'Slumlord Millionaire' Documentary Film Spotlights Fight for Affordable Housing

The documentary film investigates the real estate industry, its ties to politics, and issues of housing justice through four interwoven stories.

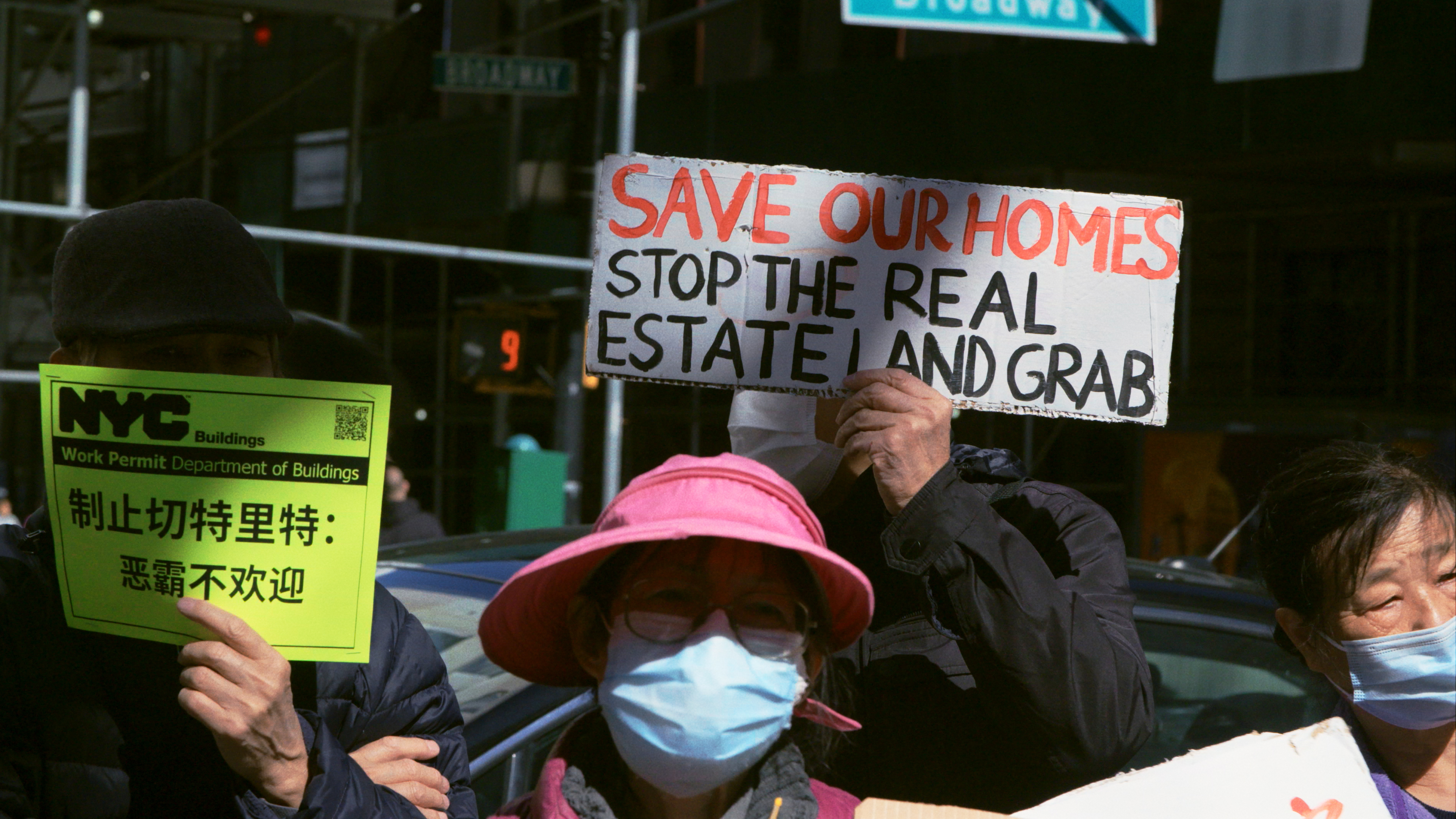

Samantha Bravo-Huertero and CAAAV: Organizing Asian Communities at a Rent Guidelines Board rally. Photo by Steph Ching

