Walkabout: Machinations at the Mechanics Bank, Part 2

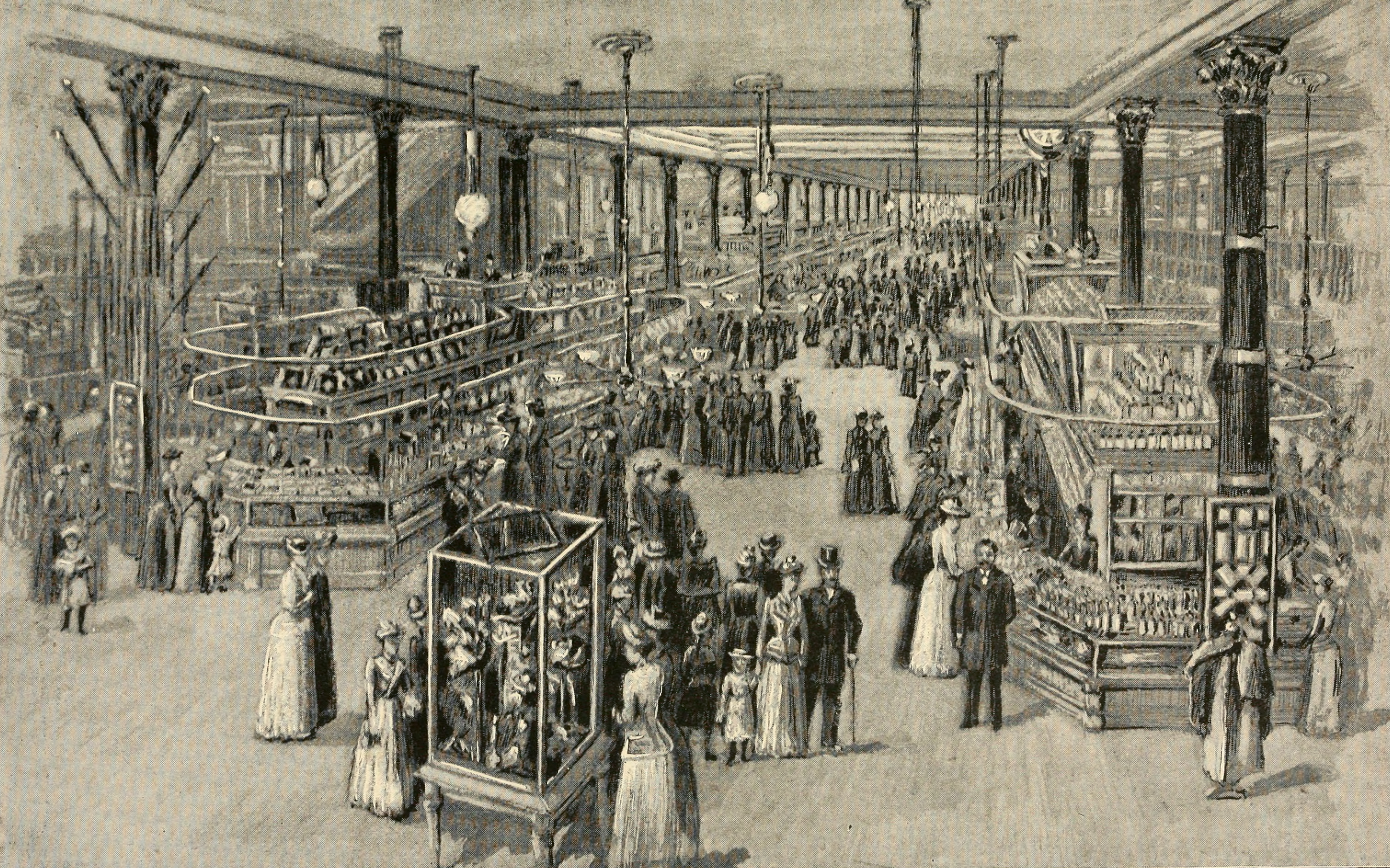

Union Bank, Temple Bar Building, Court Street. 1908. Photo: New York Public Library. Mr. David A. Sullivan, Esq. was president of the Union Bank of Brooklyn, at the turn of the 20th century. In 1906, his bank merged with the Mechanics and Traders Bank of Manhattan, which had no connection to the Brooklyn bank of…

Union Bank, Temple Bar Building, Court Street. 1908. Photo: New York Public Library.

