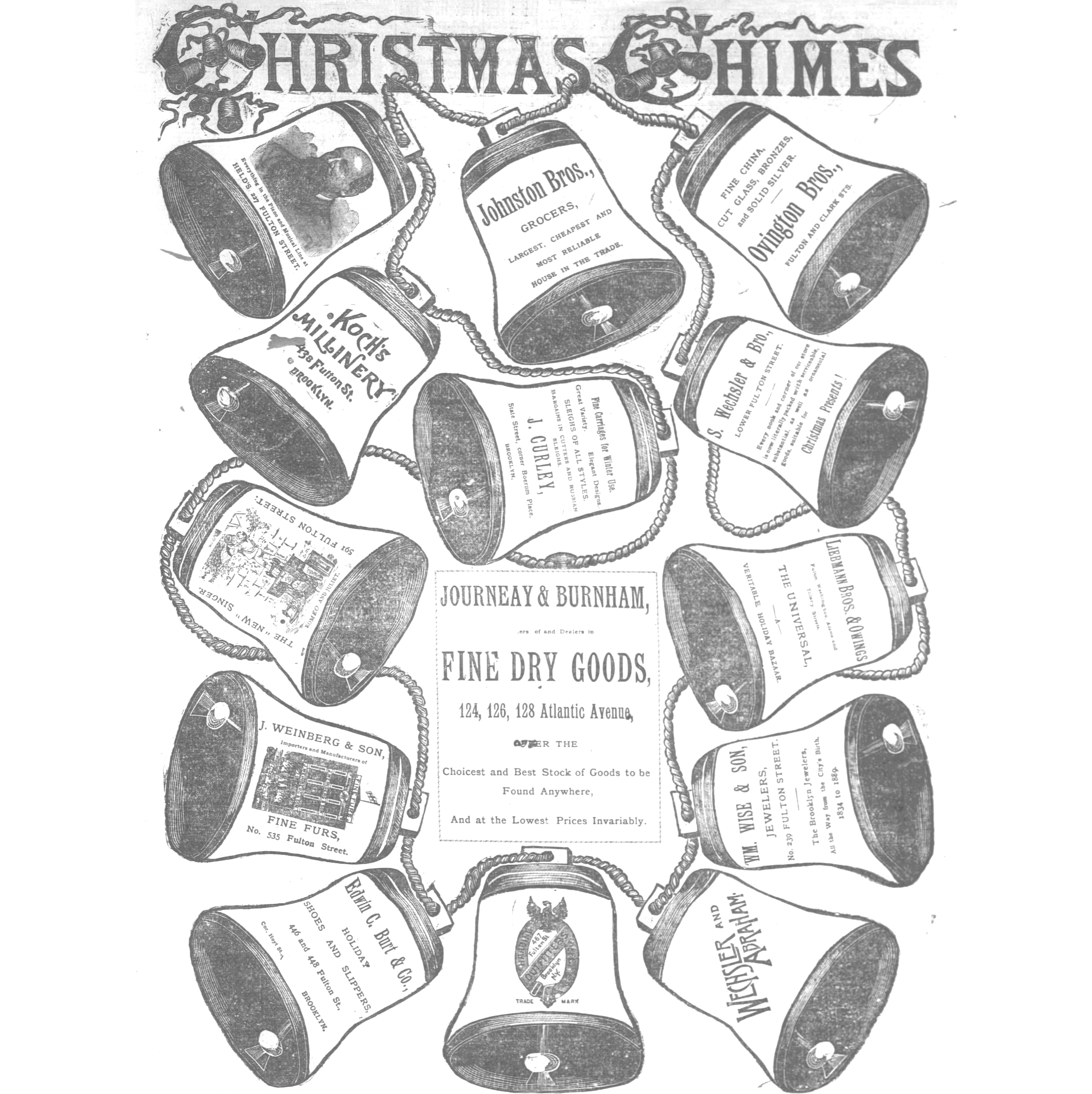

In between these behemoths were smaller stores. Many were specialty shops catering to a specific market. There were furriers, milliners, furniture, footwear, sports, jewelry, print, and stationery stores. There were separate shops for men, women, and children.

