Walkabout: Kate Mullany: A Troy Story, Part 2

Read Part 1 of this story. By 1864, the detachable shirt collar and cuffs were making Troy, N.Y., one of the wealthiest cities in America. A simple convenience, first conceived by a Troy woman – attaching a separate collar and cuffs onto a shirt by means of buttons, had caused a revolution in men’s clothing….

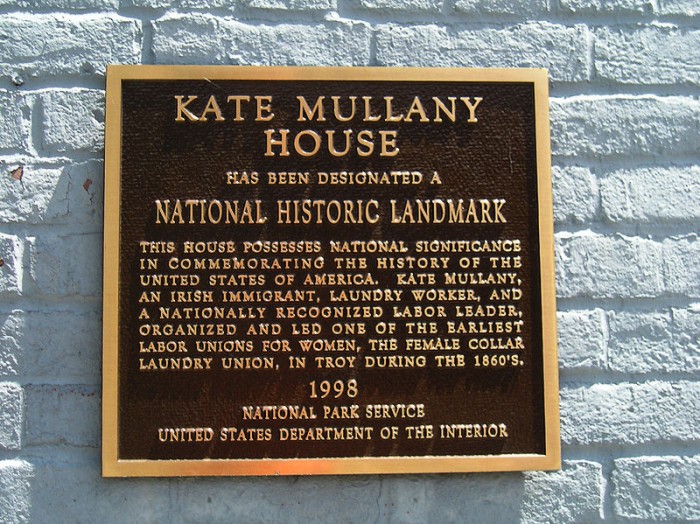

350 8th Street, Kate Mullany House, Troy

Read Part 1 of this story.

By 1864, the detachable shirt collar and cuffs were making Troy, N.Y., one of the wealthiest cities in America. A simple convenience, first conceived by a Troy woman – attaching a separate collar and cuffs onto a shirt by means of buttons, had caused a revolution in men’s clothing. It was really quite amazing, and as the demand for detachable collars grew, so too did the facilities to make them. Cutting rooms, sewing factories and laundries – all were necessary to making the thousands of collars that would give Troy the nickname “The Collar City.”

Troy’s garment factories and laundries made their owners among the richest men in the city, with fine homes, and the best of everything. The thousands of workers who worked in those factories were not as fortunate. While conditions in the factories were certainly not great, nothing was as bad as the conditions in the laundries. Here women, and it was almost all women, toiled for 12 to 14 hours a day, no matter what the season, in incredibly hot, humid laundries, working with boiling water, caustic bleaches and starches, and red hot irons. They washed, bleached, starched and ironed millions of collars, enduring back pain, aching feet, burned limbs, scalding and chemical burns for $3 or $4 a week.

Almost all of the women who worked in the factories, laundries and mills were Irish. They had come to America during the great migration of the Irish during the Potato Famine, and made their way upstate from New York City and Boston because there was plenty of work in Troy and the surrounding mill towns. The Irish helped build Troy. Her iron and steel works in the southern part of the city employed many of the men, while the textile industry employed both men and women, with women the main workers in the sewing and laundry factories.

One of these workers was a young girl named Katherine Mullany. Her story began in the first part of our story, last time. In 1864, she was 19, and the only breadwinner in the family. Her family emigrated from Ireland to America in 1850, and they moved to Troy in 1853. In 1864, Kate’s father died, and her mother became sickly, leaving Kate, as the eldest child, to be the family’s sole provider. She got a job in a collar laundry, the highest paying of the garment industry jobs, but also the hardest.

The collar laundresses had asked management for higher wages, but they were ignored. Well, not totally ignored. The commercial laundries had all installed new starch machines that could run the collars through a starch bath much faster than human hands. The machine increased production, but also make the women on the other end of the process work much harder to keep up with the machine. The scalding water from the machine had burned many of the women working with it, and the increased production was causing the pressers to burn themselves and the collars trying to keep up. Any collar ruined was docked from their pay.

Kate Mullany had been listening to the men in her building and neighborhood talk about their success in forming an Iron Molder’s Union for their jobs in the steel mills. After an initial struggle, they had been able to successfully bargain for improved work conditions and higher wages. She talked with them about organizing a women’s laundry union, and the men were encouraging. With conditions worsening in the laundries, and no pay raises in sight, Kate decided that someone had to do something, and that person had to be her.

With the help of her co-worker Esther Keegan, Kate Mullany decided to organize the female laundresses into a union. On February 23, 1864, the three hundred women who signed up as the Collar Laundry Union walked out of all of the fourteen commercial laundries in Troy. The strike was on.

Working 12 to 14 hours a day doesn’t give one much time to organize anything, but because Kate’s siblings took care of the house and younger children, she was able to put together this massive undertaking in a time before telephones, automobiles and computers. Many of her fellow workers had to take care of home and family as well as work. Even so, organizing the strike took planning and a forceful personality. It also was risky. In spite of the difficulty of the work, and the horrible conditions, the laundress jobs were the highest paid female workers, and if the strikers lost their jobs, there were plenty of desperate women ready to replace them.

