Walkabout: It’s Nice to Be Ice, Part 4

Read Part 1, Part 2, and Part 3 of this story. In 1901, Brooklyn’s favorite son, Seth Low, took office as the second mayor of Greater New York City. He replaced disgraced Tammany Hall front man Robert Van Wyck, who had been elected to office in 1897, and began his term with the newly consolidated New…

Read Part 1, Part 2, and Part 3 of this story.

In 1901, Brooklyn’s favorite son, Seth Low, took office as the second mayor of Greater New York City. He replaced disgraced Tammany Hall front man Robert Van Wyck, who had been elected to office in 1897, and began his term with the newly consolidated New York City on January 1, 1998.

Van Wyck might have been re-elected, especially with Tammany Hall help, except for the scandal that brought down his administration – the Great Ice Scandal of 1900.

The story of the importance of the ice trade, the power of the American Ice Company and the scandal that almost brought a city down have all been related in Part One, Part Two, and Part Three of our series here. Today’s conclusion will wrap up what happened to the major players in this grand opera of New York City business and politics.

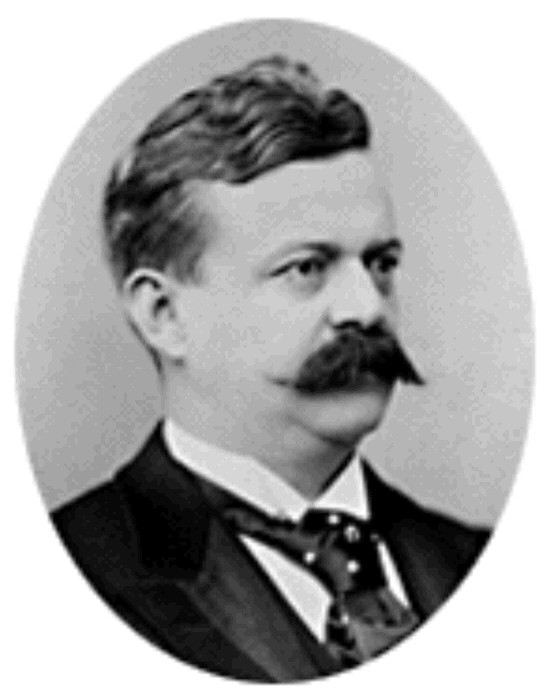

The American Ice Company was led by Charles W. Morse, a cutthroat businessman, and veteran of the natural ice business. He had started in his home state of Maine in the shipping business.

Over the course of less than ten years, between 1890 and 1900, he managed to buy up just about all of the ice companies in the New York City area, becoming a monopoly- the city’s only source for life sustaining ice used in businesses and homes, both high and low. Controlling ice in the days before electric refrigeration was controlling the health and well-being of everyone in the city.

In the spring of 1900, Morse exerted that control and doubled the cost of ice in the city and suburbs. He cited shortages, but there were actually surpluses after an exceptionally cold winter.

Morse was in business with Tammany Hall, and their people controlled the docks and piers, so no ice from any other ice companies was allowed to land at a New York dock. The Tammany men were not above knocking a few heads together or vandalizing a few boats and equipment to get their point across.

NYC was off limits to all ice men, except those working for the American Ice Company.

The top tier of men in Tammany Hall, including Richard Croker, boss of bosses, his immediate subordinates, and Hugh McLaughlin, boss of Brooklyn, all had hundreds of thousands of dollars in American Ice Company stock.

When Morse made money, they made money, even though the people suffering the most in this crisis were the poor and immigrant populations in the tenements who could barely afford ice as it was, let alone the doubled price.

These people looked to Tammany as the friend of the people, and thought Tammany would protect their interests, and they had all voted accordingly. They had no idea that Tammany’s first interest was to protect and enrich itself; on their constituents’ backs, if need be.

Mayor Van Wyck also had over half a million dollars in AIC stock, and had been a guest of Charles Morse at his Maine home, and had toured the ice fields and factories with him. He was bought and paid for.

As the ice crisis went on, and Morse tripled prices, an investigative press and Van Wyck’s political opposition found out about Van Wyck’s stock and Tammany’s leader’s involvement in the crisis.

The subsequent backlash, hearings and investigations caused Morse to drop his prices, Tammany had to sacrifice some people and power, and Robert Van Wyck’s political career was over. So what happened to everyone next?

As the new 20th century progressed, so too did advances in making chemically produced plant ice. Factory made ice, and the technology of refrigeration were making river ice less necessary. On top of that, rumors about the cleanliness of Hudson River ice began circulating.

The river was being polluted by industry, and rumor had it that New York’s bouts of typhoid were caused by germs in the ice. The ice industry tried to quell the rumors, but it was too late. The public was getting suspicious of natural ice.

In 1910, the American Ice Company’s top facility at Iceboro, Maine burned to the ground, taking with it many of the company’s schooners that were used to deliver ice.