Most people aren’t aware of them now, but there were two specialty stores that had large customer bases and were masters of advertising, which means we have a record of their businesses and the wares they sold. Even a casual examination of sales ads of this period as posted in the Brooklyn dailies and other ephemera illustrate their success and popularity.

The Brooklyn Furniture Company

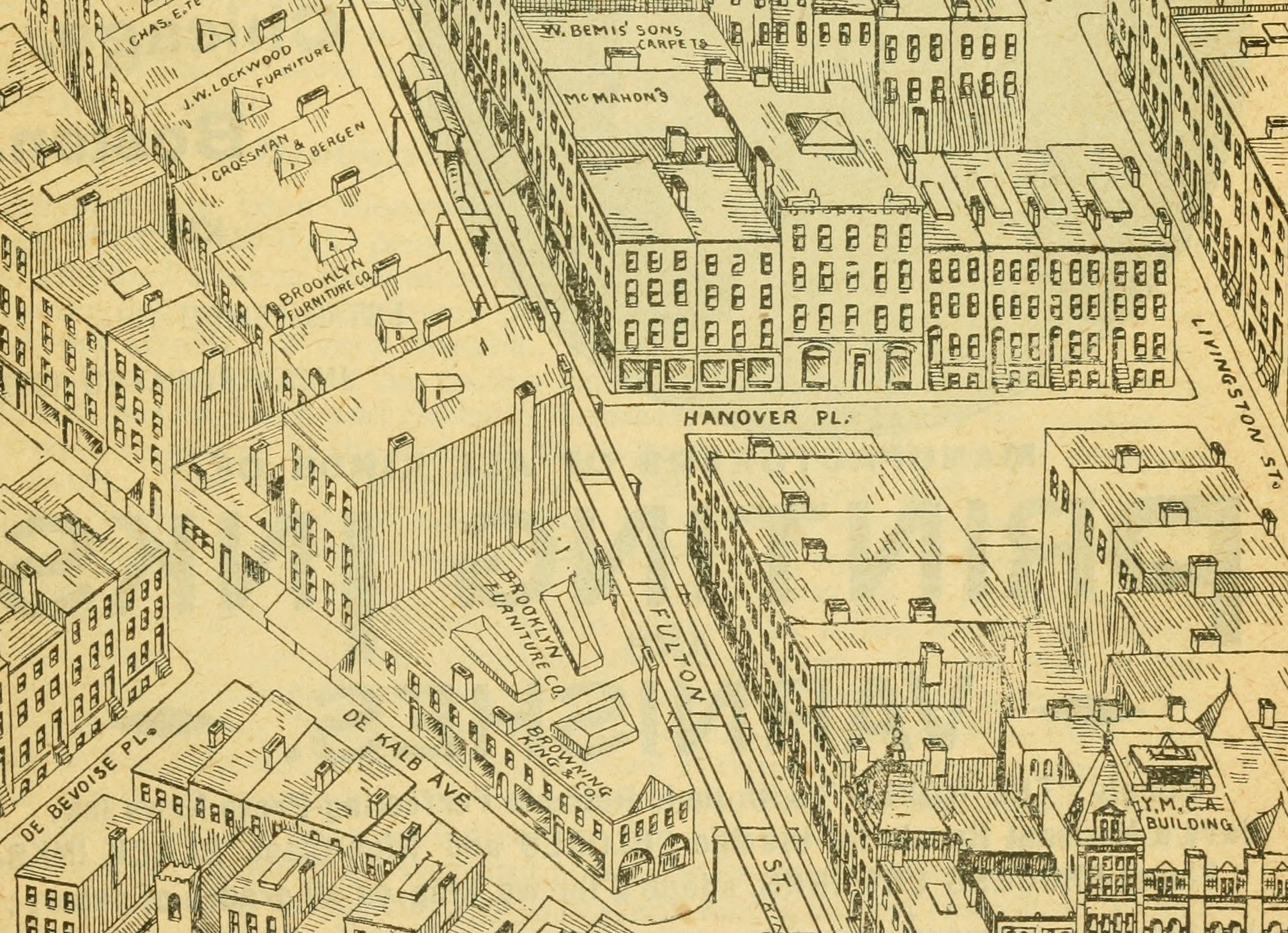