That’s what the owners of the laundries counted on, but they were not ready for Kate and her union sisters. The union demanded a 20 to 25 percent wage increase and they wanted something done about the scalding starching machines. The owners told them they couldn’t afford to pay the women more money unless the costs were passed on to the collar manufacturers. But the women stayed out of the laundries, and by February 28, a few of the owners had caved. The next day, the rest of them capitulated as well. The strike was a success.

Kate and her fellow organizers knew that their work would come to naught if the union did not continue. It couldn’t be a onetime event, and they needed to become a fixture in Troy’s labor movement. Because they had been helped and encouraged by the Troy Iron Molders, the women presented the Iron Molders union a large embroidered banner at their annual picnic on July 18, 1864. The presentation was from the Collar Laundry Union of Troy to the Iron Molders’ Association. This helped to solidify their legitimacy as a permanent labor union, recognized by other unions. This was very important.

Two years later, in 1866, Kate’s union donated $1,000 to the Molder’ Great Lock Out. This was also positively received by the public and the press, and the Collar Laundry Union was invited to join the Troy Trades’ Assembly. That year, after another short strike, the wages of the members increased from $8 to $14 a week. Kate Mullany and her fellow union officers demonstrated their good business sense, accumulating a larger treasury than most of the men’s unions, offering their membership benefits during sickness and family death, something unheard of before the union.

In spite of the Collar Laundry Union’s successes, there was still resistance to women in the labor movement by some men. Women who had tried to organize in other industries and other cities had not had the same success as in Troy. The CLU found itself in the position of leadership and mentorship to other women’s unions, even to the point of paying their expenses while union leadership was trained. In this way, Kate Mullany became not just an important figure in Troy’s labor movement, but in the labor movement of the United States.

In September of 1868, Kate attended the National Labor Congress in New York City, where she was nominated for the position of second vice president. She was elected, but declined the position because the first VP was also from New York State. She went home to Troy, and continued to work for better conditions for her workers.

After living in three different rented homes in various parts of Troy since arriving there in 1853, the Mullany family was finally able to buy a home. Kate bought a three-story, double row house located at 350 8th Street. The family was able to live in one of the houses and rent the rest out. Kate was proud to be able to afford a decent house, and the family lived there until 1875.

In 1869, the union organized another strike, but this time, the laundries and the collar manufacturers vowed to fight to break the union. The ladies had the support of the male Iron Molders’ Union, which opened their hall to the CLU, and donated $500 a week to them. A huge rally was held, with 7,000 people attending, including many of the merchants and professional people of Troy, who were sympathetic to their cause.

The collar manufacturers refused to send work to any laundry with union workers. They even helped laundry owners hire and train new laundry workers. The CLU countered by establishing a cooperative laundry, but it failed. The laundries went to the papers and vilified the Union and its leadership. They offered to hire striking workers at a higher wage, if they would give up union membership. One manufacturer even established a laundry in New York City.

The CLU decided to form the Union Line Collar and Cuff Manufactory. Kate was appointed president. They sold shares for $5, and were ready to offer interest after the factory started up. They got the stamp of approval of a large New York state trade union organization, and were thrilled that the NYC retail giant, A. T. Stewart, promised to buy the collars produced by the new company. The CLU thought they would succeed.

But the manufacturers were too powerful. They announced they were putting a new paper collar on the market, eliminating the need for laundries. The sale of the Union Line Collars dropped, and the Iron Molders’ Union had to stop financial assistance. In 1870, Kate and her officers dissolved the Collar Laundry Union. All of its members, except the officers, went back to work at their old jobs and their pre-strike wages.

The Collar Laundry Union had lasted twice as long as any other woman’s union and paved the way for other women’s unions in the garment industry.Although they had been broken, other unions would succeed. Kate and others remained in the labor movement, a part of a cooperative of women’s unions. Kate was a member of the Starchers Union. She also got married, to John Fogarty.

The Troy factories grew, as did the collar industry. By the turn of the 20th century, women’s fashions had also embraced the detachable collar, expanding the industry even further. Troy’s prominence as the “Collar City” remained. The shirt and garment factories on the Troy waterfront were in operation until the 1950s, and were Troy’s largest employers. Today, to my knowledge, Troy has only one active garment factory still operating.

Kate Mullany died in 1906. In 1998, her home at 350 8th Street was declared a National Historic Landmark, and was visted by First Lady Hillary Clinton in 2000, when Kate was inducted into the National Women’s Hall of Fame. A bill to designate the house as a National Historic Site had been introduced by Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan, but got mired down in Congressional inaction. When Hillary Clinton became a senator, she took the bill up again, and it was passed. The house has been a National Historic Site since 2008. The house is also on the Women’s Heritage Trail. It is perhaps quite ironic that the house is only a block away from the Collar City Bridge. GMAP

What's Your Take? Leave a Comment