Walkabout: Schubert’s Dyker Heights Symphony, Part 1

Read Part 2 and Part 3 of this story. As most people know by now, the city of Brooklyn developed from the six original towns settled by the Dutch, or in the case of Gravesend, the English, in the mid-1600s. Using their English names, they were Brooklyn, Bushwick, New Utrecht, Flatbush, Gravesend and Flatlands. England…

Read Part 2 and Part 3 of this story.

As most people know by now, the city of Brooklyn developed from the six original towns settled by the Dutch, or in the case of Gravesend, the English, in the mid-1600s. Using their English names, they were Brooklyn, Bushwick, New Utrecht, Flatbush, Gravesend and Flatlands.

England took over the whole thing soon afterward, calling the territory Kings County. Over the course of the next two hundred years, those towns grew to encompass smaller villages, adjacent cities like Williamsburg and Ridgewood, and stretched and moved around to become the boundaries of Brooklyn that we know today.

As the city grew, those separate towns, which once had space between them, grew closer and closer to each other, as farms and estates became streets and plots.

The city spread out in all directions out from the Brooklyn Heights shoreline, as roads and public transportation made it easier and easier for people in the outlying areas to be connected to Brooklyn’s piers, and on to jobs and markets in Manhattan.

The different neighborhoods grew organically, but by the turn of the 20th century, real estate developers with big dreams got into the job of neighborhood making. Unlike their compatriots who were building all kinds of row houses for the various urban neighborhoods, these men all wanted to create upscale suburbs for the growing number of people with means.

This demographic wanted the convenience of city life, but could afford the luxuries of the suburbs, with detached houses on large plots, landscaped streets and the assurance that they would be surrounded only by people just like them.

The suburban neighborhoods of Flatbush are the best known of these communities, started with Tennis Court, followed by Dean Alvord’s Prospect Park South, the communities of Ditmas Park, Beverley Square East and West, and so on.

The only other undeveloped part of Brooklyn at that point was the farmland and fields of New Utrecht and the other southernmost reaches of Brooklyn.

Several canny developers scoped out their territories there and began buying up land and building new suburbs, even before many areas of Flatbush. Those communities included Bensonhurst-By-the-Sea, Borough Park and Dyker Heights.

Dyker Heights was just hilly woodland in the 1820s when Brigadier General Rene Edward De Russy of the United States Army built his home on top of the highest point of the Heights, overlooking the harbor.

De Russy was a military engineer who built forts all across the new nation, including nearby Fort Hamilton. His home on the hill gave him a great view of Kings County’s defenses, including the new fort below him, which was completed in 1831.

In 1888, long after his death in 1865, De Russy’s widow Helen sold the estate to Frederick Henry Johnson and his wife, Jane Elizabeth Loverage.

Johnson already lived in New Utrecht, of which this land was a part, and was one of the town’s leading citizens. At that time, New Utrecht was still a separate and independent town, a part of Kings County, but not a part of the city of Brooklyn.

Johnson pushed hard within local and Brooklyn governments to have New Utrecht annexed to Brooklyn, a goal achieved in 1894. Of course, only four years later, the City of Brooklyn was itself made a part of the Greater City of New York.

Frederick Johnson was in real estate, and aside from buying a really choice piece of land overlooking the harbor as a home, he knew that New Utrecht was ripe for development, and that he was in the perfect position to do it.

He admired James D. Lynch’s Bensonhurst-by-the-Sea, which was touted in the Brooklyn Eagle and other newspapers and trade periodicals as the “most perfectly developed suburb ever laid out around New York.”

He wanted to make his new land purchase the same kind of community. But before he could really put his plans to fruition, Frederick Johnson died at the age of 52, in 1893.

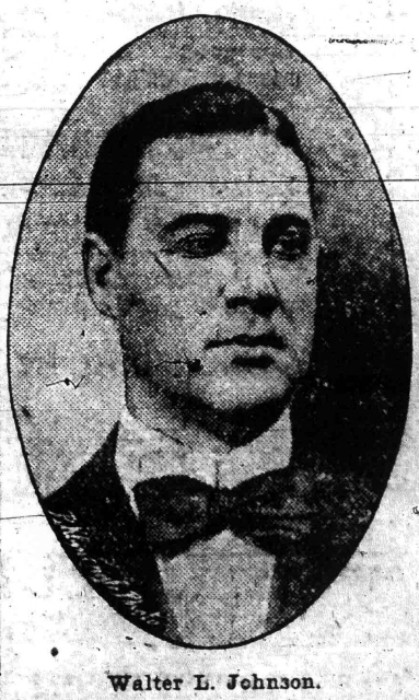

Walter Loverage Johnson was the second son.

