From Mansions to Housing for Navy Yard Workers: The Clinton Hill Co-ops Story

As World War II and construction of highways and public housing were changing Clinton Hill, service members and their families needed housing.

An entrance at the Clinton Hill Co-ops today. Photo by Susan De Vries

Thanks to Charles Pratt, the wealthiest man in Brooklyn, Clinton Avenue became a Gold Coast of mansions in the 19th century, but a housing shortage and changing tastes decades later saw many adapted for nonprofit use or razed for apartment buildings. One of the most notable complexes on the avenue today, the Clinton Hill Co-ops, was built during World War II as rentals for members of the armed forces or war-plant workers and their families.

A fashionable enclave

Back in 1874, Charles Pratt instantly became the richest man in the borough when he joined his very successful Brooklyn-based Astral Oil Company to John D. Rockefeller’s Standard Oil conglomerate. One of the first things he did was commission a large new family mansion near the corner of Clinton and Willoughby avenues. The Pratt family — Charles, his second wife, Mary, and seven of his eight young children — moved into their new home. One of Brooklyn’s early suburban havens, the avenue was lined with large wood-framed villas set back from the street and surrounded by spacious grounds.

When the sons married years later, Papa Pratt gifted them with their own impressive mansions, all just across the street or on the site of the old Pratt house. By this time, the old villas were passé, and wealthy entrepreneurs, financiers, and manufacturers were buying them to tear down and build even more lavish Gilded Age stone-clad mansions.

Charles and his sons encouraged their oil executive friends to move to the Hill, as it was now one of the most expensive and fashionable areas in Brooklyn. Several of them did and used their large fortunes to commission truly impressive homes. Of special note were the mansions of Standard Oil executive Edward T. Bedford and his son Alfred C. Bedford. They shared Clinton Avenue with industrialists like the coffee king John Arbuckle, baking soda millionaire Dr. C.N. Hoagland, elevator mogul Alonzo B. See, and many more.