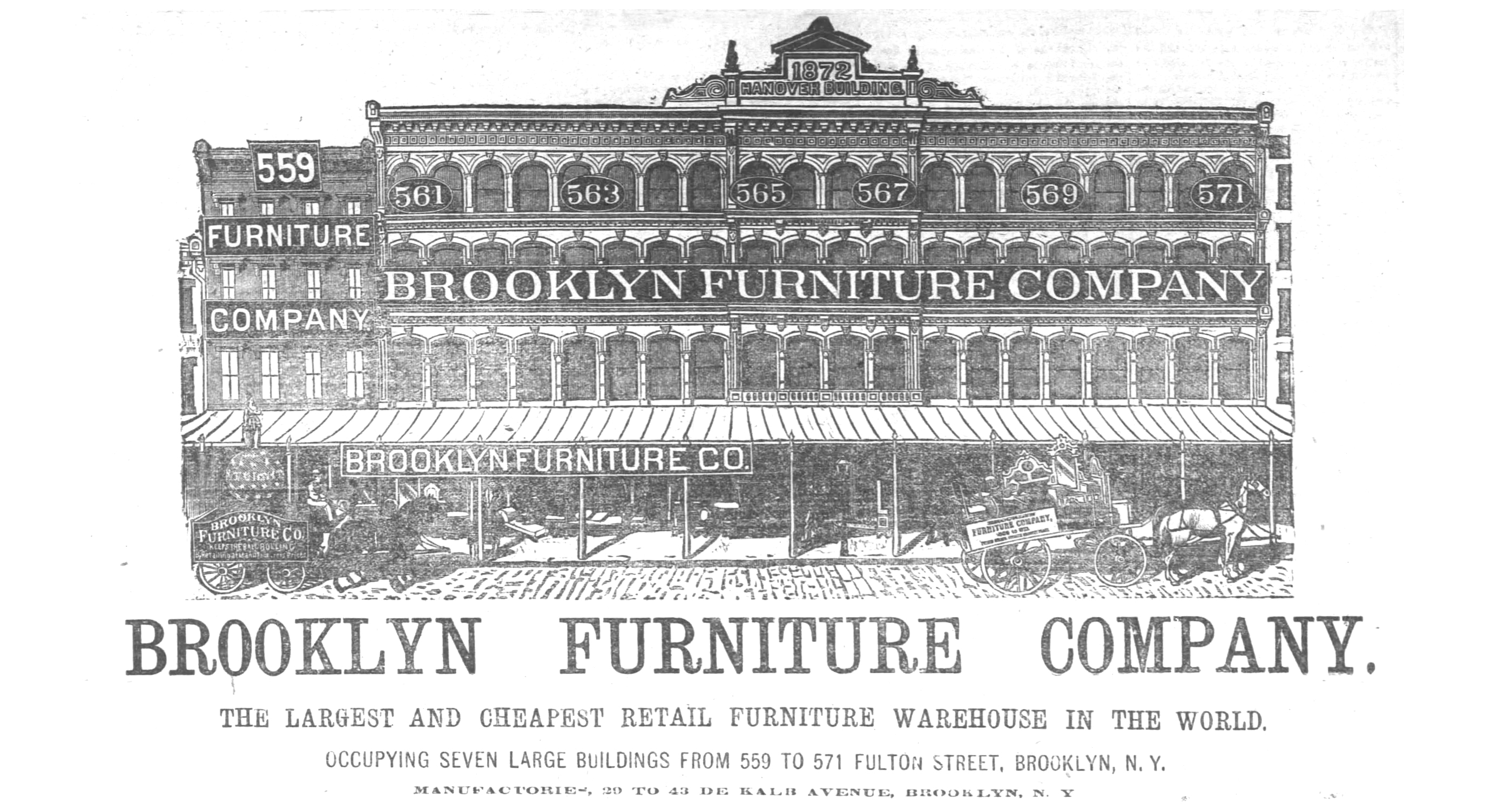

It didn’t have a fancy name, but the Brooklyn Furniture Company was an important member of the family of stores on Fulton Street. It was located on the north side of Fulton between Bond and Flatbush Avenue. It began with two storefronts but in the space of only a few years spread out to include seven lots, Nos. 559 through 571 Fulton Street — almost that entire short block.

