Walkabout: The Boss, the Wife, and the Rug Patrol, Part 2

Officers Grant, McKee, Donlin and Sullivan were part of a special unit – the Sanitary Squad. The year was 1901, and the place was Remsen Street in tony Brooklyn Heights. In June of that year, these officers were doing what they had been assigned to do for close to a year: they were looking for…

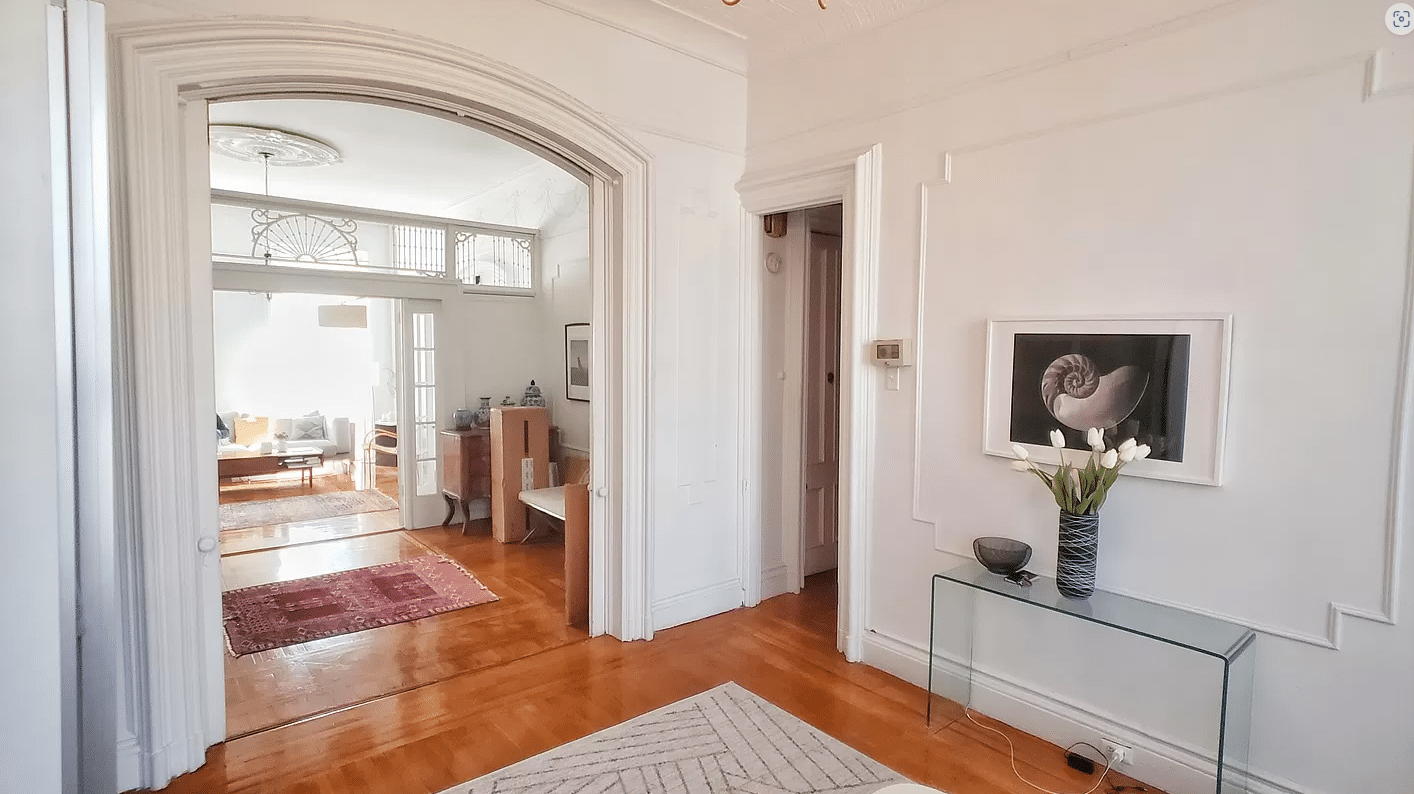

Everyone on this block of Remsen Street knew who the perpetrator was. Everyone, especially the neighbors on either side of 165 Remsen, had been the victims. This block was populated by some of the wealthiest and most important people in the city. This was Remsen Street, one of the premiere blocks of Brooklyn Heights, home to doctors, politicians, financiers, lawyers, and well-paid professionals. 165 Remsen belonged to Dr. Frederick Wunderlich, a distinguished, well-known and highly regarded medical doctor. He had lived in this house for about six years when the trouble went down, with his wife, children and a staff of several servants.

Mrs. Leila Wunderlich was originally from New Orleans. Perhaps that Southern Belle upbringing gave her a sense of entitlement and command, because by all accounts, she was not the easiest person to get along with, as her neighbors would attest. Dr. Wunderlich was loaded, and she enjoyed the finer things in their home, including a nice collection of Persian carpets and rugs. Leila was a fastidious housekeeper, and kept her staff busy, cleaning all day. Her husband could probably have operated on the floor, it was so clean. But rugs are a pain. They are beautiful, but you walk on them, and Brooklyn in the early 1900s was a dirty place, with cobblestone streets, the el trains spewing soot and dirt, horses and carriages, pollen, leaves, and all kinds of dust and dirt. The rugs and carpets needed frequent cleaning, and the Wunderlich family had an old German servant named George Meyerhoffer whose job it was to do just that.

