Locals Push Back on 27-Story Tower Planned for Historic Fort Greene Church

CB2’s Land Use Committee voted against the proposal for the 27-story development, which would rise from a landmarked Fort Greene church.

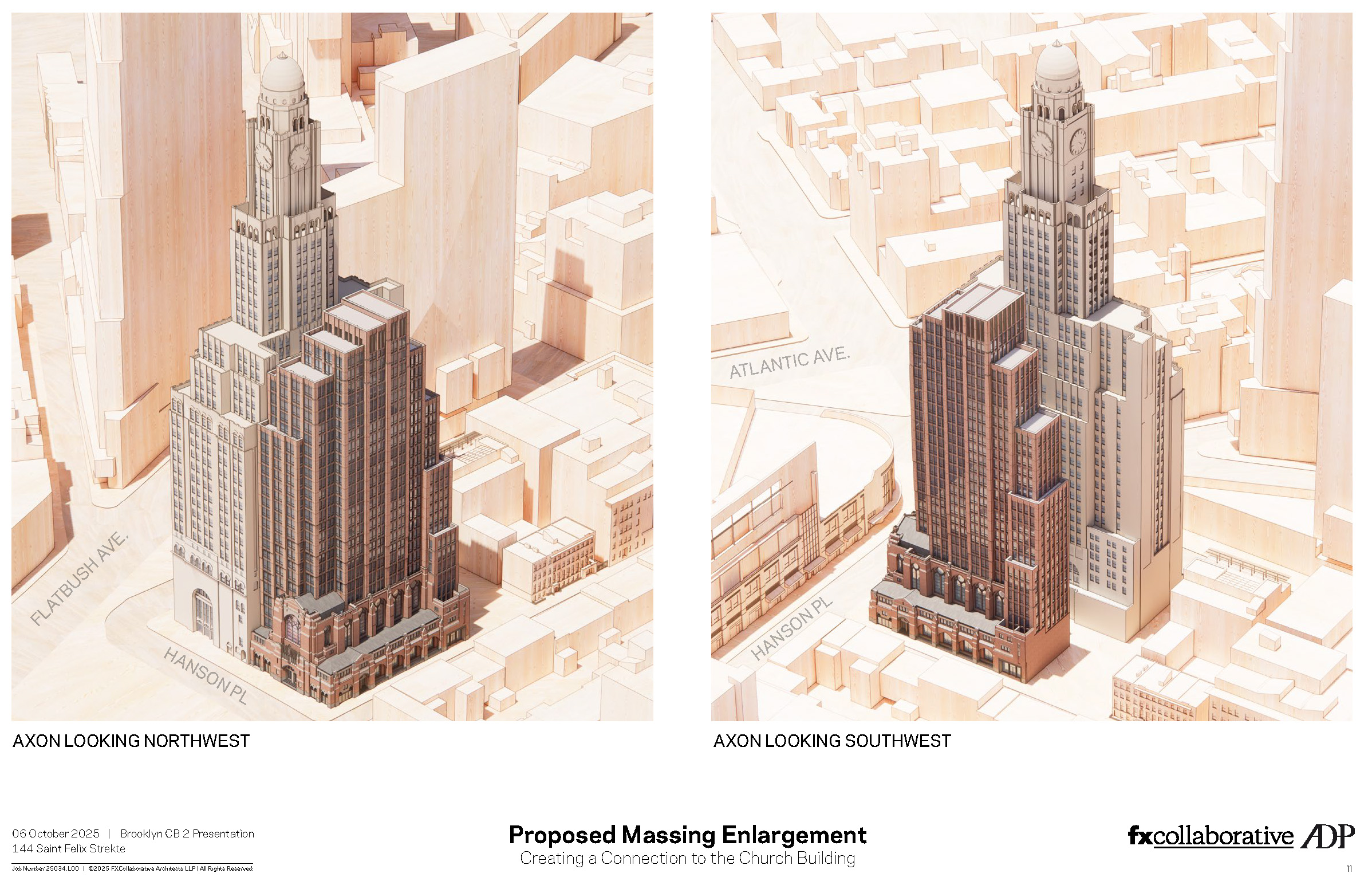

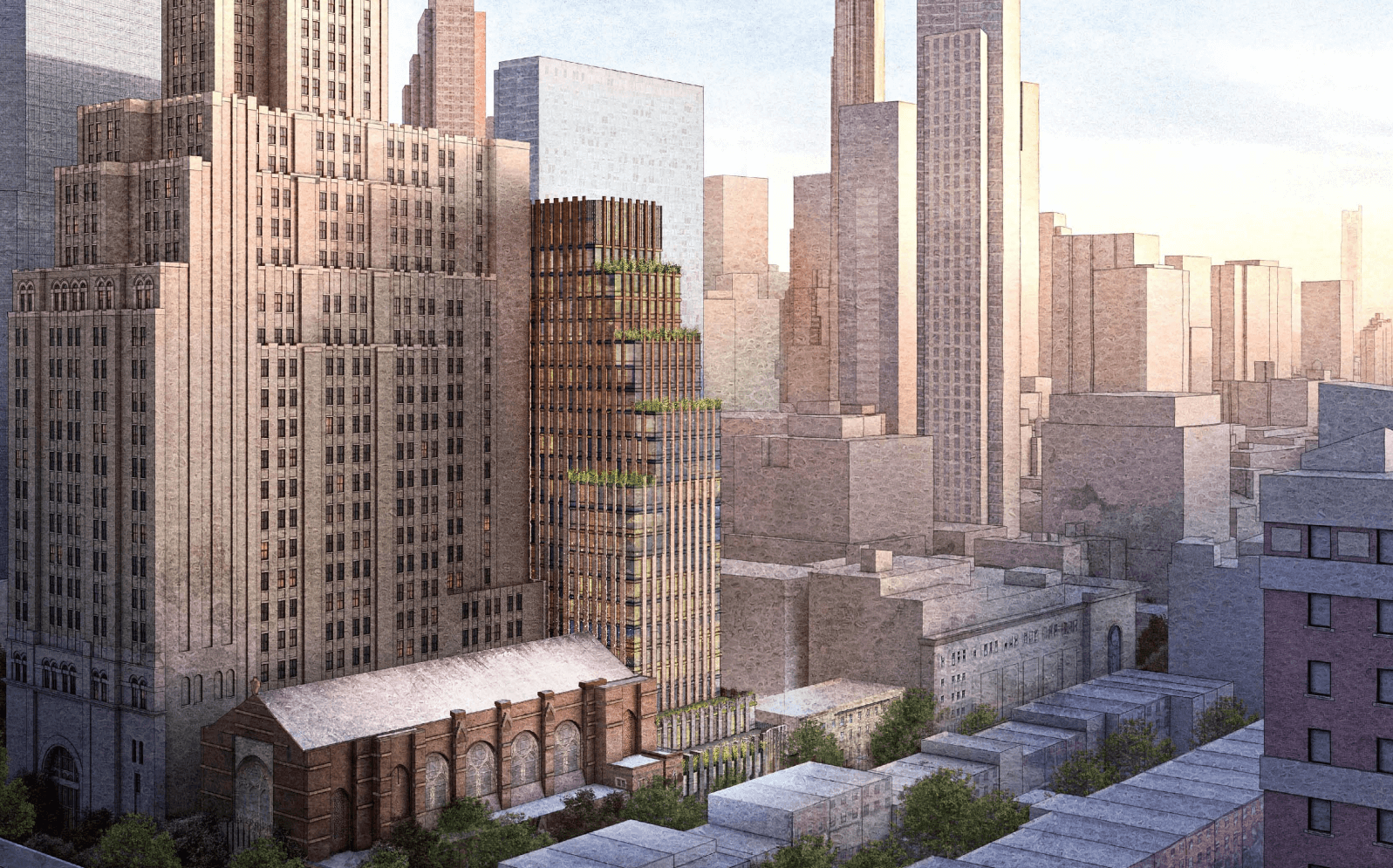

Rendering by FXCollaborative and ADP Architects via CB2

After more than a year of speculation about the future of the landmarked Hanson Place Central United Methodist Church in Fort Greene, plans are now clear: The owners want to use the church’s shell as the base of a 27-story, 240-unit apartment tower that would rise beside the iconic Williamsburgh Savings Bank Tower.