Mr. David A. Sullivan, Esq. was president of the Union Bank of Brooklyn, at the turn of the 20th century. In 1906, his bank merged with the Mechanics and Traders Bank of Manhattan, which had no connection to the Brooklyn bank of the same name. The Union Bank had headquarters at 44 Court Street, and nine branches across Brooklyn, and was a substantial sized Brooklyn bank with several million dollars in assets. The Manhattan-based Mechanics Bank was a member of the Clearing House Association, a consortium that had been buying up smaller, independent banks, and was quite solvent, itself. In fact, Mechanics’ activities had convinced the interests behind Union Bank to acquire it, as they seemed to be on a similar business track. David Sullivan became head of both banks, a powerful position for any man, and one that probably paid him quite well, and gave him social standing for himself and his family. Too bad it wasn’t enough.

The economy was in a panic in 1907, one of several “Panics” that seem to be cyclical, the same then, as now. But back then, there was no such entity as the FDIC, and when the populace sensed their hard-earned money, supposedly sitting in the bank, was not there, or that their bank was mismanaging it, there were runs on the banks, and people emptied out their accounts. Money, as we all know, rarely simply sits in a vault, it is spent on loans and other transactions designed to return even more money to the coffers. A serious run on a bank could cause it to close, and in the Panic of ’07, a run on the Mechanics and Traders Bank on Broadway and Broome Street almost did just that. Fortunately for them, disaster was averted by paying out those who wanted their money, and funds were borrowed from other banks to make up any shortages. The bank heaved a large, collective sigh of relief.

But over a year later, in 1908, the rumors started that there was funny business going on with the books at the Mechanics Bank. David Sullivan was no longer president of either Union or Mechanics at that time, having returned to his private practice of law. It turned out that Mr. Sullivan had been “looking at the books” in 1907. Not uncommon for a bank president, except that he was looking at them in the middle of the night, behind closed doors, the night before the State Banking official was supposed to examine those same books. An investigation followed, a Grand Jury empaneled, testimony heard, but the whole thing was suddenly and inexplicably dropped.

In 1910, Union Bank collapsed, the Brooklyn-based institution citing the acquisition of Mechanics and Traders as the reason for the failure. They claimed that Mechanics brought with it far too much debt, that 75% of its loans were paying “slow”, if at all, and too high a percentage of those loans were going into default. “Brooklyn real estate was dead,” the bank said, and was not coming back from the Panic of ’07 fast enough. Union had enough funds to pay all of its customers, but not enough money to operate, and the bank, a fixture in Brooklyn for years, closed up shop forever.

This was serious stuff, and in 1911, the Brooklyn District Attorney, the State Banking Department, and other officials wanted to know how this happened. All of the investigations soon began to point to David A. Sullivan. When he was president, it appears that there was an insider bank officer clique, an inner circle that made dubious loans to dummy corporations and fraudulent loans to those who were clearly unable to repay them, while pocketing lucrative loan bonuses for themselves. When the loans inevitably failed, the losses were credited to the bank, and the game began anew. Each loan bonus represented 10 to 15% of the loan amount, and added up to hundreds of thousands of dollars. There were also serious allegations, once again, of cooking the books.

In August of 1911, David Sullivan was arrested for bank fraud. He was taken from his home at 179 Lenox Road, in Flatbush, and taken to the infamous Raymond Street Jail. Unable to make bail, he spent the night there, and was arraigned the next morning, charged with forgery in the third degree. Kenneth A. Southworth, cashier at the bank during the Sullivan tenure, was also indicted, and charged with forgery. During the court proceedings, the District Attorney, John F. Clarke, stated that Sullivan had “looted” the bank, and that he should be held without bail, as he was a wealthy man who could easily afford to leave town and disappear.

