Designed for City Living: The Row House Plans of Robert G. Hatfield

Floor plans from an architect who moved to Brooklyn around 1873 reveal how row house living changed over the course of the 19th century.

Elevations and floorplans by Robert G. Hatfield. Images via editions of The American House-Carpenter

Poring over floor plans can easily become an old house lover’s obsession. Where was the kitchen when the house was built? Was there originally a fireplace in the front parlor?

If row houses are your particular obsession, some original plans can be turned up with some hunting through archives or in publications like Bricks and Brownstone: The New York Row House, but another potential source of information are the builders guides and pattern books of the 19th century. Many are now more readily available for perusing online.

Books for Builders.

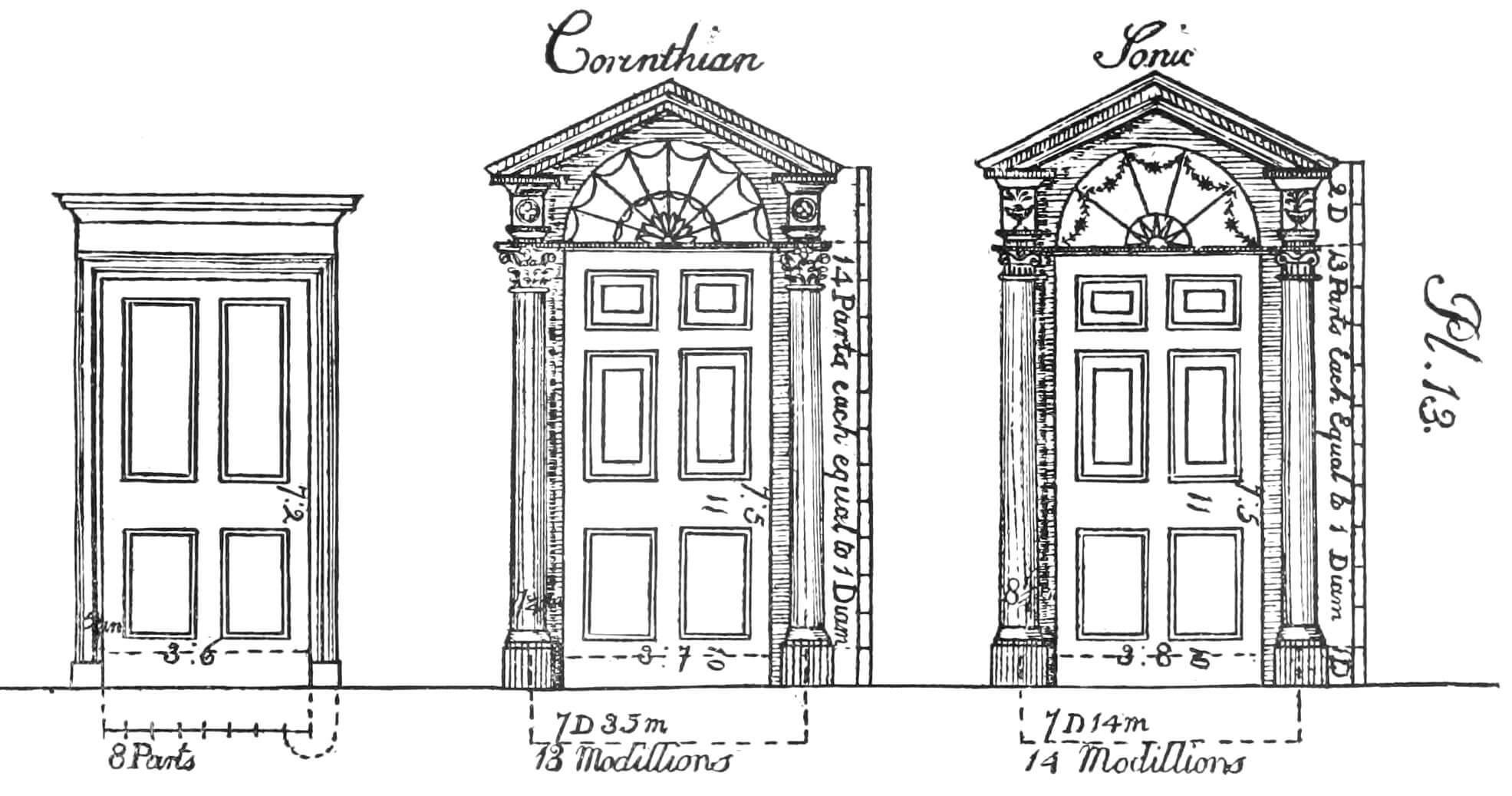

Builders guides imported from England were available here in the 18th century, but the first American guide is believed to be Asher Benjamin’s Country Builder’s Assistant published in 1797. The early guides were aimed at carpenters, providing them with exacting details on the ideal proportions and construction techniques for major elements such as columns, cornices, mantels, doors and windows. The builder’s guides published in the 1820s and 1830s, including some by Minard Lafever, an architect known in Brooklyn for his churches, did much to popularize the use of Greek Revival design details throughout the country.

The early builder’s guides occasionally included an elevation or floor plan for a commercial or residential structure, but they largely prioritized the technique of building over house design. True house pattern books, focused more on design and layout than construction, would become more common in the mid and late 19th century.

While hunting through some period architecture books we ran across full floor plans for two urban row houses by the same architect. Comparing them side-by-side yields some interesting perspective on changes to row house layouts over time. These plans are certainly not definitive — not every row house would have been designed to these specifications. However, they do give one architect’s vision for the practical layout of a city dwelling.

From New Jersey to Brooklyn.

The architect responsible for the plans was Robert Griffith Hatfield. Born in New Jersey around 1817, Hatfield apprenticed in an architect’s office and by the late 1840s established a practice in Manhattan with his brother Oliver Perry Hatfield. Over his roughly four decade-long career, he was best known for his larger commercial buildings and his engineering skills.

In 1850, he collaborated with James Bogardus on the Sun Building in Baltimore, considered one of the first significant cast-iron fronted buildings in the U.S, sadly destroyed by fire in 1904. Projects in New York includes the Seaman’s Savings Bank, the Knickerbocker Life Insurance building and the Institute for the Deaf and Dumb, all since demolished. Surviving buildings include warehouses in Lower Manhattan and flats on the Upper West Side. Hatfield was a founding member of the American Institute of Architects, serving as its treasurer for more than 20 years.

In 1844, under the name R. G. Hatfield, he published The American House-Carpenter: A Treatise on The Art of Building and The Strength of Materials. Hatfield’s book was typical of the others of the era; it was a guide for carpenters and builders on the basic craft of construction. Chapters focus on elements such as framing, doors, windows, moldings and stairs. He even managed to include a chapter on architectural styles. An 1844 review of the book in The New World called it “a practical book by a practical man.” Fortunately, part of that practicality meant including an elevation and full floor plans for a row house, along with notes on the ideal use of each space.