At the time of his father’s death, he was employed as the private secretary to the Fire Commissioner of Brooklyn, W. C. Bryant. As the trusted aide to an important city official, Walter Johnson knew everyone in Brooklyn city government; all of the various commissioners, their aides, and all of the functionaries whose good will could make any of his building endeavors a lot easier.

Walter had inherited his father’s dream to create a new suburban neighborhood in New Utrecht, but it would take time to set it all up.

He set up the infrastructure part of his development, but remained with the Fire Commissioner’s office until 1897. At that time, the Brooklyn Eagle ran a short paragraph noting that Johnson had tendered his resignation with the intention of going into real estate development full time.

Johnson named his new community Dyker Heights, as his family land over looked Dyker Meadow and Beach. He would begin by parceling off his own family land, build houses, and take it from there.

His land was mostly woods, and the surrounding area didn’t have much in the way of roads, so Johnson’s first job was to extend the street grid across his property, cut down the trees and grade the properties, pave those streets, and then lay water, utilities and sewer lines across the plots.

He then paved the sidewalks, landscaped the area with sugar maples. All of this work gave him over 200 plots of land to develop into housing.

His connections to the infrastructure of the city served him well, as he was able to get together with several influential members of the greater civic/architectural/financial community, and get them excited about Dyker Heights. He started small, building only three houses.

One of his first converts was Walter Parfitt, the eldest of the Parfitt Brothers, one of Brooklyn’s most prestigious architectural firms.

Parfitt designed all three houses, which included one for Johnson, one for Arthur S. Tuttle, the Assistant Engineer of The Water Supply of The City Works Department of The City of Brooklyn, certainly a good guy to have on your side, and one for himself.

The houses were large, sprawling suburban manses, which were greatly admired. Johnson named his house “Hill Crest.” They kicked off the first round of Dyker Heights homes, thirty in number, which sold as soon as they were finished.

And why not? He was building in one of the most beautiful areas of Brooklyn, on high ground, with seaside vistas, cooling fresh breezes, and lots of room.

He also had established a series of restrictions and ground rules which guaranteed that the community would remain economically exclusive, the houses would conform to standards of quality, and the population would be of the proper class and refinement.

Walter Parfitt designed other houses in the neighborhood, but he was not interested in being a co-developer. He had a large family, and was getting on in age, and wanted to live in semi-retirement, enjoying his children and grandchildren.

Johnson employed other architects, including John J. Petit, would soon be employed as the chief architect of Dean Alvord’s Prospect Park South neighborhood. He designed a beautiful Tudor style house for the Siatta family on land they purchased in Dyker Heights from Walter Johnson.

That house is one of the very few landmarked properties in this neighborhood. Walter Johnson needed an architect who could design for the long haul. He found him in the person of Constantine Schubert.

Constantine Schubert, who rarely used his first name, and appears on 99% of documentation about him as “C. Schubert,” was born in 1859. His parents were both born in France, and immigrated to the United States in the mid-19th century, before his birth.

He was born in Manhattan. I do not know if he was related to the great Austrian composer Franz Schubert, who died in 1828. Young Constantine was a natural and gifted artist.

His drawings won awards throughout his early days, even before he became an architect. He got his architectural education from Cooper Union, where in 1877; he was first in his class in mechanical drawing.

He first starts to show up in the architectural records in 1882, and sets up his offices in Bay Ridge. A smart move, as the very southern parts of Brooklyn was on the verge of taking off, and he was in a position to design buildings not only there, but anywhere else in Brooklyn.

Over the next two decades, he is on record with buildings in Bath Beach, Coney Island, Bay Ridge, Gravesend and Borough Park. Where architects like Montrose Morris, George Chappell and Theobald Engelhardt specialized in building mostly in their own neighborhoods of Bedford, the St. Marks District and the Eastern District, respectively, Schubert found his niche in southern Brooklyn.

He began designing suburban houses for Walter Johnson. Their relationship would last for a long time, and through different names and companies. Together, they built Dyker Heights. We’ll get into that next time.

What's Your Take? Leave a Comment