A documentary that first screened at the DOC NYC film festival in 2024 and earlier this year explores the city’s affordable housing crisis through poignant stories of New Yorkers fighting tenant harassment, deed theft, and the power of the real estate industry.

The action-packed Slumlord Millionaire shows how various aspects of the affordability crisis in the city are interconnected through its articulate and charismatic subjects. Sometimes they win but the losses, at least so far, outweigh the victories and the film leaves viewers feeling sad, outraged, and motivated. The film will have its broadcast premiere on the PBS show VOCES on July 28, can be viewed at screenings in Brooklyn and Manhattan starting July 26, and is available for private screenings.

Winner of the Audience Award at the 2024 DOC NYC Film Festival, Slumlord Millionaire was directed by Steph Ching and Ellen Martinez, who met at New York University’s film school and previously made the documentary After Spring on the Syrian refugee crisis. The latest project, largely funded by PBS, was filmed mostly in 2022 and took five years to make.

Slumlord Millionaire follows the Bravo family’s experiences with their landlord in Sunset Park, Janina Davis’ struggle to reclaim her Bed Stuy house after losing it to deed fraud, a group of Chinatown activists trying to stop luxury development due to fears of displacement, and Moumita Ahmed’s 2021 run for City Council in Jamaica, Queens. The documentary paints a picture of real estate developers seeking to kick New York’s low income and middle class renters out of their homes and replace them with luxury towers filled with high earners.

Speaking to Brownstoner, Ching, a lifelong New York resident, and Martinez, originally from Texas, said they created Slumlord Millionaire to explore the battles ordinary New Yorkers are facing against a powerful real estate industry to secure safe and affordable housing.

Why did you decide to make this film?

Ching: We’ve lived here for a very long time, and I’ve seen our neighborhoods transform. Actually one of our really good friends, she’s the housing consultant on the film, Morenike Fajana, she used to work as a housing attorney at Legal Aid Society many years ago and she would tell us these stories of her workday, you know, going to housing court and doing eviction defense for tenants, and particularly rent stabilized tenants who are being pushed out of their homes from landlord harassment, so we would hear these stories and thought, you know, why haven’t people been covering this as much? We saw a little bit about it in the news, but we hadn’t found a documentary that really focused on that. So that was initially our entry point into the film was the landlord harassment and tenant organizing part of it. And then as we dug deeper into the story, we started to find how interconnected all of these other issues were. So that’s how we focused on Chinatown with the developers and their huge presence on the waterfront, and then also finding how politics is vastly influenced by the real estate industry. I mean, we saw that a lot with this most recent primary election. But we found Moumita’s story actually online, on social media, and that was the first time we had seen that level of money being pumped into these relatively small local elections. I think people are used to seeing money being a big part of politics, but not understanding that it trickles down into every corner of local politics as well. So we really wanted to focus on her story, and the fact that these billionaire developers pumped a million dollars into a super PAC against this one race really kind of put things into perspective for us. And then the last story about deed theft, that was something that was really kind of new to us. We hadn’t really heard about it and hadn’t seen it covered that much. And we actually found Janina, the person in our film who is going through that, at another tenant rally. We had shown up at this rally, we were following this other tenant union and they were covering this other story of a family that was dealing with this, and she spoke at the rally saying that this had happened to her many years ago, so this is an epidemic that’s been going on for many years. So that was something that we wanted to fold into the story as well, showing that it’s not just landlords versus tenants, but also, but it’s more kind of these giant wealth holders, you know, billionaire developers, predatory landlords, all of that, versus kind of your average resident who’s just trying to live and work in New York City.

