How to Leave Brooklyn: A Farewell From Two Photographers

Photographers Alex Webb and Rebecca Norris Webb collaborate on a book paying homage to the borough.

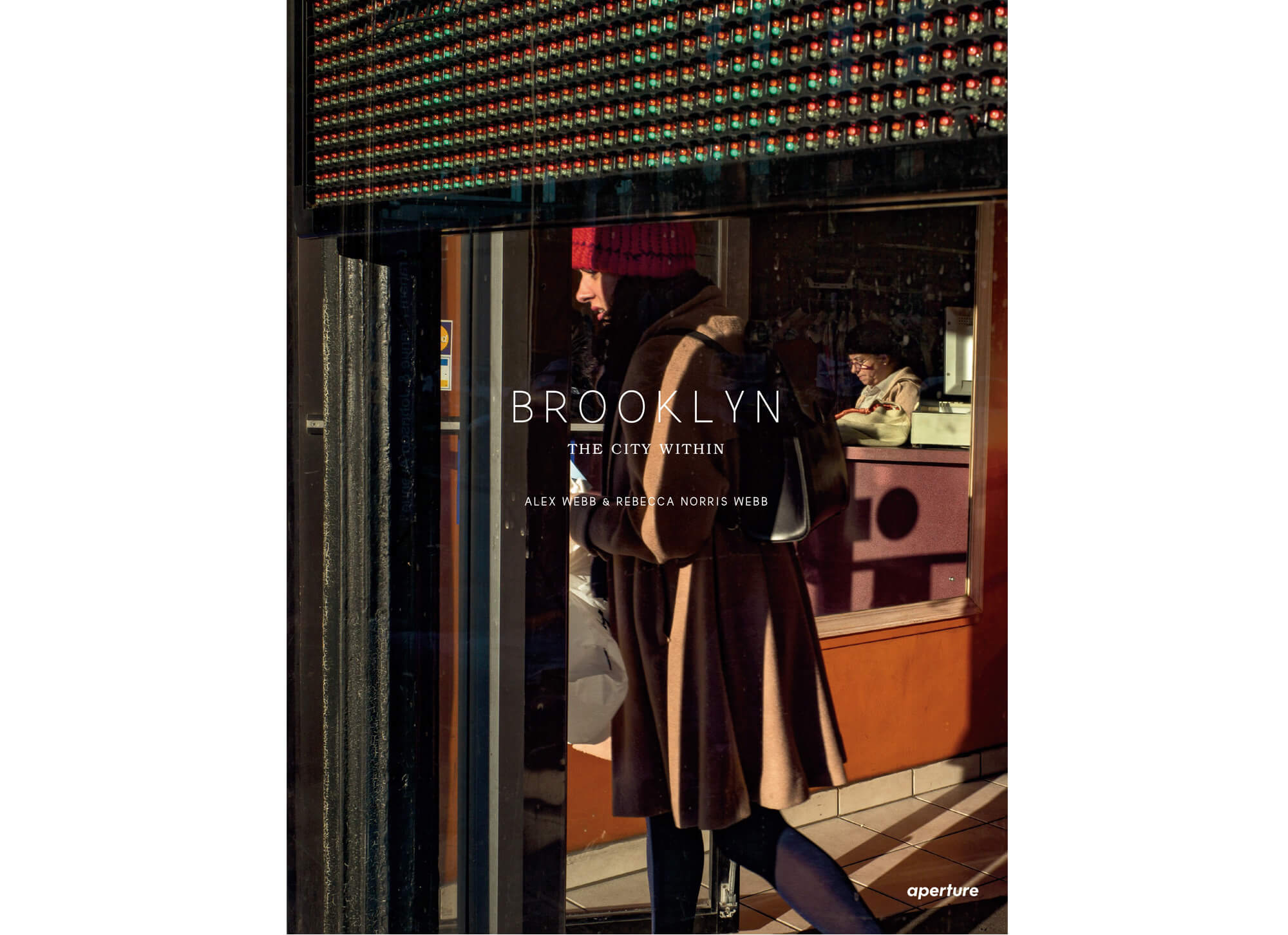

Alex Webb, Williamsburg, 2014

Photographers Alex Webb and Rebecca Norris Webb are leaving Brooklyn. Or at least they are planning on leaving sometime in the future. No firm plans have been set. They came to Park Slope around 20 years ago, after both having formerly lived in Manhattan and, at the time, there were practical reasons for the relocation. “We appreciate a more casual and neighborhood-oriented borough, not to mention a place where several of our friends—photographers, writers, and others involved in the arts—live nearby,” says Alex. It was the first place the couple lived together prior to getting married in 1999.

Looking into the future, though, they are open to change. “A few years ago, we realized much as we love Brooklyn, we’d like to spend the next chapter of our lives in a place where the natural world dominates,” Alex says, admitting that the choice has been complicated. Memories remain. Rebecca, whose photos tend to focus on landscape and the natural world, says she took some of her first important photographs at the Coney Island Aquarium in 1998, eventually leading to her first book, “The Glass Between Us.” (Alex, on the other hand, a street photographer and member of the Magnum photo agency, embraces shifting colors and light, often in foreign locations.) “So, for me, it’s been particularly hard to say farewell to Brooklyn, this place I’ve long considered my creative home,” Rebecca says.