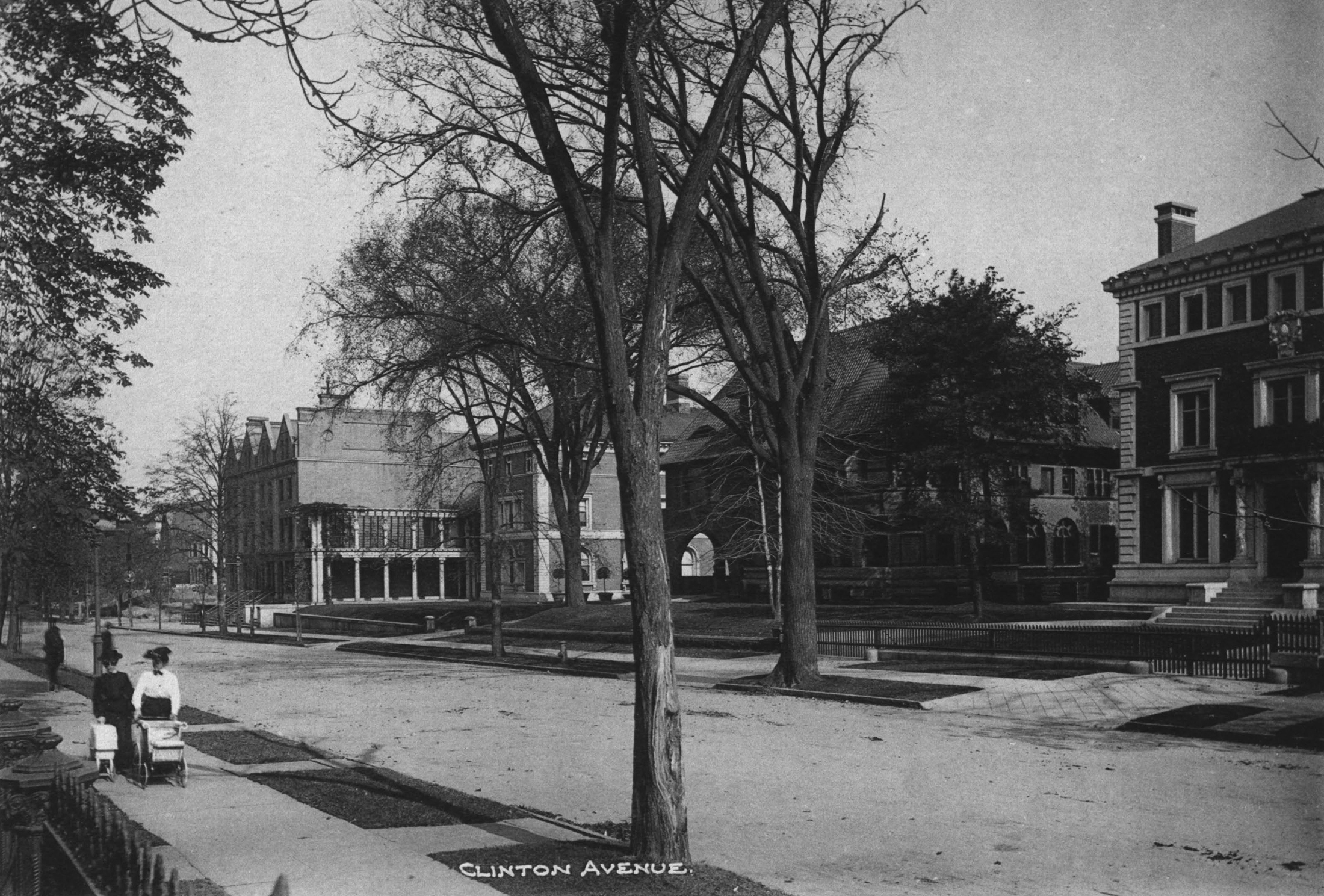

Period postcards and photographs of Clinton Avenue dated at the turn of the 20th century show a Gold Coast of mansions and fine townhomes on both sides of the street, especially between Willoughby and Lafayette.

Alas, even mansion blocks don’t last forever. By the end of the 1920s, many of the toffs of Clinton Avenue were decamping to the upscale suburbs of Westchester, the Gold Coast of Long Island, and to the elegant new apartment buildings in Manhattan.

Some of the large houses were torn down at that time and replaced by six-story elevator apartment buildings aimed at a new demographic. The sites where a family and their servants once lived alone now housed large buildings with hundreds of tenants. Clinton Avenue and surrounding blocks changed from an ultra-wealthy area to a more middle-class neighborhood, home to many first- and second-generation immigrant families.

All but one of the Pratt homes weathered the storms because of Pratt Institute and the Catholic Church. Frederick B. Pratt was Charles Pratt’s second son and served as the Institute’s president and trustee for 44 years. After his death, his wife donated the house at 229 Clinton to Pratt Institute, which renamed the house the Caroline Ladd Pratt house in her honor. The house served as a dorm for foreign students for many years. It is now home to the president of the college, with the parlor floor and grounds available for special events.

Even though the Pratt family were staunch Baptists, several of their properties were sold to the Catholic Church, which saved them from later destruction. Charles Pratt’s home and property, as well as George Dupont Pratt’s mansion at 245 Clinton Avenue became part of St. Joseph’s University. The magnificent home built for eldest son Charles Millard Pratt at 241 Clinton became home to the bishop of the Diocese of Brooklyn.

Other fine homes along the street were also incorporated into St. Joseph’s or became apartment buildings, private schools, club houses, and churches. Many of the row houses remained homes, some still single-family, while others were reconfigured as multiple-family dwellings or rooms with a kitchenette. Student and faculty apartments for Pratt Institute and St. Joseph’s helped keep the neighborhood occupied and busy well into the 20th century. However, the Great Depression, followed by World War II, changed everything.