As Clarke was speaking, he and the judge both noticed that Sullivan had a huge grin on his face. The judge was not amused and ordered Sullivan to “stand up straight”, as he was leaning on the railing before the bench. Clarke went on to say, “Smiling as he is now, he told those who examined him that all he had was a silver watch and a shoelace. Everything is in his wife’s name, and there isn’t a dollar’s worth of property to keep him within jurisdiction should he remain away from trial. He has a splendid home, he rides around in an automobile, and is living in luxury, but he hasn’t a cent.” Clarke concluded by saying that Sullivan’s wife had the money, and bail should be set at $25,000, because he could get it if he had to. The defense attorney countered that Sullivan wasn’t a wealthy man at all, and Mrs. Sullivan only owned the house in Flatbush and one in the country, which she was willing to put up for collateral for bail. The judge set bail at $15,000.

As Sullivan and his attorney attempted to raise the bail money, time ran out, and Sullivan had to go back to the Raymond Street Jail. He asked that he be taken in a car with two detectives, instead of having to endure the embarrassment of riding in the common prison wagon. He rode in the prison wagon.

The other defendant, Kenneth Southworth, was ready to turn state’s evidence. He had already testified to a Grand Jury that at Sullivan’s direct order, he had forged entries in the Mechanic’s books to cover up a $100,000 bad loan, the day before the State Banking Department had come to examine the books, back in 1907. One of the bank’s account holders, a Mrs. Cheseborough, had $182,000 in her account. Southworth was instructed to withdraw $100K of her money, to cover up the bad loan.

This testimony was actually given to the Grand Jury empaneled in 1908, the one that suddenly stopped. Investigations into this event found that the day after the GJ ended, all of the records of the testimony disappeared without a trace. This also included the allegedly cooked books. It took investigators years to re-assemble their case. Southworth was crying like a baby, and told all. He said that he was “the tool of Sullivan,” and was one of the men in the infamous midnight party at the bank, when Sullivan had him change the Cheseborough ledger. As the investigations continued, evidence of phony checks made out to people Sullivan knew appeared, as did payouts to bogus loans. Old associates of Sullivan whose names appear on loans and accounts professed to know nothing about those accounts, and received no money, and did not take out any loans.

There was a whole lot of “I don’t know or remember” going on by business associates of Sullivan. One Robert P. Orr, a lawyer, and president of the Orr Contracting Company, a subsidiary of Mechanics and Traders Bank, testified that he knew nothing about what his company was doing. It had started with $500 in the bank, but two years later, had close to $1.5 million. Orr testified he had no idea, as he had only lent his name to some kind of company at the urging of his friend, Mr. Sullivan, and a cashier of the bank, Major Ashley. (Incidentally, cashiers were akin to bank officers today, and were not, as the name suggests, mere bank tellers.) Orr testified that his company would form a necessary link as a middleman for lending and receiving monies for Mechanics. The Orr Contracting Company was listed as the purchaser of several small banks, including Brooklyn’s own People’s Bank, and Pacific Bank, for which checks were issued for the total sum of over $810,000. When asked if his dummy company was a necessary thing, Orr replied that he was told by Major Ashley that it was, and was also perfectly legal. Orr claimed to have never made a cent on any of the deals. He knew nothing, he said, about any illegal or shady dealings.

On January 6, 1913, David A. Sullivan’s trial for larceny began in Supreme Court, Brooklyn; Justice Crane presiding. There were five indictments made against Sullivan which grew out of the 1911 investigation and Grand Jury. A special panel of 150 potential jurors had been drawn. Sullivan had requested that his trial be moved out of Kings County, as public opinion was not in his favor. Like his ride in the common jail wagon, three years before, his trial went on as planned.

Next: The conclusion. The trial. The verdict. The aftermath.

What's Your Take? Leave a Comment