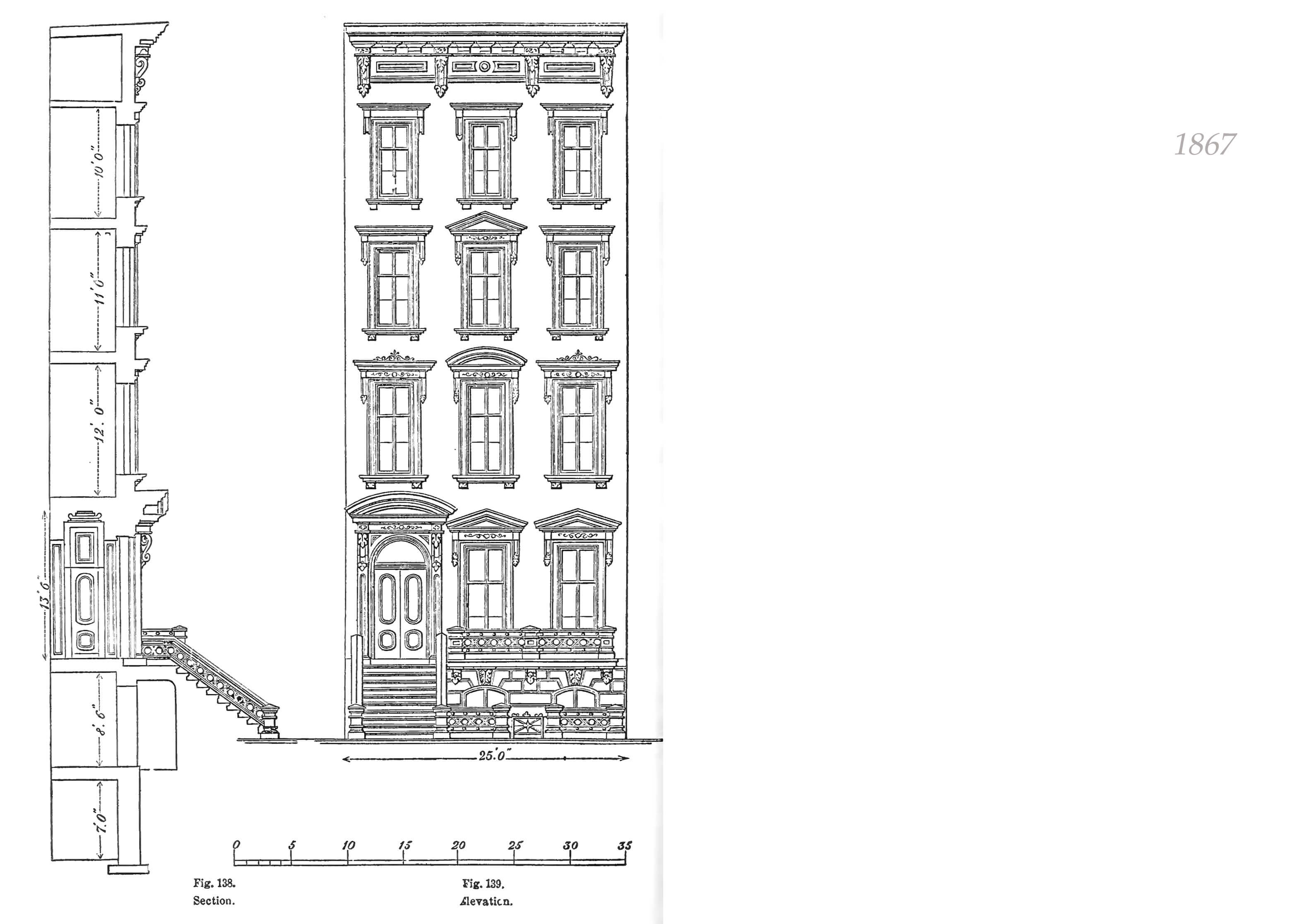

The book would be reprinted multiple times, with the twelfth and final edition appearing in 1892. Through all those editions, the row house plans included changed just once. From the first edition in 1844 until at least the seventh edition in 1867, the suggested design was a three-story Greek Revival-style structure with some hints of Italianate. By 1867, that design had changed to a four-story florid Italianate.

The later editions of the book appeared long after Hatfield’s death in 1879. He spent his final years in an early 1870s brownstone in Clinton Hill. Census records and city directories show that Robert and Charlotte Hatfield moved from Manhattan to Brooklyn around 1873, settling into the newly built house at 410 Grand Avenue. The house is one in a row of Italianates and while they are not known to be of Hatfield’s design, one hopes they were to his standards.

The 1844 Row House.

In the first edition of the book, Hatfield espoused the opinion that “every building should bear an expression suited to its destination.” For houses this meant something “neat and modest” with brick and stone preferred over wood and the imperative that houses be designed with the intended setting in mind. For a city house, he noted, a layout that might work for as a home for one family might be impractical for multiple dwellings.

The full plans included in the book focused on an “ordinary city house” for one family. While Hatfield acknowledged that most city lots were 25 feet wide, he noted that it had become common for “buildings of this class” to be reduced to 20 feet wide. He encouraged a restraint in ornamentation, suggesting that in a cornice “at least every alternate member should be left plain.”