On Wednesday, the development team presented the proposal to Community Board 2’s Land Use Committee, outlining plans to convert the early 1930s neo-Gothic church at 144 St. Felix Street into a high-rise residential building. While some support was signaled for the project, it was largely met with criticism from locals and board members, an attendee told Brownstoner.

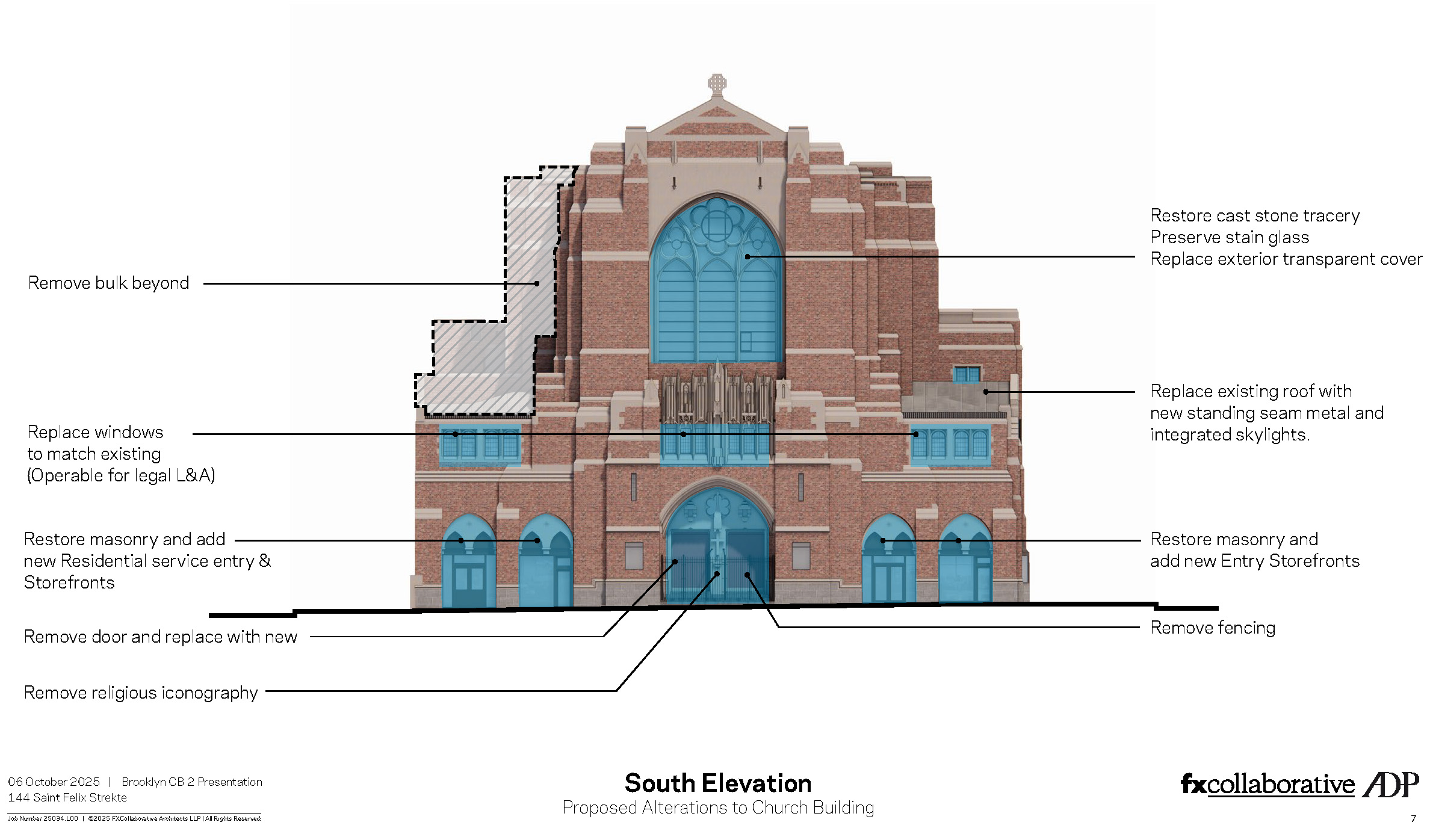

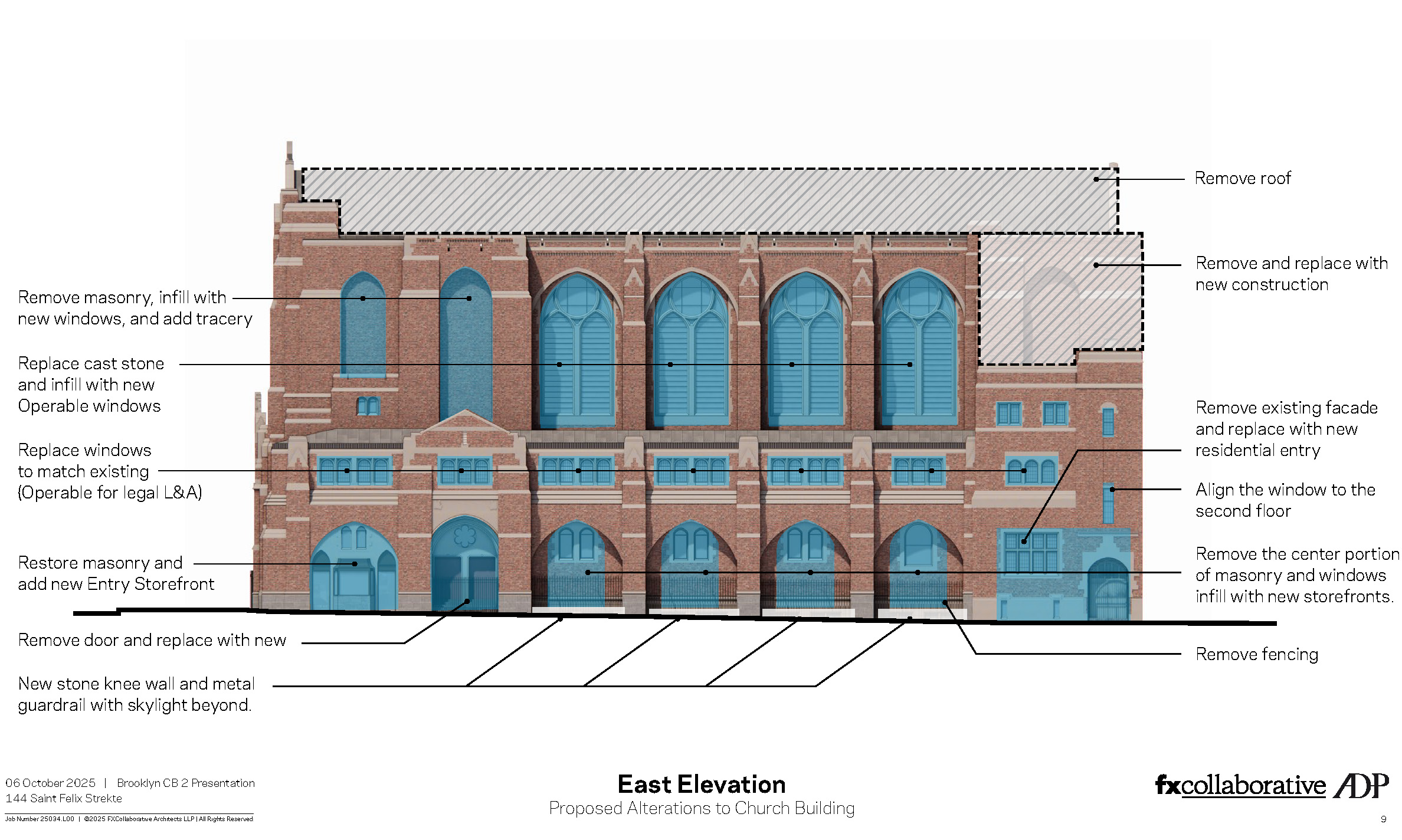

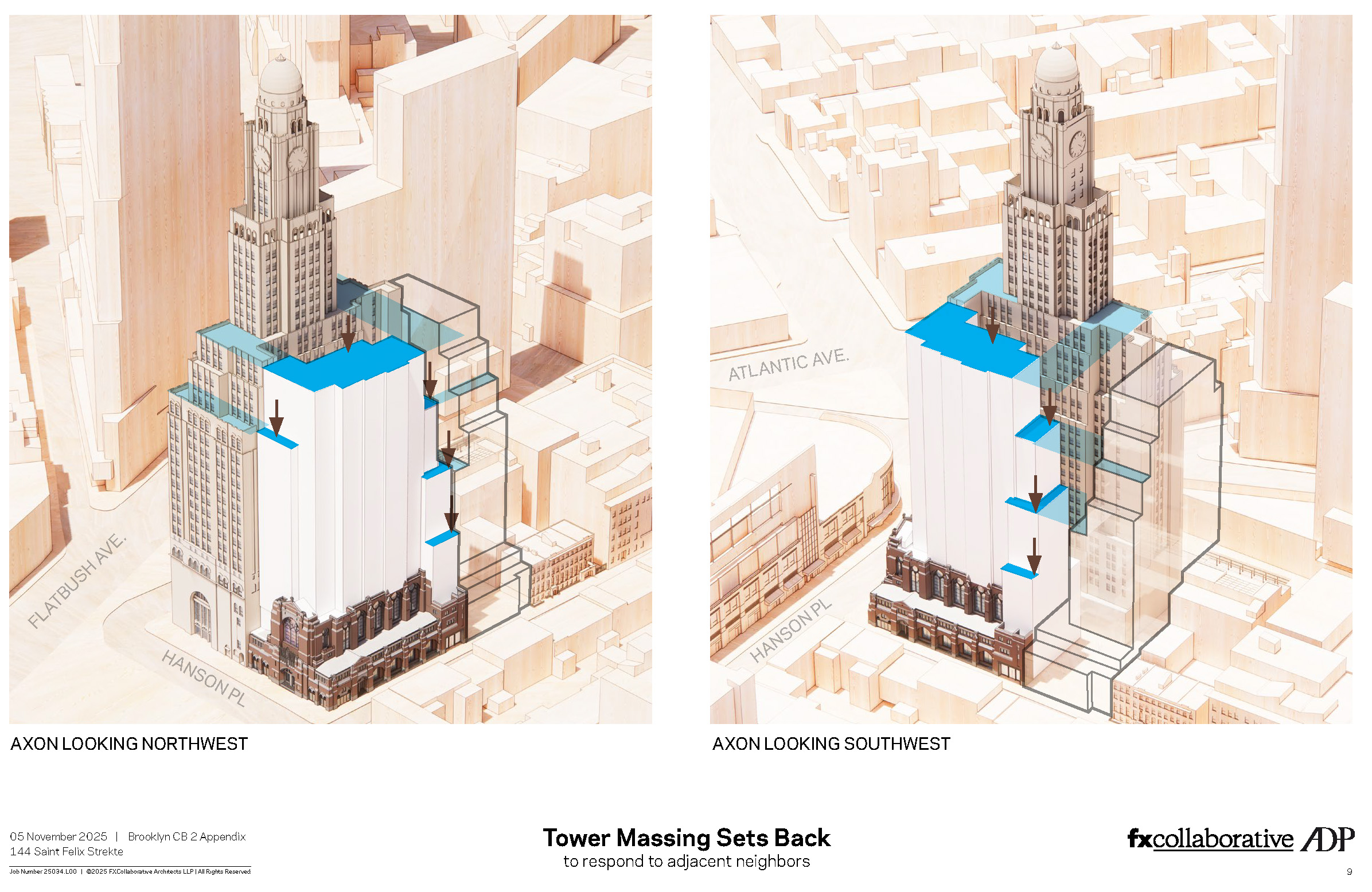

The project includes restoration of the church’s facades on St. Felix Street and Hanson Place; repairing masonry and cast-stone ornamentation, restoring stained glass, removing and preserving religious iconography, replacing windows to meet light and air requirements, and adding new doors, skylights, a roof, and retail and community spaces. The attached 27-story brick-clad tower, which would step down along both Hanson Place and St. Felix Street, would contain 240 apartments, 60 of them permanently affordable, the presentation says.