Is there any particular neighborhood that you feel a connection to that was featured?

Ching: Part of it is Chinatown. So my family’s from Hong Kong, and while they didn’t live in Manhattan, that was where my family first found community. They spoke the language, they could find food that, you know, they were used to, and the ingredients, and all of that. So my family has been here for several decades now and my grandma went to Chinatown basically either every day or every other day until she passed. So Manhattan Chinatown has especially been really special to us, and that’s part of the reason why we wanted to feature that.

Could you expand a bit on how and why you found the different cases that you focus on in the film?

Martinez: I mean, each of these different stories could have their own feature film. They’re just amazing people, incredible stories in their own right. And like Steph mentioned, we did want to include them all in the same documentary because then it shows the interconnectedness of the issue. It’s not just one thing. But we did start with the landlord repair issues. So we first met the Bravo family way back in 2019 we connected with them and I mean immediately we knew that if they were interested in being in the project we wanted to include them, just because they had such a long fight with the landlord. And the landlord was very extreme, as the attorneys say in the film. I mean, they actually took her to the Human Rights Commission and they passed a law because she was not taking care of mold and issues in the apartment affecting the children’s health and that that was a big deal, and they were really, really powerful in this fight, so we knew we wanted to include them. And then after that, as Steph said, the politics, we saw Moumita’s campaign on Twitter as she was being attacked. We reached out to her and were fortunate enough to get some footage throughout her campaign. She actually had other documentarians following her during the campaign, so we were able to tell that story also over time. And Janina, we met her at a rally, and then Chinatown, you know, Steph and her family had that connection. We already knew about CAAAV [nonprofit organization CAAAV: Organizing Asian Communities]. So, yeah, I’m really happy that we found all these four stories and they agreed to be a part of the film.

Did anything surprise you in the course of making the film and what are some of your biggest learnings from it?

Martinez: I think, first of all, deed fraud. I mean, we had never heard about deed fraud before and just the level of the tactics and level of the predatory scam that they are able to do and really there are very few laws, or barely any laws at all, that are actually preventing people from doing this. So deed fraud definitely was most surprising.

The subjects of the film win some of their fights, but they don’t necessarily win all of them. I’m sure you did get very involved with all of the different cases that you were focusing on. What are your thoughts on how things turned out?

Ching: I feel like a lot of this, again, goes back to the understanding about how interconnected these systems are. While there were some individual wins that were really great to celebrate, you know, for instance, the Bravo family getting the Asthma Free Act passed here in New York. And also them being able to take their landlord to the Human Rights Commission and actually get some settlement through that, that was a really positive success, but I think the biggest learning, and, you know, talking to all the organizations and activists involved is just how ongoing this fight is and how it is a bigger systemic issue, and how really the way forward is organizing with your neighbors and with your community and being able to kind of tackle each of these problems as part of this larger system. So, you know, it’s been really great since the film ended seeing the work that everyone’s been doing since then. For instance, the Bravo family, they actually have a new landlord now, which is a really exciting update. I think part of it was just the market, but part of it also really had to do with the pressure that was being put on the landlord by the tenants organizing and not putting up with the harassment. So, you know, landlords don’t like dealing with that. It costs them money, too. So she sold the building, so now they have a different landlord that is not doing all those things to them, actually listens to their repair concerns and all of that. So that’s been really exciting. And also seeing the family becoming even greater leaders within their community has been really exciting to see. Samantha, she’s in college now, and she’s really come into her own as this tenant activist and Fabian, the father, he works with Neighbors Helping Neighbors right now, on staff, and we’re seeing similar things happening with these other organizations too, like, for instance, CAAAV, all those members, they created CAAAV Voice, which is their partisan arm. So they were really, really vocal in this most recent primary election race. And yeah, it really goes back to organizing, even Janina with deed theft through this process, she’s found a lot of other families who have either also gone through this, or are currently going through this, and they’ve formed this coalition together where they’re tackling this more head on, with support from each other, you know, sharing resources in terms of lawyers and new legislation that’s being suggested. So again, I guess community organizing is kind of the big takeaway for us and something that does feel hopeful moving forward.