When the idea came up to leave, they started thinking about a collaborative project that would serve as the beginning of a farewell, a way to “deal with this impending departure—and the unsettling emotions that accompany it,” Alex says. The result is “Brooklyn: The City Within,” a photo book published by Aperture in September.

Split into three sections, the middle of the book focuses on Rebecca’s photographs, mostly of Prospect Park, the Botanic Garden and Green-Wood Cemetery, “because the green heart where Rebecca has photographed lies in the center of the borough,” they write in the introduction to the book. It’s also where her interest in the poetic possibilities of the natural world take shape: a smudged shot of people trudging through Prospect Park during a snowstorm; the glowing eyes of an animal—a cat possibly, or maybe an owl—perched high in a thicket of tree branches; a man and a woman tightly embracing in the grass; crowds meandering through the bright red and purple flowers of the Botanic Garden on a summer day. In between these photographs, which, even when people are present convey a solitariness, are texts written by Rebecca. As in many of their recent collaborative projects, these writings illuminate her more abstract work. “Head bowed against this icy wind,” she writes about a particularly harsh winter, “I wonder how many of us now—this moment in Brooklyn—find ourselves inhabiting two worlds at once?”

This other world, perhaps, is what Alex documents in two different sections that bookend the project. He is drawn to the multitude of people who inhabit Brooklyn’s streets, from adults hurriedly exiting the subway to their office jobs in Downtown Brooklyn to kids playing outside their homes in Prospect Lefferts Gardens or climbing a fence in Bath Beach. Dense with information, his images are crowded and chaotic, demanding time to pull apart their layers. The writer Geoff Dyer has called Alex’s photos “complicated pictures of complicated situations,” which accurately describes both their formal properties and the content within the frame. He is drawn to large gatherings—in the book, we get pictures from the Mermaid Parade in Coney Island, Assumption Day in Bushwick, J’ouvert in Crown Heights, and the Ragamuffin Parade in Bay Ridge—as well as the way color, sunlight, and reflection can alter what would otherwise be a pedestrian image. The book brings to life the communities around us, those we both see and don’t see, and creates a portrait of home.

The idea of home has taken on different configurations in Rebecca’s and Alex’s work. Born in Rushville, Ind., in 1956, Rebecca is originally a poet, and where she is from and her original vocation greatly influence her photographic work. Aside from the projects she has worked on with Alex—”Violet Isle: A Duet of Photographs From Cuba,” “Memory City,” “Slant Rhymes,” and “Alex Webb and Rebecca Norris Webb on Street Photography and the Poetic Image,” a distillation of the workshops they teach around the world—her most startling book is “My Dakota,” which was published in 2012. What was initially a book about the Black Hills of South Dakota—where she moved at the age of 15 with her family—turned into something more ruminative following the sudden death of her brother. The book, which weaves poetry and images, became a meditation of the idea of home and the way grief and sadness can embed themselves in the landscape of a place. More recently, she has been working on a project called Night Calls, for which she retraces the route of her 99-year-old father’s house calls through Rush County, Ind., documenting the process along the way.

Alex, in some ways, has explored the idea of home elsewhere. Born in San Francisco in 1952, and raised in New England, he attended Harvard University, where he majored in history and literature and studied photography at the Carpenter Center for the Visual Arts. Steeped in the black-and-white photojournalism of the period, he began working as a professional photographer in 1974, moving to New York City two years later. Much of his early work explored parts of the Deep South and life along the U.S.-Mexico border, but it was the images that he started producing in the late 1970s, mostly working in the Caribbean and Mexico, that precipitated a shift to shooting in color, for which he is best known. His first book, “Hot Light/Half-Made Worlds: Photographs From the Tropics,” was published in 1986, marking him as one of the most distinctive photographers of his generation. More projects, expansions on the trips he was regularly making to the Caribbean, Latin America, and Africa, resulted in the books “Under a Grudging Sun: Photographs from Haiti Libéré,” “From the Sunshine State: Photographs of Florida, Amazon: From the Floodplains to the Clouds” and “La Calle,” a collection of his photographs from Mexico, among others. Alex is currently at work on a project documenting various American cities, such as Houston, Buffalo, Pittsburgh, and Chicago.

“When we first got together, we thought the idea of collaboration would be anathema,” Alex said at a recent presentation of the book in Manhattan. “We thought it would be the end of the relationship. Obviously, that changed.” What helped was that, among all their travels and the thousands of rolls of film that passed through their analog cameras, there was always a place to return to. In a piece included in the book, Rebecca writes of flying over Brooklyn at night on their way back from a trip. “Adrift in all that luminance, Prospect Park passes beneath us like a great dark ship, built of ironwood, hornbeam, scarlet oak,” she writes. “In its wooden hold, I know that we are home.”

Your methods of how you approach taking pictures in Brooklyn seem to differ. Can you talk about those different approaches and how that is reflected in the book?