The idea of Public Health in Brooklyn was catching on. The city realized that there were some health issues, like the spread of disease, that needed a rapid response by a city government that would be accountable and responsible for the public good. The city established all kinds of sanitary codes which prohibited certain activities within the city limits. Rug beating in yards and streets was one of those activities, for the obvious reason that in a tight urban situation, the dirt and dust generated from beating rugs outside could spread airborne germs and disease, and on top of that, was not very neighborly, as it deposited dirt and dust in right into people’s homes if their windows were open, and the wind was right. In addition, the noise from someone beating a rug was an intrusion, and if at the wrong hours, could keep someone from the quiet enjoyment of their homes, not to mention sleep. But Leila didn’t care. Laws were for other people. Her need for a spotless home trumped any silly law, or the quiet enjoyment of her immediate neighbors.

One of those people was her next door neighbor, Hugh McLaughlin, the infamous Democratic Party Boss of Brooklyn. McLaughlin had worked hard to get to his nice house on Remsen Street. He had come from dire poverty, and worked on the Brooklyn docks, catching the eye of the local Democratic Ward boss. In a number of years, he was running the docks, and then running Brooklyn’s Democratic Party, working hand in hand with Tammany Hall in Manhattan. Politics really hasn’t changed much, we’re just more subtle now, but back then, it was the politics of bare knuckle brawling, patronage jobs, intimidation, payoffs and power. Both sides did it, and the bosses of both parties were feared and powerful men.

Hugh McLaughlin had become a wealthy man, ostensibly through real estate, and had shocked the blue blooded Brooklyn Heights establishment when he purchased his house in the same neighborhood as the Pierreponts, Lows, Prentices and other silk-stockinged Old Brooklynites. But he proved to be a good neighbor on Remsen, wanting only to bring his daughter into Society, and live a life he probably never thought would have been possible as a lad selling fish on the docks. The worst thing about living there was not the snobby blue bloods; it was his neighbor, Mrs. Wunderlich, and her damn rugs.

She had been warned. Complaints had gone out, not only from the McLaughlin’s, but from Dr. Parker, the neighbor on the other side of the Wunderlich house, as well as from a Dr. O’Connell, the police department surgeon, and former Justice Frederick A. Ward, and newspaper man J. Cobb, all of whom lived on this block of Remsen. The health officers had come to the Wunderlich home, and told Leila that her servants could not beat the rugs in their backyard, it was a violation of the health code, and if they didn’t stop, she and her servants could be arrested and fined. For a while, it worked, a cleaning service came and picked up the rugs, and returned them, floor ready. But after a while, the cleaning service was no longer seen, and the rug beating began again.

The neighbors put up with it for almost a year, because Leila was very, very good at being crafty. She had the servants go on the roof of her extension and beat the rugs at five in the morning, or after midnight. The neighbors complained, but because of the hours, no authorities caught anyone in the act. During the spring and summer, no one could open their windows in the rear, because dirt and dust blew in regularly. People complained about lack of sleep, but Dr. Wunderlich made himself invisible, as far as the problem went, and Leila didn’t care about anything except her home. The health officers were assigned to the roofs to catch the servants in the act, which would allow them to make an arrest, but they never saw the rugs, or the servants, no matter when they were out there.

The newspaperman, J. Cobb, and the next door neighbor, Dr. Parker, couldn’t take it anymore. Both went to the Health office and offered whatever help they could. Mr. Cobb, as per his profession, kept odd hours, and promised to keep a look out. Dr. Parker, who lived at 167, promised that if the police came, he would keep his scuttle open, thus allowing the police access to the back yard, and from there, they could get to the Wunderlich roof. The trap was set.

Soon after, on a Saturday in June of 1901, Mr. Cobb ran into the Health Office, just as it was closing, and announced, “They are at it now, if you hurry, you can catch them.” Officers Grant and McKee ran to Remsen, entered through Dr. Parker’s place, and caught elderly George Meyerhoffer, the Wunderlich servant in charge of the rugs, holding the carpet switch in his hand, with a rug on a clothes line before him. Caught red-handed, as it were. He was arrested and kept overnight, and arraigned before a judge the next day. Mr. Meyerhoffer told the judge in broken English that it was his job to beat the rugs, but he didn’t own the house or the rugs, and was only doing what he was ordered to do. No one from the Wunderlich household came to be with him in court, or bail him out. The judge released him with Meyerhoffer’s promise to be in court at the appointed date.

Two weeks later, the case was up before the judge again, and George Meyerhoffer appeared, and was questioned through a German interpreter. This time, the Wunderlich’s sent their lawyer, George F. Eliot, to court; although they did not appear themselves, and he told the judge that the Wunderlich’s would stop beating their rugs, and would once again send them out to be cleaned. There was no reason to send poor old Meyerhoffer to prison, and it would never happen again. The judge and the Health Department agreed, saying that they only wanted the activity to stop, and were not interested in imprisoning old servants who were only following orders. Mr. Meyerhoffer was sent home.

You’d think that would be it, and the case of the rug beating servants would be over. Remsen Street would go back to normal and its residents once again able to open windows or sleep. You might think that, if you were Hugh McLaughlin, or Dr. Clark, but you would be wrong. By September, the slap of the carpet switch against a dirty rug could be heard again across Remsen Street. This time, it was even louder and more powerful. Someone was beating the carpets at 165 Remsen Street, and this time, McLaughlin and neighbors vowed, someone was going to pay.

It was too great a story, and gets even more complicated. Read about arrests, court, fines, parades, brass bands and bunting when this story concludes.

brooklyn has not changed one bit.

I think someone would have to beat me to get me to take out a rug and beat it. 🙂