Affordable housing and the World War II years

While Clinton, Washington and the surrounding blocks were thriving, the Wallabout neighborhood north of Myrtle Avenue and west to Flatbush Avenue was a different world. This was one of Brooklyn’s busiest industrial areas and one of the poorest in terms of income and housing. The city called it the Navy Yard District.

The residential areas in and around industry housed Navy Yard and factory workers and those who were at the bottom of the economic ladder. It was also home to a growing Black population who joined an already established Irish and other immigrant populations.

The elevated Myrtle Avenue line ran above blocks of deteriorating and abandoned wood-framed houses, row houses, and tenements. A study of the Navy Yard District conducted in 1939 by the city’s Real Property Inventory found on an average block 40 percent of the apartments had no private toilet and 100 percent were without central heat and hot water.

The Navy Yard, which employed over 7,000 men, wanted better housing in the neighborhood and pressed for new housing of at least 2,500 units for their employees alone. Housing advocates noted that it was more important to have housing for people than it was to build more highways for cars. An advocate for the African American population, which had doubled between 1910 and 1920, urged the city to build at least one low-cost project in the enclave, saying that the Navy Yard District would be “admirably suited for this purpose.”

This being New York City, studies of the area and the gathering of statistics went on for months. The 1939 World’s Fair opened in Queens that year and Robert Moses wanted to expand and improve his new Brooklyn-Queens Expressway so that drivers could get to Flushing Meadow more easily. Tillary, which had been a narrow street lined with tenement housing on both sides, was completely razed, refigured, and enlarged, with multiple lanes and ramps leading to the elevated highway.

That done, and widely praised, the city moved on to designate 40 acres of the Navy Yard District that would be demolished for new low-income housing. It took two years for the project to be designed, get through the city’s complicated bureaucracy, and for the existing buildings to be torn down. The project was collectively called the Fort Greene Houses and consisted of 35 buildings ranging from six to 15 stories tall. Construction began in 1941, and the first families moved in in 1942. The entire project was completed in 1944 and lauded by everyone, including Brooklyn’s retail businesses, which advertised special deals for new tenants.

But in the meantime, World War II had started. And it changed both the Fort Greene Houses and Clinton Avenue itself.

The United States officially entered World War II in 1941, after the December 7th attack on Pearl Harbor. But the country had been preparing for war much earlier. Although officially neutral, the U.S. had been supplying the Allied forces with arms and supplies since 1939. In Brooklyn, the Navy Yard was ramping up military operations and the Yard and surrounding factories were expanding their manufacturing capabilities. The Yard’s workforce and arriving military personnel and their families needed homes.

The Navy Yard also needed to expand, and once the U.S. was in the war, it also needed an upgrade in security. The Wallabout Market, Brooklyn’s wholesale produce, meat, and foods market was next door to the Yard. It was a large site, notable for its Dutch-inspired architecture, completed in 1896. It was a busy and profitable enterprise, and less than 50 years old, but military needs were more important. In 1941, the 54-acre market was slated for demolition. In its place would be two important dry docks for the construction of battleships and more factory buildings.

The fears of security breaches and sabotage were also uppermost in the Navy’s mind. The market was definitely not secure, so the fate of the Wallabout Market was finalized. The businesses were relocated to the new Brooklyn Terminal Market in Canarsie and the Atlantic Yards meat market, and the entire site was cleared that same year. Nothing was saved, and the Navy rapidly began its expansion.

The Fort Greene Houses were still under construction when it was decided that a large percentage of the housing would first go to Navy workers and their families. With the former residents of the area, the new people who were expected to move into the Houses, and the military personnel, it was soon apparent that more housing — specifically for the Navy officers, enlisted men, and their families — was desperately needed. But where to put it? New housing needed to be close to the Navy Yard itself.

Tearing down other industrial buildings was a no-go as they were all needed for wartime industries. Should blocks and blocks of Wallabout or Clinton Hill/Fort Greene row houses be torn down for new housing? That would involve a lot of eminent domain buyouts, even more displaced people, and no end of complications. Attention turned to Clinton Avenue, with its blocks of old mansions and once elegant row houses, many of which were underused and under populated. The former Gold Coast blocks between Myrtle and Greene were the best location for new wartime housing.