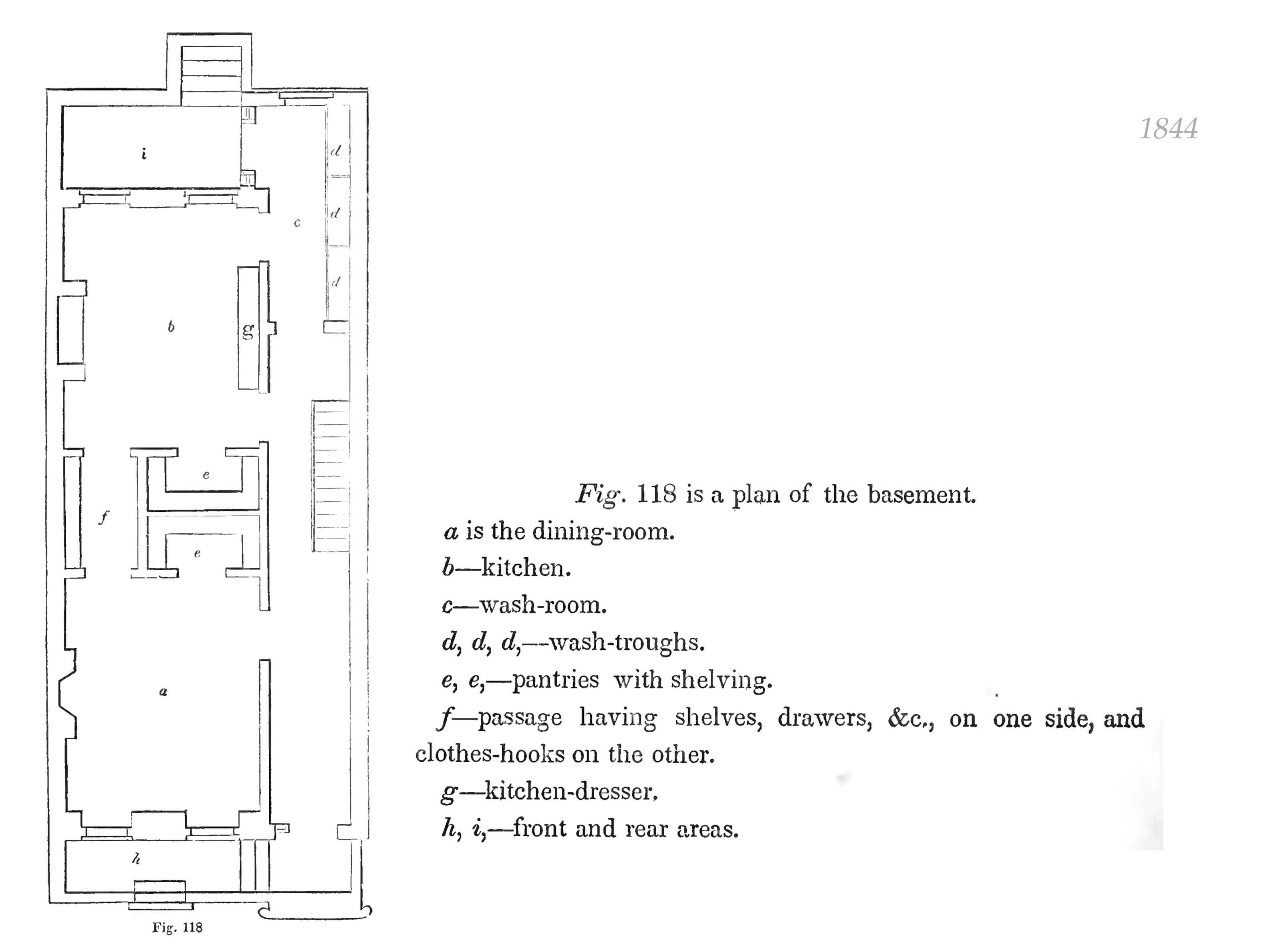

The basement plan includes a dining room in the front and a kitchen in the rear with an adjacent washing area.

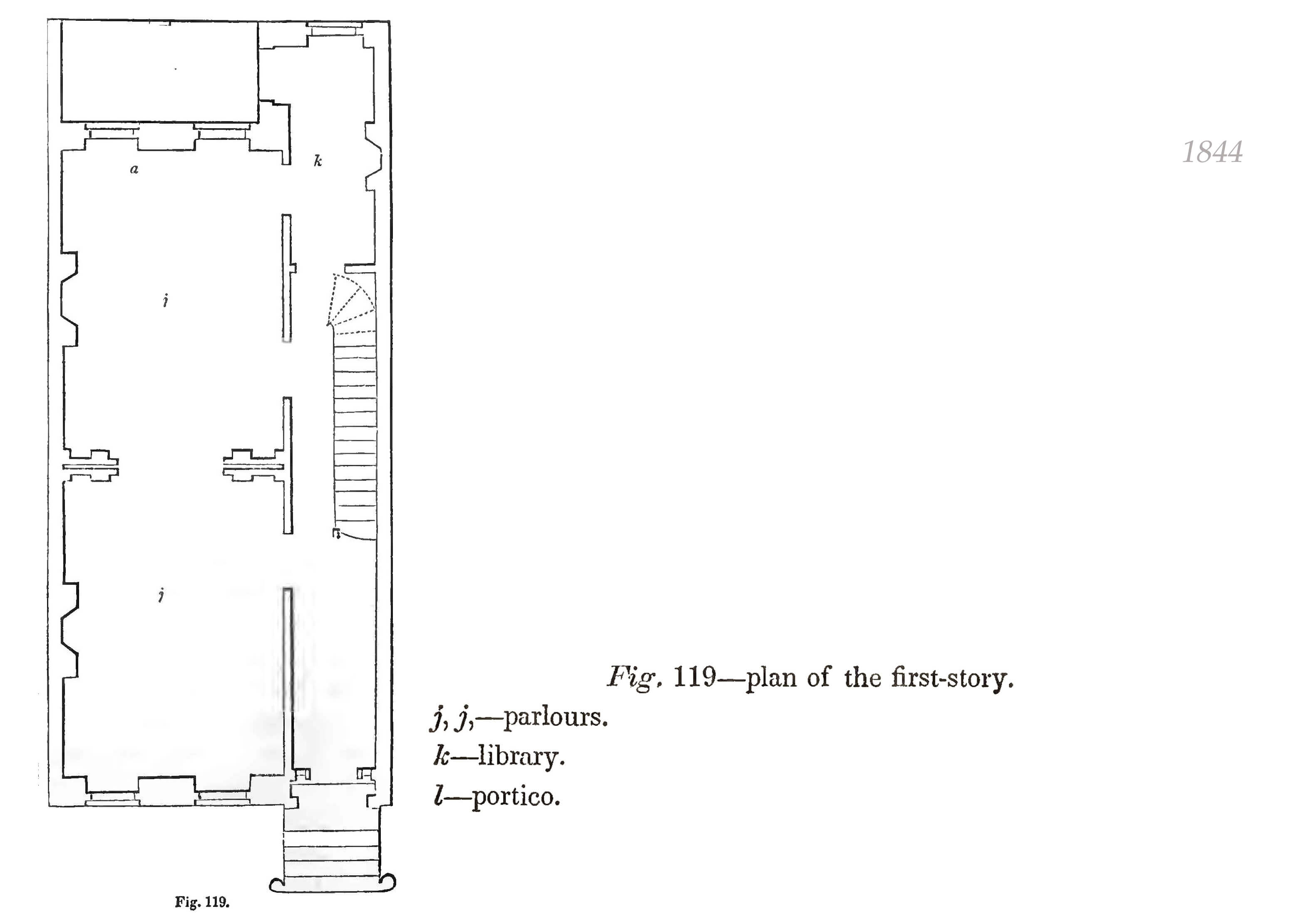

The first floor has double parlors, a library tucked behind the stair and a portico overlooking the rear garden (mislabeled as “a” rather than “l”).