Martinez: Quickly to add to that too, it’s a really exciting time for [the film] to come out with this recent primary. I mean, the mood, like Steph said, could even be seen as hopeful now. A big campaign thing people are running on is freezing the rent, affordability in the city. And I think our film really shows how the cost of living here is affecting people, and each of the different groups were involved in this recent campaign.

My takeaway was politics and real estate seem to be in bed with each other in trying to push out people who are in more affordable housing, housing that they see as something that could be more commodified into something luxury, towers. Was that something you intended to communicate, and if so how did you come to those conclusions?

Ching: I think one of the big things is living here as these things are happening has shown us what’s at risk of being lost in the city. What makes New York so incredible is that you have all of these people from all these different backgrounds who are able to live together, share our cultures, share our food, share everything, and we’re living on top of each other. And you have to learn how to get along. So I think seeing these towers go up and these historic communities, and particularly communities of color, being pushed out of their neighborhoods is really impactful to us. And I think it’s very stark, you know, the neighborhoods where this is happening, and we really don’t want to see the character of New York be lost — again, that’s what makes it so special.

There is the argument for rent stabilized buildings, landlords say, well, we need to raise rents because we can’t afford to maintain these buildings that are aging. Or if we build more towers, it’ll actually lower the cost of rent for everybody. What would you say to people who push back on the message of the film and say that maybe building more is the way forward?

Martinez: Yeah, definitely. I mean, it’s of course a very complicated issue. And which you know, you report on it. So, you know, the film is called Slumlord Millionaire. So we did clearly focus on the bad landlords and the clear bad actors here. And we would argue that the smaller landlords like Janina are also caught up in this crisis. There is something that needs to be done to help preserve these buildings and also make sure that people are able to afford to live here. The difference between the billionaire developers and the mom and pop landlords is pretty extreme, so they all kind of are caught up with the tenants in the crisis.”

You mentioned the current environment gives you hope. I will say I felt very sad leaving the theater. I felt hopeful and inspired, but also sad. So for someone who feels inspired but also a little bit hopeless after watching the film, what would you recommend they could do to help improve housing in the city?

Martinez: I mean, I think the biggest thing is finding your community organizations and mutual aid groups. There’s tons of tenants unions around. We also have an impact campaign that we’re working on with our film, bringing the film to different neighborhoods and having these community conversations. And our website does have resources that direct people to different organizations that are in this fight. But I think that the biggest thing is get involved in whatever way you can. And it doesn’t even have to be being involved with a formal organization, it could just be actually talking to your neighbors and knowing who lives across the street from you. We saw this a lot with this most recent primary, you know, grassroots organizing can make change, and I do think that’s the only way we are able to tackle this problem. I mean, regular people are never going to be able to raise the capital to compete with $30 million for a super PAC. It’s just not going to happen. But what we do have is power in numbers and power in actually caring about each other. So I think there’s a lot to be said about just talking to each other and knowing that you’re not alone in your struggle. I think that was something that was really big for all of the participants in the film, was them learning that it’s not just me against my landlord, it’s me and all my neighbors in my building, and all my neighbors on my block being able to join together and fight back. So we hope that’s something people take away.

Editor’s note: Answers have been edited and condensed for clarity.

Related Stories

- How New York City Can Create Genuinely Affordable Housing

- What Is Affordable Housing?

- NYC Has More Housing Than Ever Before Yet It’s Still Not Affordable

Email tips@brownstoner.com with further comments, questions or tips. Follow Brownstoner on Twitter and Instagram, and like us on Facebook.

What's Your Take? Leave a Comment