The Creation of the Clinton Hill Houses

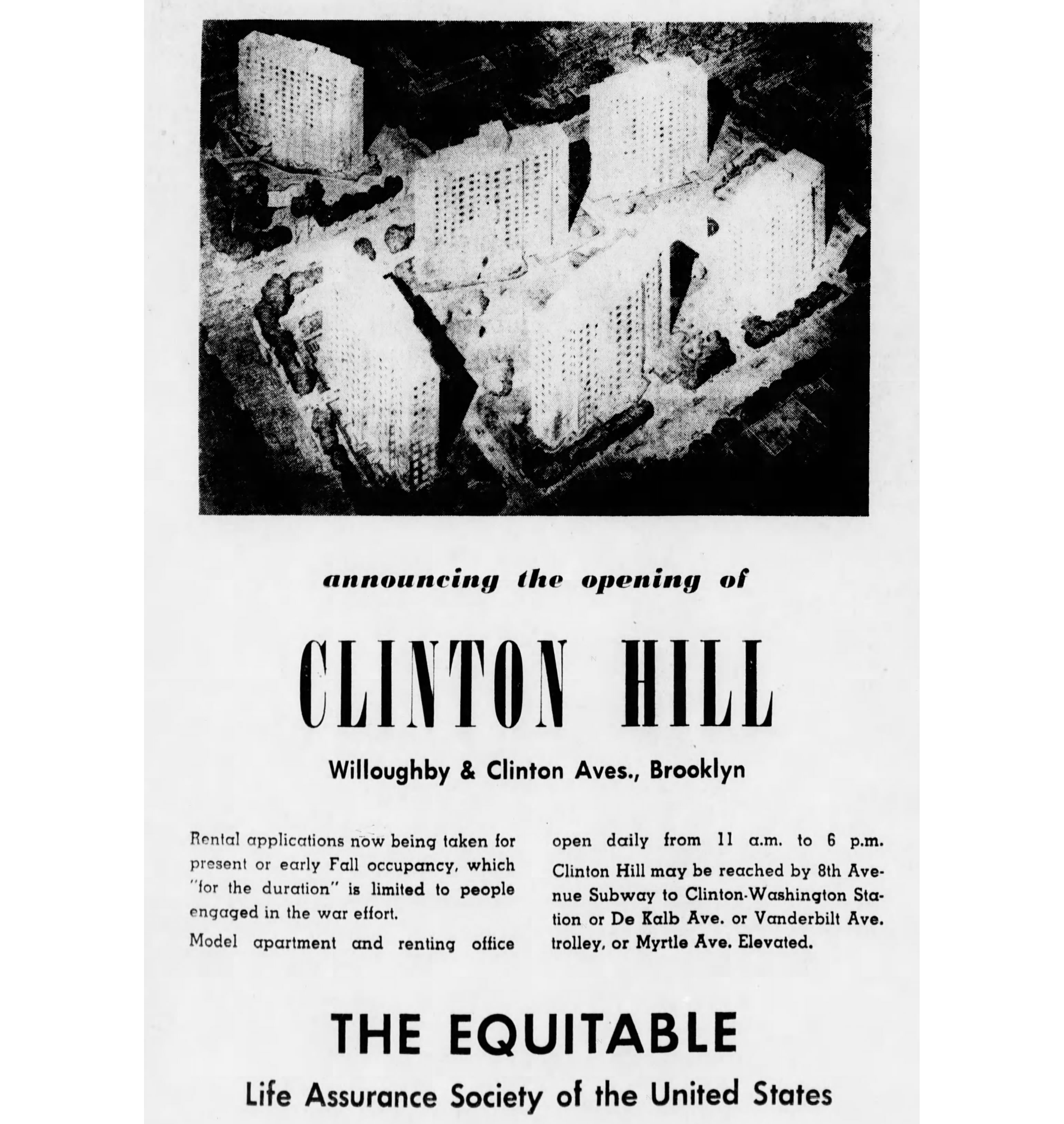

In January of 1942, the Equitable Life Assurance Company of America’s president announced that the firm would develop a new housing complex called Clinton Hill in the vicinity of Clinton and Lafayette avenues. The first buildings would house at least 1,200 defense families, including officers and servicemen. The official announcement was made by Thomas I. Parkinson, president of Equitable, at a luncheon at the Bossert Hotel.