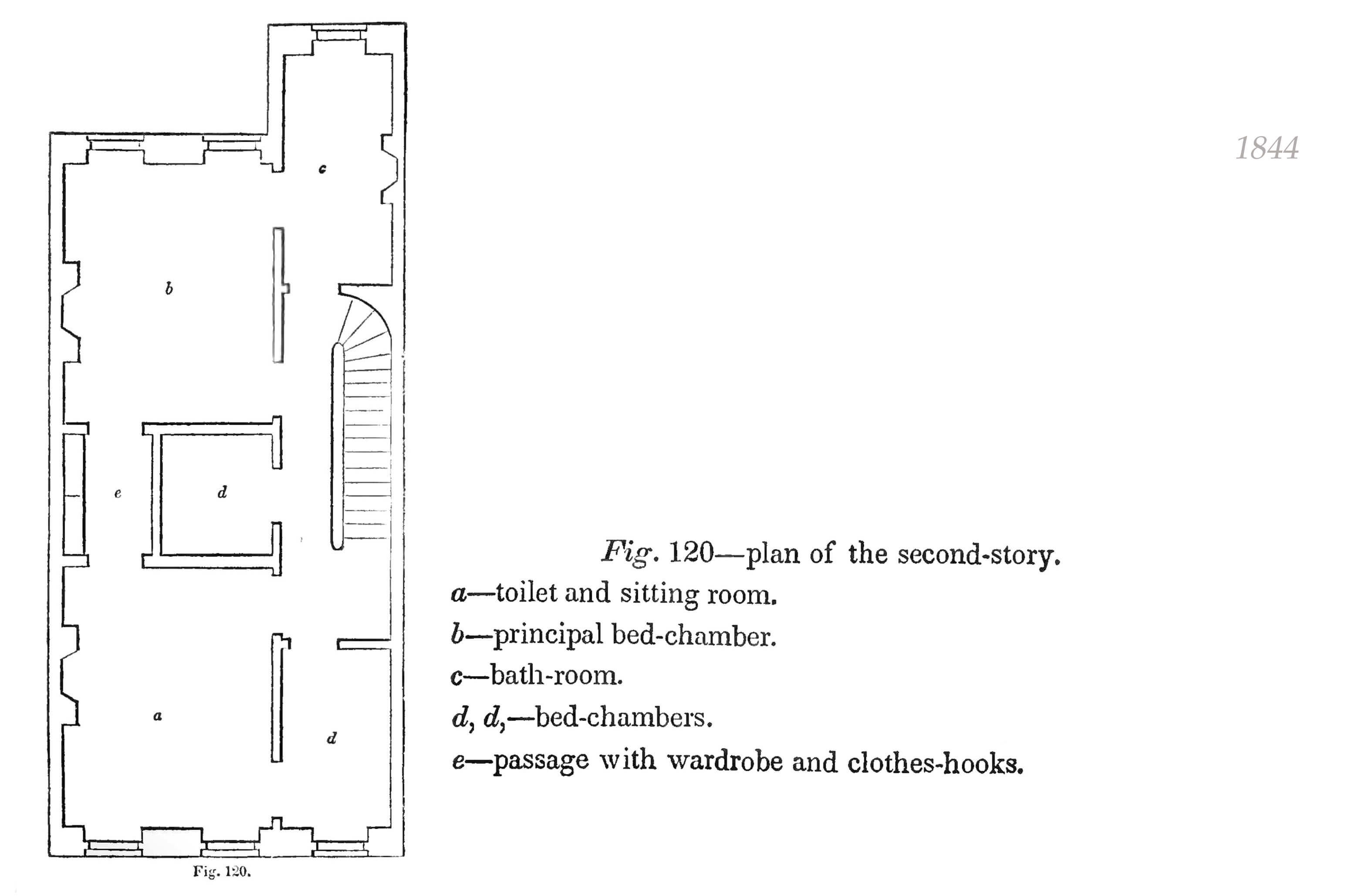

The main bedrooms are on the second floor, including one in the center without windows. A passageway between the main bedroom and front facing sitting room includes clothing storage. A bathroom is located at the rear of the floor.