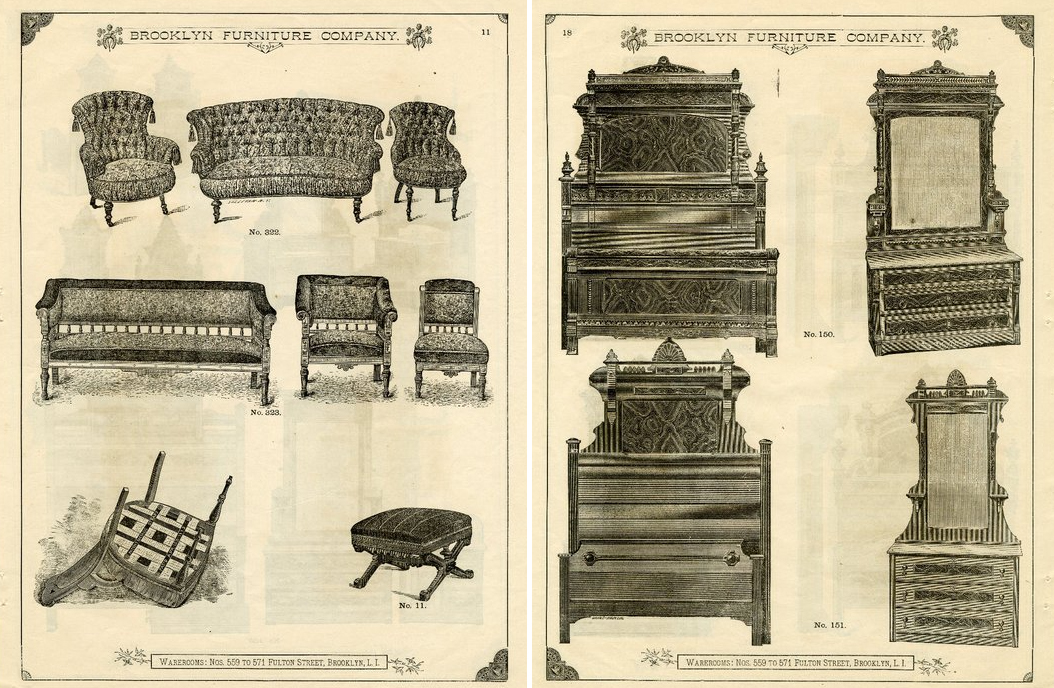

They manufactured some of their own products and carried the lines of three other companies. The furniture factory was located behind the retail store at 29-43 DeKalb Avenue. They made parlor furniture. A second factory at 113-121 Manhattan Avenue in Greenpoint manufactured bedroom furniture.

Mass-produced furniture was the result of new technology. In the past, the furniture most middle-class people had in their homes was handmade. Carpenters made pieces one at a time, milling and slicing timbers, turning wood, sawing, drilling, and planing the various components and putting them all together. Furniture was rarely discarded or switched out for trends, and many people had pieces that were handed down for several generations.

But in the latter part of the 1800s, it was possible to do all that with machines. For those of us today who prize Victorian-era furniture, unless your pieces are really high end, they most likely were products of a furniture factory. Planers, saws, drills, and lathes could all be run on steam power, which cut down on the hours needed to create a piece, and didn’t require a fine furniture carpenter.

Piecework, where an operator made only one part and others assembled and finished the pieces, made it possible for large quantities of goods to be manufactured quickly and inexpensively. Those savings could be passed down to the consumer, making furniture something that most people could afford to buy.