AW: Ever since my early trips to Haiti and the U.S.-Mexico border nearly 45 years ago, I’ve often been drawn to cultures outside of my own, especially those from Latin American and the Caribbean. Photographing in these places—where intense light and vibrant color seem almost embedded in the culture—led to my switching from black and white to color. While working on “Brooklyn: The City Within,” although I photographed all over the borough, I repeatedly found myself attracted to some of the same Latin and Caribbean cultures that I’d photographed elsewhere. But instead of traveling by airplane, I simply took the subway.

RNW: Certain landscapes call to me, especially in places where I’ve lived or spent considerable time in, including most notably South Dakota, the sparsely populated state on the Great Plains where I came of age. That’s where I worked on my third book that interweaves my photographs and spare text, “My Dakota,” a kind of road trip of my grief for my brother who died unexpectedly. My response to the first death of an immediate family member was to drive restlessly through the badlands and prairies of South Dakota, the only place that gave me solace during the darkest time of my grief.

Walking and photographing Prospect Park, Brooklyn Botanic Garden, and Green-Wood Cemetery was not only about photographing the green spaces that I love near our Park Slope neighborhood. It also allowed me to return to my street photography roots, particularly the work of Bensonhurst-born Helen Levitt, a contemporary of Walker Evans, James Agee, and Henri Cartier-Bresson. When I first moved to New York from the Great Plains some 30 years ago to study at the International Center of Photography, I was inspired by the work of Levitt, one of the first women street photographers, especially her spontaneous photographs of children at play. No surprise that Levitt makes an appearance in one of my text pieces in the book, whose first line arose from walking along Long Meadow at dusk when the street lights were coming on.

Are you thinking of your pictures of Brooklyn as being in dialogue with those that came before?

AW: If one photographs a place, almost inevitably one becomes aware of the weight of past photographs. However, the images that I particularly remember of Brooklyn are largely in black and white, ranging from the work of Robert Frank, Bruce Davidson, and Garry Winogrand, to more recent images from Eugene Richards, Bruce Gilden, and Thomas Roma. As a color photographer now for some 40 years, photographing Brooklyn in color has seemed like unexplored territory.

RNW: Besides my work being in dialogue with Helen Levitt, Saul Leiter, and other lyrical New York City street photographers, it’s also in conversation with the rich literary tradition of Brooklyn, notably Marianne Moore, who lived in Fort Greene, where the younger poet, Elizabeth Bishop, would sometimes visit her mentor. Many of us Brooklynites are acquainted with the rather odd-looking tree near the boathouse in Prospect Park, which looks like an oversized bonsai tree—the Camperdown elm. About 50 years ago, Moore wrote a poem to raise awareness and funds to save the struggling elm. Both the Camperdown elm and her poem— engraved on a plaque nearby—endure.

As longtime residents, did anything surprise you about Brooklyn while working on this project?

AW: Brooklyn is huge and varied, so there are large expanses of the borough that I— even as a longtime resident—still know little about. So for me, the process of photographing Brooklyn was exploratory and occasionally revelatory. One summer in Bushwick, I was delighted when a Mexican family invited me in for tamales during an Assumption Day festival. At a street fair in Park Slope, I was astonished to come upon a sea of bubbles. During J’ouvert—a festival that begins at 4 a.m. before the West Indian Day Parade during Labor Day weekend—the surreal scene of oil-covered revelers transported me back to Grenada’s Carnival, which I’d photographed many years before.

RNW: The day after learning that my friend, Diana Willensky Thompson, had died—the daughter of the former Brooklyn borough historian, Elliot Willensky—something extraordinary happened. While photographing in Green-Wood Cemetery hoping to ease my sadness, I noticed a small dove walking towards me. It paused in the threshold of the Garden Mausoleum to inspect a dead dragonfly. I leaned over to photograph the pair. Then something happened that has never happened in some 20 years of photographing animals around the world. Flying up, the bird lit on my finger. “Hello, Diana,” I said softly to her, which made me smile. I gently set the dove down on a stand of plastic flowers to honor the dead, and she lingered there for a good ten minutes as if sharing my reluctance to part ways.

Are there parts of Brooklyn you were never able to capture?

AW: Though I set out to photograph all over Brooklyn, I’ve never envisioned my work as any kind of complete portrait of the borough. I’ve photographed long enough to know that serendipity plays an immense role in my photography and that sometimes I simply don’t find photographs—or they don’t find me. I accept that my photography is 99.9 percent about failure.

RNW: I agree wholeheartedly. No one book can capture all the worlds that make up Brooklyn. At best, it’s just one more voice—or in our case, two voices—added to the chorus that is Brooklyn.

Editor’s note: A version of this story appeared in the Fall/Holiday 2019/20 issue of Brownstoner magazine.

Related Stories

- Actor, Activist and Designer Gbenga Akinnagbe Finds a Home in Bed Stuy on His Way to Broadway

- Photographer Rafael Rios Captures Fort Greene Relations in New Book

- Nostrand Avenue, A Train, Notorious B.I.G. Inspire Rising Photographer Deana Lawson

Email tips@brownstoner.com with further comments, questions or tips. Follow Brownstoner on Twitter and Instagram, and like us on Facebook.

What's Your Take? Leave a Comment