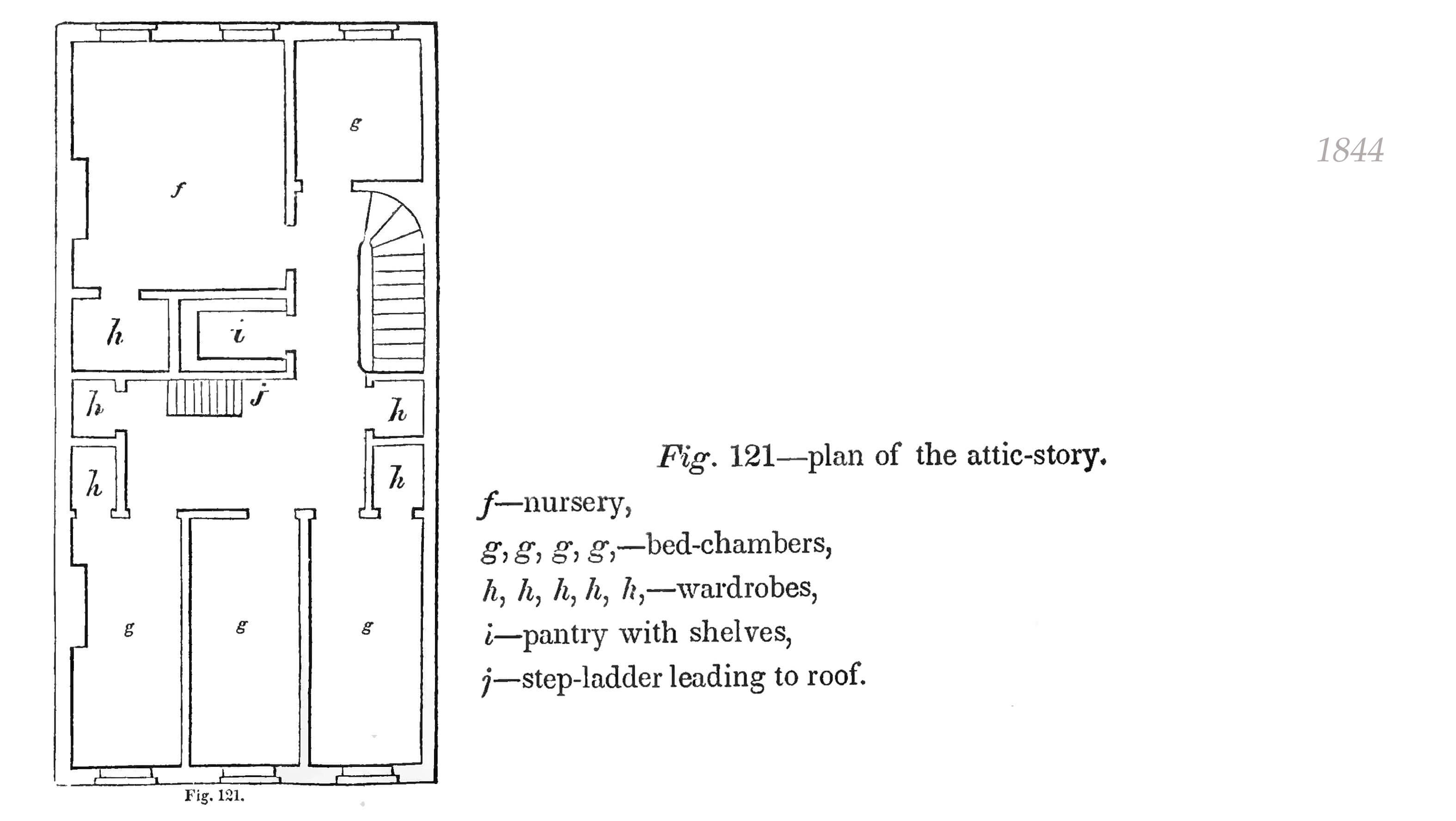

The attic story has additional bedrooms, storage and access to the roof.

The 1867 Row House.

While the language used to describe the design of the ideal residence didn’t change by the 1867 edition, the design of the “ordinary city house” certainly had. Gone were any remnants of restrained Greek Revival detail, replaced with a bold cornice, lintels both flat and pedimented and ornamental ironwork. This time the house was designed to take up the full 25 foot lot width and the height was increased to four stories.

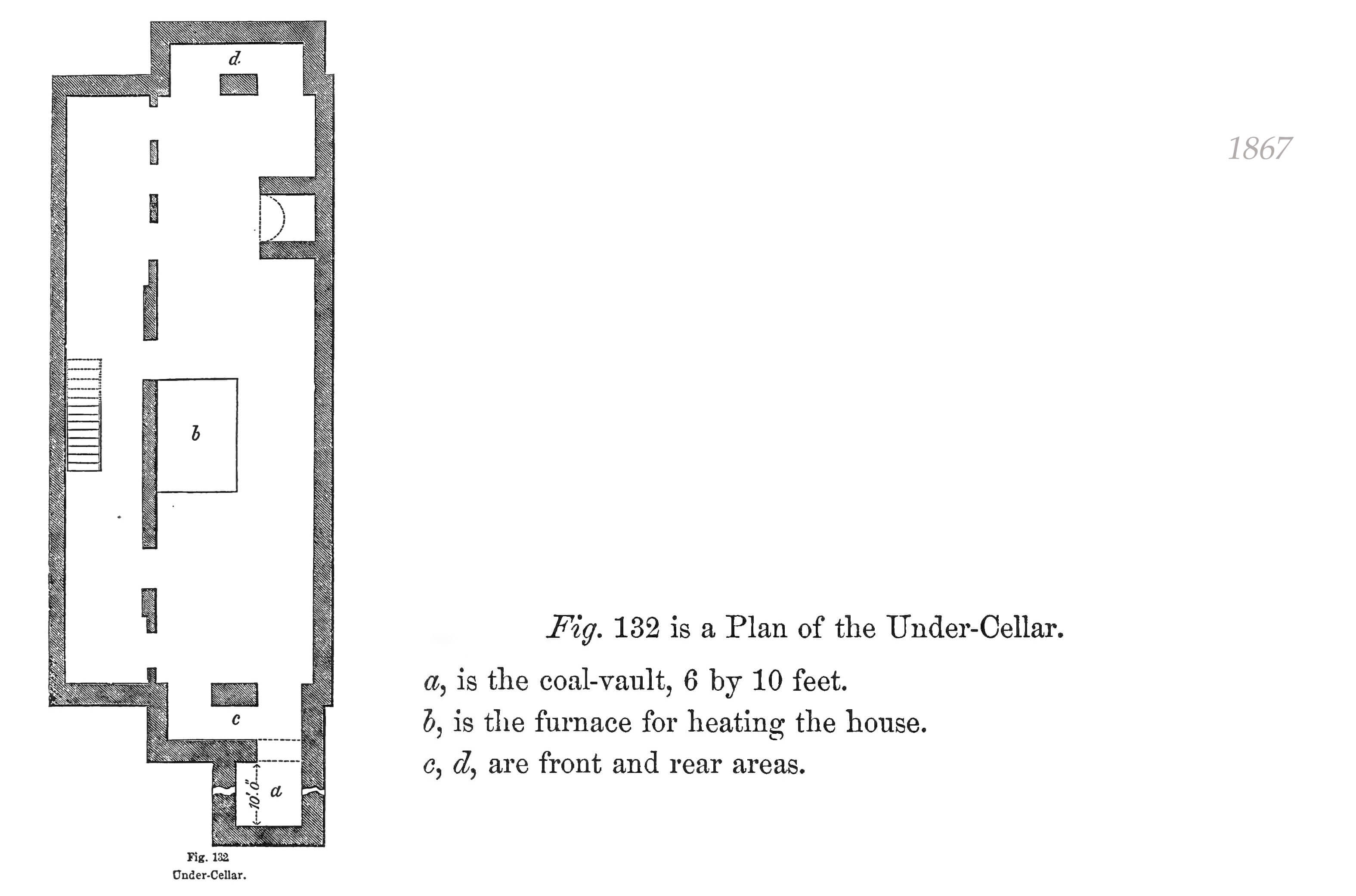

Unlike the earlier house, this plan includes both cellar and basement. The cellar includes a coal vault and space for a furnace.