According to the presentation, Strekte is the developer behind the project and FXCollaborative and ADP Architects (ADP is also behind the controversial proposed tower at the Duffield Street Houses) are working on the designs. The team describe the project in the presentation as “a thoughtful approach to historic preservation that saves a deteriorating landmarked building.”

However, board members and residents pushed back on that, and the committee ultimately voted to disapprove the plan (four members were opposed, two in favor, and there was one abstention).

According to a local resident, around 25 community members spoke at the meeting and the majority were against the proposal. The condo board at One Hanson Place told Brownstoner in a statement following the meeting, “we are not opposed to the reasonable development of 144 St. Felix Street. However, we believe the proposed residential tower is out of character for our historic neighborhood and inappropriate for the site.”

Before the meeting, the community board received 73 written comments in opposition to the project and 32 in support. Opponents cited blocked views of the Williamsburgh Savings Bank Tower, harm to the historic district, and concerns about traffic and infrastructure. Supporters said the plan would restore a long-vacant property, add housing, and boost property values.

“There may be no private right to a view, but this plan damages shared public views and the historic character that defines our neighborhood,” one One Hanson Place resident wrote. Another said the proposal “destroys” the church’s architecture and disconnects it from the community.

“The BAM Historic District is not just old buildings, it is the everyday backdrop for art and community. The tall building proposed for 144 St. Felix feels out of touch with that spirit. It would dominate the block and break the careful beautiful scale that lets the current church, the streets, and the skyline speak to each other,” a local resident wrote. One commenter said protecting public views of the clock tower at One Hanson Place was essential to preserving the district’s character.

While another wrote: “While I understand the difficult circumstances of the church, the proposed plan is a disservice to architecture of the Hanson Place Central United Methodist Church, and the immediate neighborhood. The high-rise atop the church looks disfigured and overwhelming.”

Supporters of the plan countered that the project would stabilize a long-vacant site and provide affordable housing. “The only way to preserve any identity of the structure is for an intervention and restoration,” one wrote, adding “New York City is also facing a record housing shortage which this would help to alleviate for Downtown Brooklyn and the surrounding neighborhoods while supplying much needed affordable housing.”

Another commenter said the project would “bring long term stability to a site that has been left unused and in despair for many years.”

“A vacant building in poor condition attracts problems, and drags down nearby blocks. Putting it back into use with more affordable housing is best case scenario,” they wrote.

The full board will vote on November 19 before the proposal heads to the Landmarks Preservation Commission. Although not individually landmarked, the church sits within the Brooklyn Academy of Music Historic District, meaning any changes require LPC approval.

Designed by Halsey, McCormack and Helmer — the same architects who designed the iconic Williamsburgh Savings Bank Tower next door at 1 Hanson Place — the neo-Gothic church was constructed as the Central Methodist Episcopal Church. The building at 144 St. Felix Street includes extensive use of terra-cotta ornament and tile work on the interior and exterior from the Atlantic Terra Cotta Company. Its cornerstone was put in place in December 1929.

In early 2024, the congregation sold the property to an LLC backed by Wolfe Landau of Watermark Capital Group for $15 million, citing dwindling membership and rising maintenance costs. The congregation had already relocated services to Grace United Methodist Church in Park Slope.

According to Crain’s, to close the sale Landau secured funding from two entities, Bambh and Strekte, which it said were connected. As part of the deal, Landau reportedly agreed to split ownership with Bambh’s members, identified in court documents as Harry Einhorn, Paul Jensen, and Mark Rigerman. In January, Bambh sued Landau, alleging he failed to honor their agreement. Landau later countersued, accusing the group of attempting to dilute his ownership stake.