An article in the Brooklyn Eagle went on to say that while the government was building low-income projects like the Fort Greene Houses, there were very few private projects for the middle class, such as Metropolitan Life’s Parkchester development in the Bronx. The Clinton Hill Houses would be similar to Parkchester and owned by the insurance company. It would consist of 10 to 15 apartment buildings of 12 to 14 stories. With the Luftwaffe’s London bombing raids in mind, the new housing would be built with new expanded fireproof techniques and sturdy materials.

The article also revealed that over eight months two real estate brokerage firms had secured the land needed for the project. The first phase would be apartment buildings on Clinton Avenue between Myrtle and Willoughby avenues. Another article announced the destruction of Herbert L. Pratt’s mansion, on the west side of Clinton Ave at Willoughby. Also going under the bulldozers were the “old-time dwellings” across the street.

This included the former homes of E.T. Bedford and his son Alfred. They had decamped to Manhattan and Connecticut years before. Their homes were touted in the society pages only a few decades prior as being among the most lavish on the Hill, designed by one of Brooklyn society’s favorite architects, Montrose W. Morris. Not only was E.T. Bedford’s home impressive, so were the luxurious stables for his prize horses, meriting a full-page article in 1900 describing them. The large stable was located behind his house on Waverly Avenue, and it too, as well as everything else on that side of the block, fell under the wrecking ball.

The nearby Fort Greene Houses were a government project, and subject to all the delays and red tape that always accompany such things. The Clinton Hill Houses were a private development, so it was able to move much faster. Equitable Insurance hired the architectural firm of Harrison, Fouilhoux and Abramovitz to design the complex. They were proficient in designing campuses with tall buildings such as this.

Harrison and Fouilhoux were among the architects of buildings in Rockefeller Center, built only 10 years earlier. Wallace K. Harrison was the project’s primary architect. He later designed the Met Opera in Lincoln Center, the United Nations buildings, and the Empire State Plaza in Albany. The construction was undertaken by Starrett Brothers & Eken Inc., also experienced in this type of building.

By March of 1943, the first three buildings in what was being called the “defense housing community” were ready to rent. Three hundred families would be able to move in that June. A rental office was set up and a model apartment was available to tour. It was completely furnished by the donations of Abraham & Straus, using their modern line of apartment furniture. (A&S chairman Edward C. Blum was on Equitable’s board of directors.)

The apartments were simple and modern, with an L-shaped living room and dining nook separated from an L-shaped kitchen by a pantry. (A March 1942 Pencil Points article on the complex shows a floor plan and cutaway view.) A sale listing from a few years ago for a one-bedroom in the complex reveals a number of apparently original finishes, including wood kitchen cabinetry and a mostly intact bathroom with faceted pedestal sink, gray square wall tile, and gray and white basketweave floor tile.

The new buildings were in line with the 20th century architect Le Corbusier’s visions of tall apartment buildings set within a park. This was the model for most of NYC’s housing complexes. The upper floors of the new buildings afforded their inhabitants views of the Manhattan skyline, the East River, or the hills of Long Island. The Navy Yard, Fort Greene Park, Pratt Institute, and other schools were all within easy walking distance. The Myrtle Avenue elevated train line probably ruined some of the northern views and peace and quiet, but it and several bus lines were readily accessible.