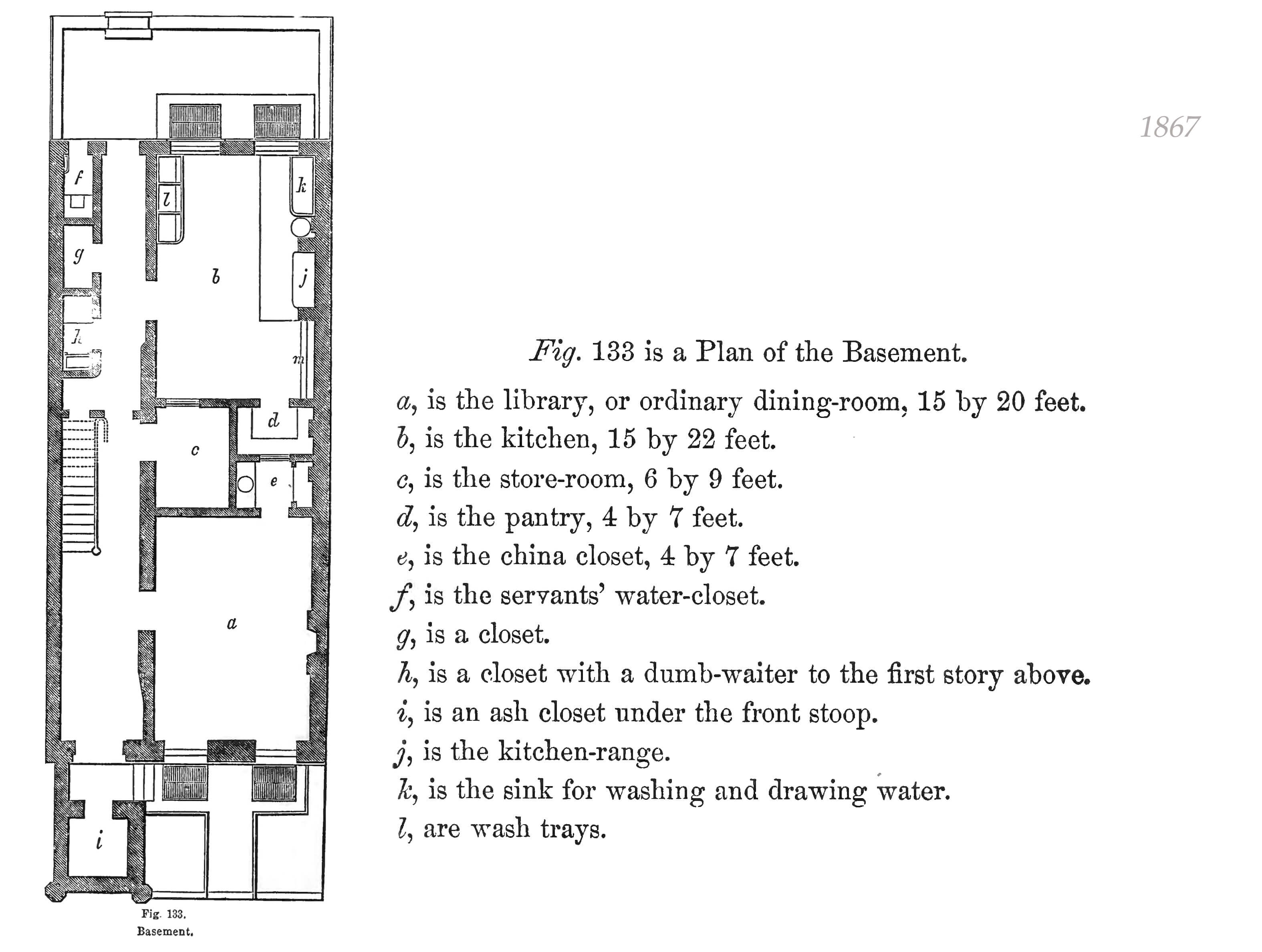

The front room of the basement level could serve as a library or “ordinary” dining room. The kitchen and service areas are still in the rear and a dumbwaiter is included.

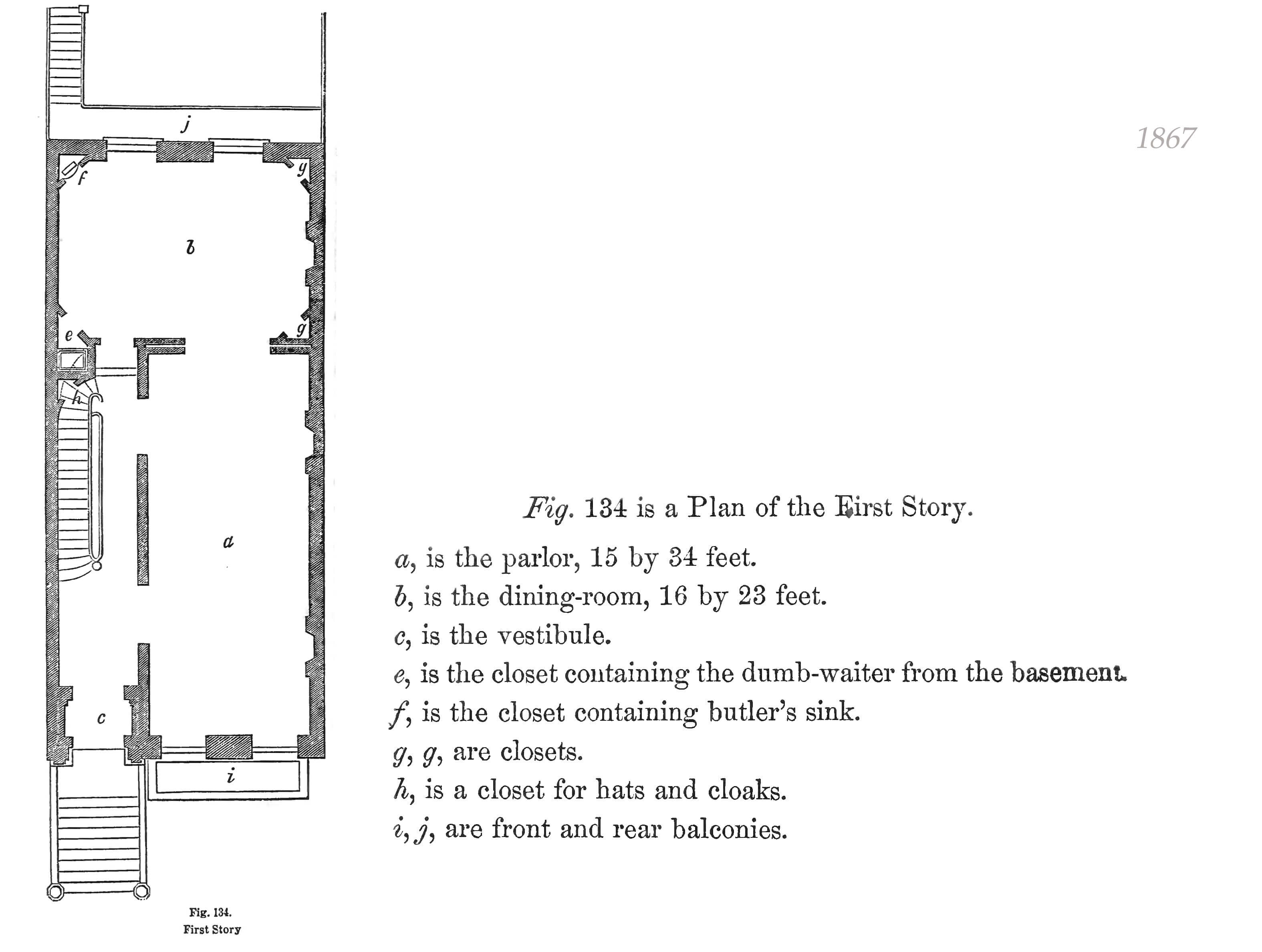

The addition of the dumbwaiter allows for the movement of the formal dining room from the basement to the parlor level. A small closet includes a butler’s sink for added convenience. The long parlor includes two fireplaces.