The Brooklyn Furniture Company was one of the oldest furniture manufacturing companies in Brooklyn. A. Pearson founded the business in 1870 at this location. The A. Pearson Company took on Isaac Mason as a partner in 1872, and they carried on until Mason bought Pearson out in 1875. Mason was already an old hand in the business; his father established his furniture business in Brooklyn in 1843. Mason learned the trade at his side.

By 1877, ads began to appear in the local papers announcing “Something New in Brooklyn – Brooklyn Furniture Company will occupy the store at 581 and 587 Fulton Street. The firm of A. Pearson & Co. having dissolved, the Company will offer furniture of all kinds as even lower prices than ever.”

This first short announcement was the beginning of a vigorous ad campaign that would define the store. Another 1877 announcement informed the public that the new business retained most of the employees of the old. They offered guarantees on their merchandise and a refund should it prove unsatisfactory. They thanked customers for past favors and hoped the public would continue to support the business. Isaac Mason was as good an ad man as he was a furniture manufacturer.

He paid for a regular column in the Brooklyn Eagle called Shavings. It began: “Read Shavings from the shops of the Brooklyn Furniture Company.” Then followed short tidbits of news and advertisements for various events and products, with a BFC ad in between each unrelated announcement. News might include a favorite hotel in Florida re-opening, followed by an ad for a burglar alarm, then something about the Brooklyn Furniture Company, repeated the length of the total column.

Mason didn’t just advertise his goods; he explained his business modus operandi. One ad in this first year of business began with “It is the first time in the history of the furniture business in Brooklyn that the manufacturers come directly before the customers and offer their goods with only one profit.” It went on to explain how that was possible and then touted the quality and various price points of their products, which could “adorn the parlors of our richest citizens as well as the unpretentious homes of the men of moderate means.”