For several months afterward, the Brooklyn papers featured articles and full-page ads aimed at the new tenants. Abraham & Straus led the way with the advertisements. Gone was the kind of heavy furniture that would have graced the demolished mansions. The store advertised light and multi-purposed furnishings that could be folded up and easily moved around. The furniture was made of veneered plywood, and various elements could be stacked and fit inside other pieces.

The ad stated that the apartments were planned for people who lived on rationed time. An advertisement for a line of goods from Pakto Furniture stated that, if necessary, two rooms of their furniture could be folded up and packed in a 6-foot crate. One never knew when the call would come to be stationed somewhere else.

So, what kind of people lived in the new housing? Equitable president Parkinson told the papers that everyone from a “psychologist to lathe operator” lived there. The initial applications were restricted to defense workers and service people. Engineers seemed to be most prevalent. They worked for the Navy, but also for Brooklyn’s Sperry Gyroscope and Mergenthaler Linotype, both now defense contractors. The first applicant to sign a lease was Lieutenant Commander Nathaniel D. Hubbell, who moved there from Clark Street in Brooklyn Heights. Another early tenant was a doctor who moved to the Houses from Long Island.

The next phase of the project, which included the remaining three buildings of the first group, proceeded. The second group, two blocks away, consisted of a building on the north side of Lafayette Avenue and six more across the street stretching from Clinton to Greene Avenue. Ground had already been broken and the foundations laid as the first tenants were moving into the first group that June of ‘43.

More mansions, townhouses, and carriage houses fell to accommodate the new construction. Clinton between Lafayette and Greene was home to Alonzo See, president of A.B. See Elevator Company, an early rival of Otis Elevator. He was a rich eccentric who became famous for his rants about women’s intelligence and education. Next door to him was a huge mansion that had been built in 1887 for millionaire wallpaper manufacturer Robert Graves, and was called “Graves’ Folly” for its size and expense. Both Graves and his wife died before moving in, and the property was bought by another Standard Oil man, Alfred J. Pouch.

Pouch was a passionate art collector and built an additional annex to house his collection. The mansion itself was filled with the finest furnishings and decor. Being a very social man, he began hosting charity and special events in his home, giving Brooklyn society an upscale place to gather and socialize.

Pouch began hosting so many events and renting smaller rooms upstairs for meetings that the family eventually moved to a house around the corner. Pouch died in 1899, his wife in 1905, and the house became a full-time event space. “The Pouch” as it was now called, hosted weddings, dances, concerts, charity events, meetings, and more. The rooms on the upper floors were rented to artists and musicians as well as smaller organizations. Composer Aaron Copland had his first piano lessons here.

By the late 1930s, the property belonged to a club. In 1942 they sold the Pouch to the Equitable Insurance Company for an undisclosed price. It was well known that the house, along with the entire block, was going to be razed for the Clinton Hill Houses. While the building was being demolished, it caught fire, destroying anything that might have been left of it.

The second phase of the Clinton Hill houses was finished a year later, with Navy officers and their families preferring this section of the complex. Any units not claimed by military families or war-related workers were offered to the general public, and the entire complex was soon completely occupied.

After the war, the Clinton Hill Houses became the owner-occupied Clinton Hill Co-ops. Because the buildings were better constructed than many other examples of wartime housing, they remained in excellent shape and are still well maintained today. The Co-ops contributed to the stability and economic growth of the neighborhood, providing housing for a large number of invested middle class residents who grounded Clinton Hill during the city’s turbulent times. One could well argue that had it not been for this well thought out and well designed complex, more of Clinton Hill’s treasures would not have been here to be saved.

Related Stories

- The Walled City: Brooklyn Heights’ East River Warehouses

- The Lost Crown Heights Mansion of a Typewriter Tycoon

- How the Railroad Brought Meatpacking to Fort Greene

Email tips@brownstoner.com with further comments, questions or tips. Follow Brownstoner on X and Instagram, and like us on Facebook.

Very interesting, in-depth article. I lived in Clinton Hill Apartments from 1962 til 1987 and knew some of the history – but not as much as was contained in this article. Thanks so much!