Building of the Day: 5200 1st Avenue

Brooklyn, one building at a time. Name: Former Brooklyn Heights Railroad Company power house Address: 5200 1st Avenue Cross Streets: Corner 52nd Street Neighborhood: Sunset Park Year Built: 1892 Architectural Style: Rundbogenstil Romanesque Revival Architect: Unknown Landmarked: No The story: Public transportation has always been a necessary component of a vital and growing Brooklyn, and…

Brooklyn, one building at a time.

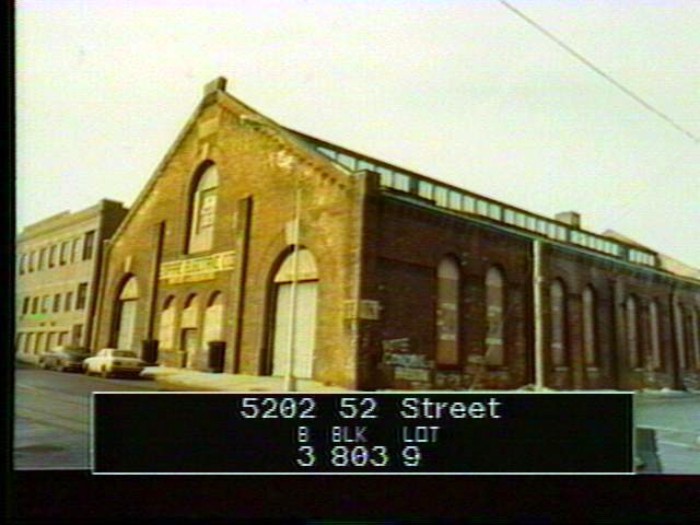

Name: Former Brooklyn Heights Railroad Company power house

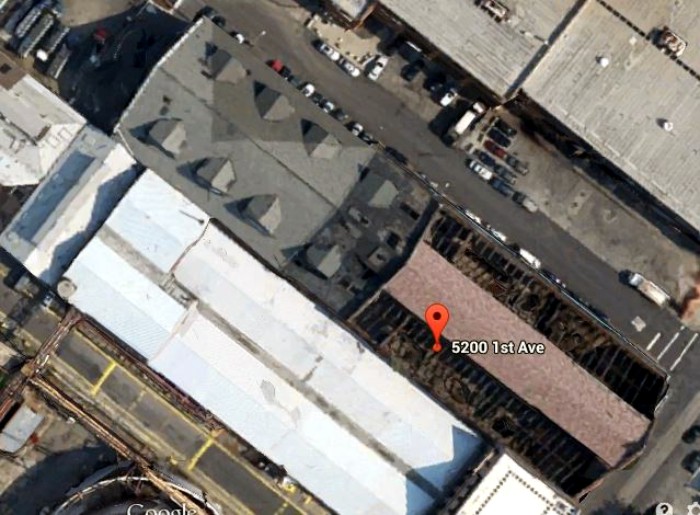

Address: 5200 1st Avenue

Cross Streets: Corner 52nd Street

Neighborhood: Sunset Park

Year Built: 1892

Architectural Style: Rundbogenstil Romanesque Revival

Architect: Unknown

Landmarked: No

The story: Public transportation has always been a necessary component of a vital and growing Brooklyn, and that was as true in the 19th century as it is today. By the end of the 19th century, the new elevated trains were being built all across the city, but below those tracks, the trolley car lines reigned supreme. They had more tracks, went along more streets, and connected parts of the city together that the elevated trains couldn’t or wouldn’t.

All of the transportation companies, whether ground or above, were all private companies. They were a broiling mass of competition, at times merging, breaking away, and then re-consolidating with each other, all in a battle for mastery over public transportation. One of the largest of these was the Brooklyn Heights Railroad Company. They had one of the largest systems of trolley lines in Brooklyn, and they were growing in leaps and bounds.

The company was founded in 1887, and began by running cable cars down Montague Street towards the Wall Street ferry. In 1891, they tested their first electric trolley car on Montague, and then began laying tracks wherever they could; expanding their routes and service area. Trolley car operations still run very much as they did when the system was invented. The cars run on tracks, powered by the electric current that passes through a pole and roller system that connects the car to the cable. The roller does just that, rolls along the live wires, delivering the current that powers the engine of the car.

The electricity needed to power the lines was generated from powerhouses. These were buildings placed in strategic places along the routes that made electricity and fed it to the lines. As can be imagined, this operation took a lot of power, which was all fueled by coal, so powerhouses tended to be next to water, whenever possible, in order for enormous amounts of coal to be easily delivered by boat or barge. Large quantities of water were also necessary to cool down the machinery.

Power houses were generally large, sprawling buildings, housing the two major parts of the power generating operation. Coal was fed into enormous boilers, producing steam energy and heat, and that was then passed through turbines engines that revolved at great speeds and converted the power into electricity. The two functions took place in two separate areas of the plant, and were architecturally configured differently as to purpose.

The Brooklyn Heights Railroad Company had several power houses along their many routes, in different neighborhoods. As they expanded into the Sunset Park area, they needed a local power house, and this one was built beginning in 1892. It’s a huge building, extending back over 240 feet, more than the length of an average city block. It’s 100 feet wide. The back end of it was near the waterfront, allowing for the coal deliveries to the boilers, and the front end, facing 1st Avenue, held the turbine engines.

Whereas the back of the powerhouse would have been dark, hot and crowded, with all of the boilers and equipment, the front end, housing the power generating turbines, was airy and light-filled, with clerestory windows above, allowing in light and air. The building was designed in the Rundbogenstil style of architecture, a German Romanesque Revival style that was extremely popular in Brooklyn, due in part to the many German American architects, like Theobald Engelhardt, who designed breweries, factories and warehouses across the city. The name means “round arched,” and that certainly fits this building, with its soaring arched windows. The running closed arched brickwork that forms a decorative cornice around the entire building is also typical of this style. It’s a beautiful late 19th century industrial building.

The Brooklyn Heights Railroad Co. had a very rocky history, but it, and its successors, generated power here until the 1930s, when buses began replacing trolleys. All of the equipment in the building was dismantled and removed, which must have been a herculean task. In 1950, the Empire Electric Company bought the building. They reconditioned electrical equipment, including transformers, and used the facility as a warehouse, as well.

Over the next half a century, PCBs and other serious poisonous contaminants leaked out of the transformers, and seeped into the bricks of the building, the ground and the ground water around it. The building has been found to also have VOCs; volatile organic compounds in the water collected around the building. The EPA sealed off the building, and bricked in the windows to prevent people from getting in or squatting there. The site is now a brownfield, and plans are in the offing to tear the structure down in order to treat the contamination.

The powerhouse is one of only a few remaining structures in the entire city built for this purpose. The most well-known and beautiful of these old transit power houses is the McKim, Mead & White power house on West 57th Street in Manhattan. That one is landmarked, and there have long been plans to repurpose that gorgeous and important building. This building survived because it’s in a remote location and it was being utilized all these years.

Unfortunately, the presence of PCBs in the bricks themselves has doomed it. I don’t know enough about how it all works to even know if it would be possible to contain or remove the contaminants, if someone was even so moved to do so. It’s very expensive, I do know that. The roof in the front is mostly gone, except for the clerestory windows. The maps are unclear, but I don’t see any demo permits, so as far as I know, the building is still standing. GMAP

(Photo: Kate Leonova for PropertyShark, 2007)

What's Your Take? Leave a Comment