At the recent community board meeting, representatives for Strekte said the firm had since acquired all rights to the property from Watermark, a local resident told Brownstoner. City records still list the LLC backed by Watermark Capital as the owner.

Behind the church, the lot at 130 St. Felix Street remains undeveloped and in question. In 2021, City Council and LPC approved plans for a controversial 23-story condo tower on the site, which would include affordable condos and space for the Brooklyn Music School, but the development has stalled. FXCollaborative was also working on those plans.

City records show no new building permits have been filed for the project, though in October 2024 a permit application was submitted for foundation work related to a previous plan for a parking lot with 39 lifts for 58 cars. The site has long been used as a parking lot. Brownstoner reached out to owner Gotham Organization for comment, but did not hear back by publication.

[Photos by Susan De Vries unless noted otherwise]

Related Stories

- Fort Greene Church Inks Deal for $15 Million Sale Next to Stalled Controversial Condo Tower Site

- Building of the Day: 1 Hanson Place

- Brooklyn Music School, Local Stakeholders Support Fort Greene Tower Expansion

Email tips@brownstoner.com with further comments, questions or tips. Follow Brownstoner on Twitter and Instagram, and like us on Facebook.

The Hypocrisy of One Hanson Place Reaches New Heights

For nearly a century, the owners of One Hanson Place (the old Williamsburg Savings Bank Tower) have wrapped themselves in the flag of “historic preservation” while blocking desperately needed housing next door.

Let’s remember what they’re actually “preserving”:

In 1928 the bank couldn’t get a branch license here until they promised to lend into the surrounding Black and immigrant neighborhoods. Over the next 50 years they extracted $932 million from Brooklyn while lending only $32 million back to the community that money came from, diverting 97% ($900 million) to their wealthy white clients elsewhere. Classic redlining, plain and simple.

When they tried designate the building this a landmark in the 1970s, Congressman Fred Richmond publicly protested the proposed Landmark designation NOT to make this tower “a monument to bad history.” The bank cut a deal: they’d create a $10 million community lending fund (less than 1% of what they choked and stole generational wealth from) and in exchange got the landmark designation they now weaponize.

It gets worse.

Having learned that rules are for little people, the bank’s successors illegally replaced 906 historic windows, radically altering the building’s appearance without Landmarks approval. They were caught, violated, and fined, then turned around and vacuumed up over $60 million in taxpayer-funded preservation grants meant for actual stewards of history.

Now the same crowd is back in front of the Landmarks Commission, clutching their pearls and crying “context!” to stop a beautiful, perfectly massed residential building on the shell of church next door, the bank walls facing this church were deliberately left blank and windowless BECAUSE THE ARCHITECT ALWAYS EXPECTED A BUILDING TO RISE THERE.

This isn’t preservation. This is generational thieves who redlined Brooklyn and Fort Greene, gamed the landmark system, broke the rules they now hide behind, gorged on public money, and are still trying to control what the rest of Brooklyn can build, because God forbid anyone else gets housing.

The proposed building is elegant, contextual, and exactly what that site has waited 95 years for.

One Hanson Place had its chance to be a good neighbor. They chose exploitation then and they’re choosing it now.

Build the damn building.

I love this idea! More developers should work on preserving the original integrity of classic sites while building up the neighborhood!

I like it. Preserving a landmark only matters if future generations feel connected to it. The building in its current form speaks mainly to people who remember the past, but the neighborhood around it is evolving. By restoring the original structure and adding a thoughtful, contemporary element, the project doesn’t erase history. It strengthens it. It gives the next generation a reason to care about the landmark instead of walking past it.

I agree the clock tower should be a consideration as part of the design of the building next door. The building should compliment that element better. The elevation should be changed to mimic that building elevation. The building behind at 130 should also compliment the new building and why not mimic the churches design for the Brooklyn Music School for “acoustical” purposes?Fantastic!

All Kinds of NO!