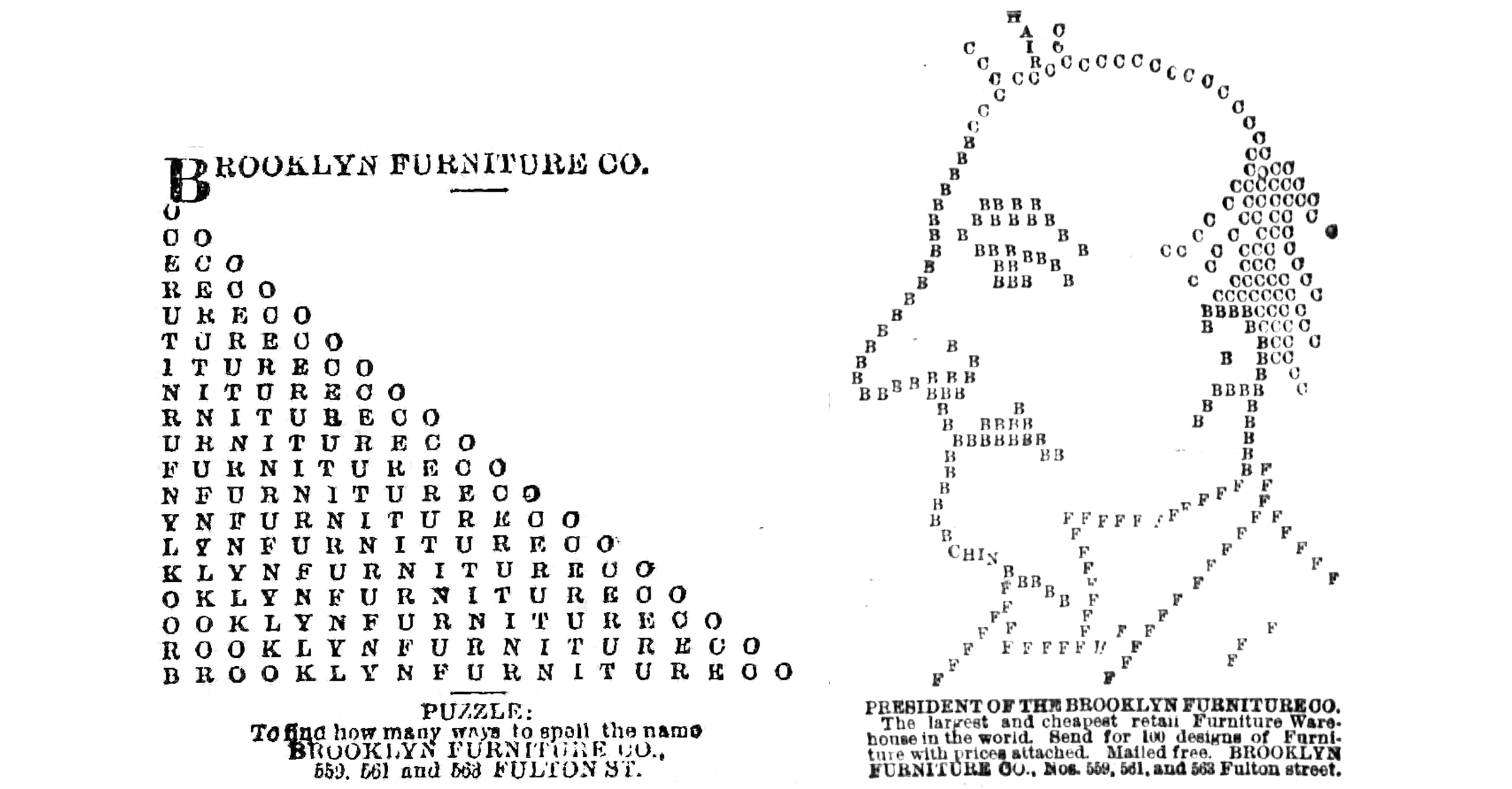

He also took advantage of a new graphic trend where single letters were spaced out and repeated to create abstract designs, puzzles, and images. The typesetter could create large designs by spelling out words such as Brooklyn Furniture Co., as well as surrounding them in a circle. This took time and was probably quite expensive. An ad published in 1878 showed a portrait of the firm’s founder created out of the letters making up the name of the Brooklyn Furniture Co.

At different times of the year, Brooklyn Furniture Co. held special events meant to draw in customers. The holiday season was a busy time for the company. Isaac Mason supported various charitable organizations, collecting money and toys and sponsoring events for disadvantaged children at Christmas. These events not only raised money, but they also brought people to his door where he hoped many would buy something.

Brooklyn Furniture didn’t just have showrooms of furniture. Carpets, bedding, oilcloths, room accessories, and more complemented the furniture and were available for purchase. At Christmas, they sold holiday decorations, novelties, and stocking stuffers.

For Christmas in 1881, Mason and his employees outdid themselves. The entire row of display windows facing Fulton Street was a stage set. Half the windows showed a nighttime scene with snowy countryside and a full-sized cottage. One side of the cottage was open, and a bedroom with a trundle bed, a cradle, and sleeping children could be seen. The back of the cottage had a chimney and a hearth with a flickering fire. Far away in the countryside part of the set, viewers could see Santa on his sleigh pulled by reindeer traveling down the winding road and getting closer, then disappearing from view.

The entire show was a complex mechanical wonder on a track, with no humans or animals. Then viewers saw a real sleigh and a real Santa pull up in front of the cottage. He walked through ankle-deep snow, hoisted his bag of toys on his back and climbed a ladder to the roof. Then he looked around before coming down the chimney and appearing in the children’s bedroom. He left dolls and toys for the children before going back up the chimney, over the roof, back into the sleigh and then disappearing off stage. The children on Fulton Street went wild, cheering and screaming.

The crowd for this show was so large that the police had to be called to maintain order. It started at 9 p.m., by which time men, women, and children crowded around the store, and those who couldn’t get close stood across the street. This was before the Fulton Street El train was built. The crowds grew so that the police had to clear a path so carriages and other vehicles could travel down the street. For that one hour, between 9 and 10 p.m., it seemed as if everyone in Brooklyn was there.

It turned out that Santa was a young man who worked for the business, made up so well that no one guessed he was a teenager. The Brooklyn Standard Union reporter who logged this story noted that “the youth is an excellent actor.” That wasn’t all. Every morning from 8 to 9 a.m., Santa was back, giving out a suite of cardboard furniture to every child. Over 1,200 sets were handed out that year. The reporter also gave a list of the merchandise in the store, noting that all would be “acceptable as Christmas gifts.”