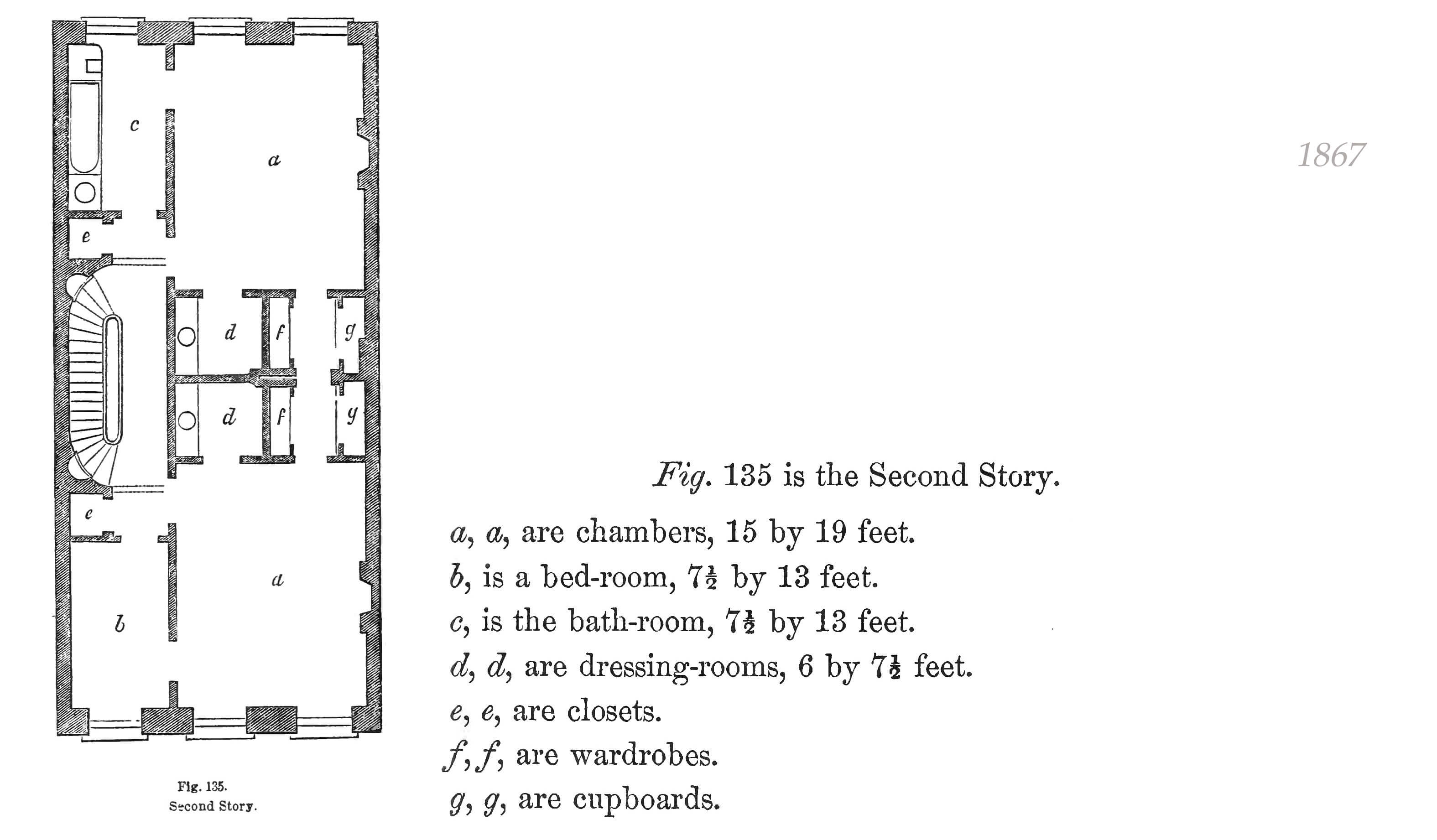

The two bedrooms of the second floor include dressing rooms with sinks and a passthrough with wardrobes. A full bathroom is located in the rear.