It was a blow that crippled the company in Maine, one of the last remaining “safe” ice fields, as far as the public was concerned. The operation that had ruled ice in New York City was down for the count.

As usually happens, the main players in the scandal all made out like bandits. Former Mayor Robert Van Wyck not only had the Ice Scandal to contend with, there were other allegations of corruption during his tenure.

He was at the center of another scandal called the Ramapo Water Steal, which involved a dummy company called the Ramapo Water Company and a sweetheart city contract for millions of dollars for them to supply water to NYC. The public outcry on this one caused the State Legislature to meet to pass laws to revoke the contract.

Van Wyck also publically supported Police Chief “Big Bill” Devery, who was known to be leading a corrupt police department in vice and crime. He called Devery “the best police chief New York ever had.”

When the evidence the Chief was one of the biggest criminals the city ever had, Van Wyck did not look good. The decent folk of the city gave a great sigh of relief when he was finally voted out of office.

Taking it all in stride, Van Wyck, a life-long bachelor and man about town, suddenly got married. The day after he left office, he and his wife moved to Paris. He told his friends and enemies alike he was never coming back, and was going to take it easy.

He certainly had the money to do so. Never a wealthy man before taking office, he now had five million dollars in his new European bank account.

Today, that would have been around $74 million. He lived in Paris for the rest of his life. He only returned when his body was brought back for burial in Woodlawn Cemetery, in 1918. Who said you can’t get rich in politics?

Richard Croker, the boss of bosses at Tammany Hall, was never the same after the Ice Scandal. In 1900, he failed to bring William Jennings Bryan a Democratic victory in New York City during the presidential election.

In 1901, Tammany’s candidate for mayor was defeated by Seth Low, and Croker decided that it was time to retire. The Irish-born son of a dirt poor Protestant land manager who had immigrated to New York when Croker was only two, Richard Croker decided to go back to the Old Country.

He now had millions of dollars gathered from years of bribery, graft and extortion for Tammany Hall, so he bought an estate in Ireland and became a country gentleman farmer, raising race horses and prize bulldogs.

Croker had been married and divorced, and had four adult children. After his retirement, Croker remarried at the age of 71. He and his new wife had his real estate holdings, including a $2MM estate in Palm Beach put in both their names.

The children sued to get control of the estate, citing incompetence, but lost. Mr. and Mrs. Croker retired to his new home, Castle Glencairn, near Dublin. One of his horses won the Derby, and he was the first man to be on record for paying $5,000 for a champion bulldog.

At the age of 80, Croker caught a bad cold after being out in inclement weather, and it worsened. The ex-gang member, prize fighter, alderman, city coroner, feared Tammany Hall chief, and retired lord of the manor died of that cold on April 29th, 1922.

Richard Croker’s children shouldn’t have messed with the boss of bosses. When he died, he purposely left no will, and his children never got a dime of his fortune. They sued, to no avail. The new Mrs. Croker got it all.

And the Ice King, Charles W. Morse? He also proved that crime does indeed pay. Oh boy, did it ever pay. After the great Ice Company Scandal, Charles Morse decided to get out of the business before he was prosecuted. He sold his company stock and broke up the trust back into smaller companies.

He managed to make a nice $12 million profit in the process. Today, that would be around $312 million. Morse too, felt the stirrings of marital bliss, and also found himself a new wife.

His first wife had died in 1897. In 1901 he married a divorcee named Clemence Dodge. They lived at 724 Fifth Avenue, with a summer home in Bath, Maine, Charles’ home town.

Most men would be happy with the fortune and would, like Van Wyck and Croker, retire and live well off their ill-gotten gains. But Charles Morse was different.

Twelve million dollars wasn’t nearly enough for him. He still had his most adventurous years and deeds before him. I’ll finish his tale next time, bringing back Brooklyn people and events that I’ve written about before.

Everyone comes together in the effort to control great power and fortune, as the financial life of the nation hangs in the balance. This guy was a piece of work! But that’s another story all together, and no longer a part of the great ice monopoly.

Natural ice had a slight comeback during World War One, but by the mid-1920s, the industry was in its death throes. By the 1930s, most Americans had been won over by advances in refrigeration, and the home refrigerator had replaced the ice-box for all but the poorest Americans.

Industrial refrigeration had replaced ice in meat packing, produce, milk, medicine and other industrial use. Ice could now be made in factories that was as hard and pure as any taken from a fresh water pond.

Restaurants and hotels dispensed ice cubes in the new mixed drinks, and the modern age of ice and refrigeration was in full swing. The ice houses along the Hudson and the rivers of Maine and New York fell into disrepair, were repurposed, or torn down.

By the end of the 20th century, river ice, the substance whose price had brought the greatest city to its knees, was only used now to occasionally make ice sculptures. One of the 19th and early 20th century’s biggest and most lucrative industries had just melted away.

(Young women delivering ice in 1918. Wikipedia)

What's Your Take? Leave a Comment