In March 1879, Mason’s carpenters built a very large scale model of a three-story brownstone, complete with a mansard roof. Like an oversized classic dollhouse, the 12 furnished rooms opened to the viewer. Each was decorated according to its function, from the parlors to the bedrooms and servants’ rooms. There was even a billiard room on the mansard level. Functioning wash basins, a bathtub, lighting, and more completed the scene.

The gas fixtures in the house worked, and each evening the lights would be turned on, creating a perfect model of a fashionable house. All furniture, carpets, and furnishings were sold by Brooklyn Furniture Company, of course. It was called the “Midget House.” An ad in the paper invited visitors on guided tours of the house during the day and evening hours, free of charge. No doubt the store enjoyed the business of customers new and old.

Brooklyn Furniture’s windows were always attractive, perhaps too attractive. One evening in June 1881, a man named B.E. Taylor was standing in front of the store admiring the goods in the window when a thief picked his pocket, stealing his silver watch and gold chain. He could only report the theft at the local precinct house; he probably never even saw the perpetrator.

Employees of the Brooklyn Furniture Company enjoyed company outings, and the store sponsored an employee target shooting team. They had some fine marksmen in their employ and won several amateur prizes. With the Civil War only 10 years back, no doubt many of the employees had arms training. They often held events such as contests and celebrations at a place called Bennett’s Hotel in East New York, traveling by special private train car to get there.

Isaac Mason and many of the other store owners on the street were often asked about policies and events that directly affected their businesses. In 1884, a series of tariffs was instituted by the government. Fulton street owners were interviewed about whether they supported the tariffs and how they had impacted their trade. They were also asked about how their businesses were changed by the 1883 opening of the Brooklyn Bridge. The manager of the Brooklyn Furniture Company was enthusiastic, noting that increased competition from the other side of the river would show buyers the quality and bargain prices available to them from his business and Brooklyn establishments in general.

Isaac Mason remained with his company until 1912. He sold his interests then and retired. He died in 1917. In 1927 the business was purchased and then sold again to the firm C. Ludwig Baumann. They were a furniture chain with several branches in New York, including one branch already just down Fulton Street. Baumann planned to distribute Brooklyn Furniture’s warehouses of stock among all of his stores. He announced that he wanted all of it to be gone in 30 days regardless of cost or value. The Brooklyn Furniture Company was no more.

Journeay & Burnham

Decades before the Dry Goods District of Fulton Street became a shopping mecca, fashionable shoppers flocked to Journeay & Burnham on Atlantic Avenue. In 1844 Henry P. Journeay and Lyman S. Burnham established a small dry goods shop on Atlantic. Henry R. Stiles, whose 1884 book “The History of Kings County” is an invaluable chronicle of Brooklyn, wrote “They began in a small way, with one salesman and one boy, and now have over 200 employees. Their trade has always been confined to dry goods alone.” Seven years later, the shop moved to 124-128 Atlantic Avenue between Clinton and Henry streets. They were one of the pioneer dry goods stores in Brooklyn. (Dry goods are textiles and things made from them such as manufactured apparel and home goods.)

Both men had been in the dry goods business before, having worked for various merchants earlier in life. Opening Journeay & Burnham was a risk. But soon their reputation grew as shoppers found well-made and fashionable clothing, accessories, and fabrics there. One woman, reminiscing about her childhood in 19th century Brooklyn Heights in “Yesterdays on Brooklyn Heights” said, “Something quite unique in our community were the Saturday morning gatherings at Journeay & Burnham, the dry goods shop on Atlantic Avenue where all the ladies from Brooklyn Heights went with their shiny black shopping books, in which the week’s purchases were written up.”

Burnham was the face of the business. He was a genial host, comfortable with people and always ready with an item that would suit one of his customers. Journeay, a quiet man who preferred to tend to his business away from the crowds, tended to stay in the background. And what a business they had. Their growth was such that they moved several times on Atlantic Avenue, always expanding their business. In 1849 Hugh Boyd became a partner, although his name was never added to theirs. He remained with the company throughout its history.