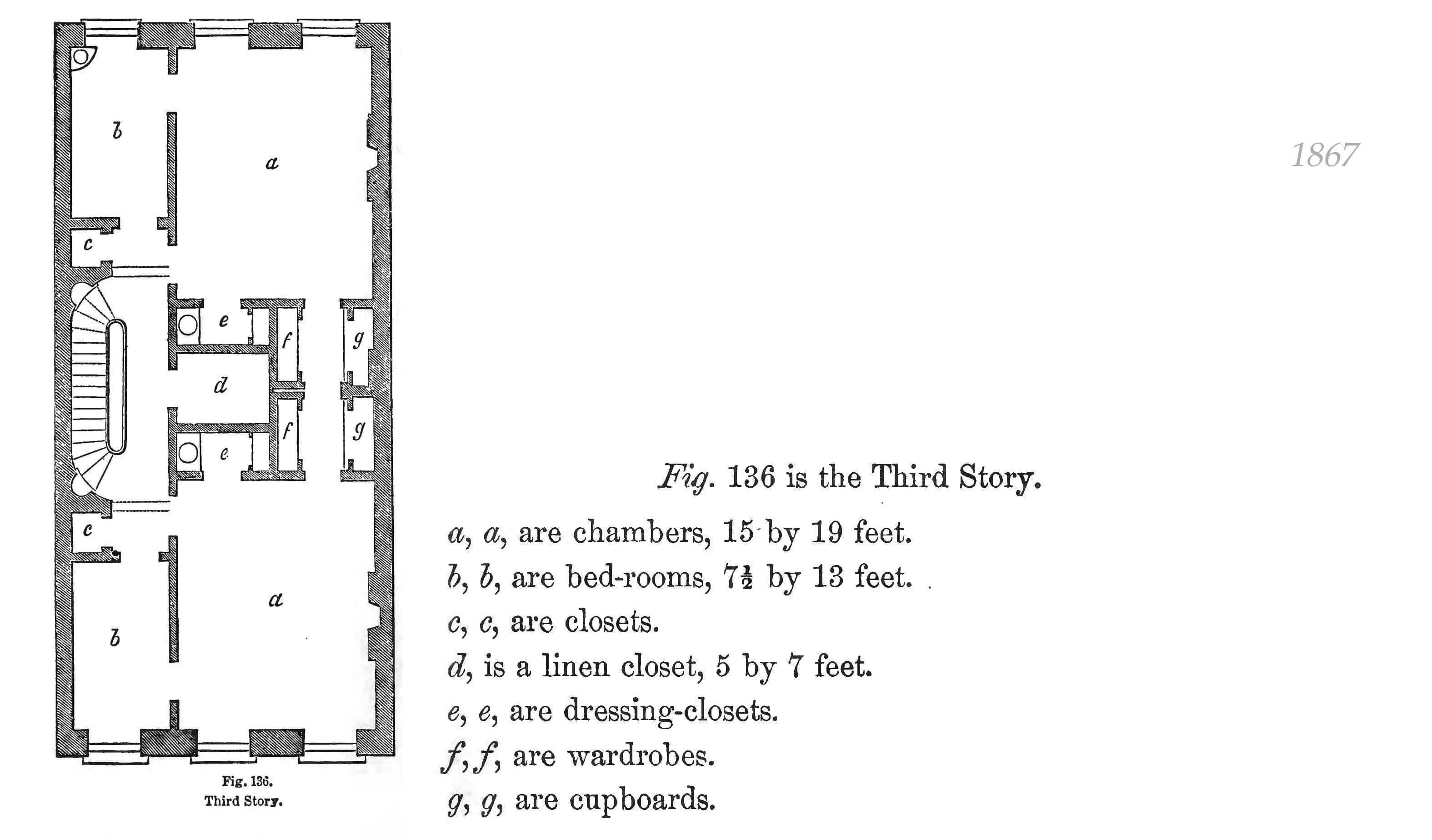

The layout is almost duplicated on the third floor but the bathroom has been eliminated in favor of an additional bedroom.

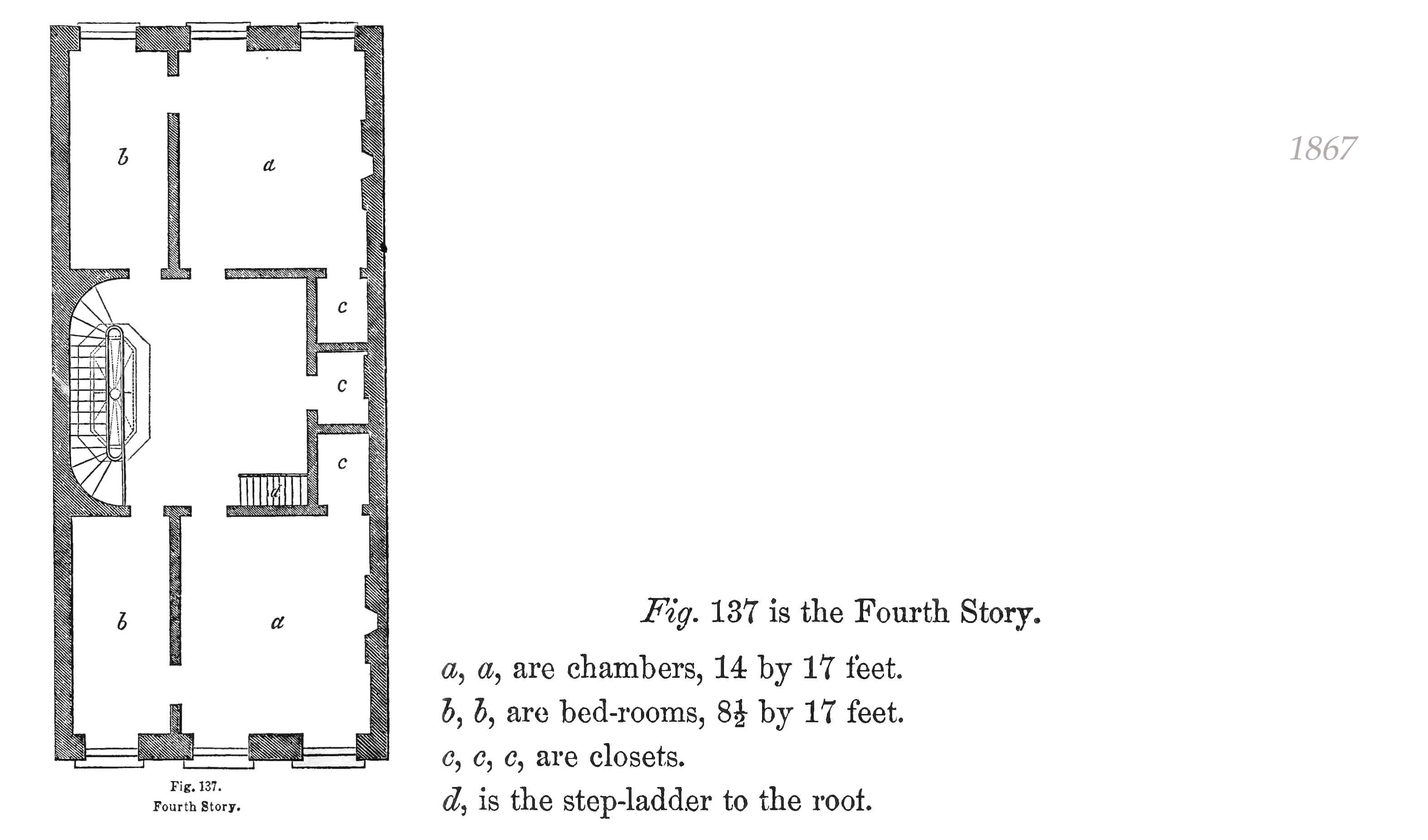

The top floor includes a simplified layout with bedrooms, storage and access to the roof.

If you want to check out Hatfield’s work in more detail many of the editions of The American House-Carpenter are available online along with his other publication, Theory of Transverse Strains and its Application on the Construction of Buildings.

[Elevations and floorplans by Robert G. Hatfield. Images via editions of The American House-Carpenter]

Related Stories

- Brownstone Bible Redux: Charles Lockwood’s Seminal New York Row House Book Gets an Update

- A Pattern Book-Perfect Second Empire in Rhinebeck

- Old House Lovers Will Drool Over These Vintage Architecture Trade Catalogs

Email tips@brownstoner.com with further comments, questions or tips. Follow Brownstoner on Twitter and Instagram, and like us on Facebook.

What's Your Take? Leave a Comment