The wealthy women who patronized the shop bought entire wardrobes there. There were other dry goods merchants (more were established in the years after the Civil War) but Journeay & Burnham were reliable sources for gowns, corsets, hats, parasols, and anything else a fashionable woman needed to promenade. When their store was located at 124-130 Atlantic Avenue, they had four floors of merchandise to choose from and still had to build an annex on Pacific Street. Today, that structure is called the Atlantic-Pacific Building and is a landmarked condominium.

Like everyone else, Journeay & Burnam advertised in the daily Brooklyn newspapers. As the years went by, they began expanding their wares, and offered not only fine silk, wool, and cotton fabrics, but also sold belt buckles, notions and ribbons, capes, coats, hats, French and Irish tabletop items, towels, runners, and bed linens.

Henry Journeay was quite eccentric. For some reason no one ever figured out, he and Burnham had a falling out, and Journeay didn’t speak to him for years. Burnham was also stubborn, so the freeze-out continued until Journeay got married, and the silence ended and they were fast friends for the rest of Journeay’s life. In 1890 he contracted a cold which never left him. It eventually went to his heart, and he died that year on Christmas Eve. He was 75. He was mourned by his family, friends, and people in the industry, who remembered him as a strange but genial man, plain spoken and unpretentious, and one of the best dry goods men of his day.

Burnham partner Hugh Boyd and others reorganized the company and incorporated. They had yearly profits well over a million dollars for more than 30 years, and their offerings of preferred and common stocks were backed by their credit history and reputation. The new board decided that the Atlantic Avenue location was still too small, and the avenue was no longer a popular shopping destination, as everyone had moved down to Fulton Street.

Ten years before they moved, Journeay & Burnham purchased 28 to 36 Flatbush Avenue near Fulton and Livingston streets. By 1892 their new four-story and basement emporium was completed. It was a grand building with 104 feet of frontage on Flatbush Avenue. The first two floors were clad in Ohio sandstone with carved ornamentation. Immense plate glass windows studded the first two floors, with light streaming into the interior from the Livingston Street side, as well.

The ceiling on the first floor was 17 feet high, supported by iron girders and pillars. The woodwork was oak and mahogany. Here hats and notions were sold such as ribbons and laces. This was a modern store with three electric elevators: two for passengers, one for freight. The store was lit by electric lights.

The second floor held muslin goods, cloaks and wraps, shawls, and flannel goods and cloths. The third floor was home to upholstery fabrics and hangings, and the fourth floor comprised a new feature for the company, a dressmaking studio with all the latest equipment, as well as the company offices. The new store opened on March 22, 1892.

Lyman Burnham died in 1897. He was 81. His many obituaries told of his childhood in Utica, New York, his early days in dry goods, and the success of Journeay & Burnham. He had numerous outside interests, and was a patron of the library, the Brooklyn Atheneum, and a founding member of the Philharmonic Society. He was also a trustee in the Atlantic Insurance Company and the South Brooklyn Savings Bank.

It was a good thing that neither of the founders were alive to see their business fail. Their new building cost more than they could really afford, and the company was deep in debt and running a deficit. In 1907, the president and vice-president resigned from the company. The store closed soon after. Today, the large Con Ed/CVS building stands in its place.

Although long gone, a part of Journeay & Burnham lives on at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, which has a Journeay & Burnham hat in their permanent costume collection. It is prized as a beautiful example of the late Victorian milliner’s art – well made in black velvet with rose and claret velvet roses, ribbons, beading, feathers, and trim. While it remains in their possession, Journeay & Burnham won’t be totally forgotten.

Related Stories

- Albert Korber and the Business of the Artful Home

- Music, Beer, and Cigars: A Concert Garden Comes to Brooklyn

- The Walled City: Brooklyn Heights’ East River Warehouses

Email tips@brownstoner.com with further comments, questions or tips. Follow Brownstoner on X and Instagram, and like us on Facebook.

I really love historical stories like this one. I even downloaded the PDF of the book you mentioned and have started to read it. Love Brooklyn history!