Walkabout: Schubert’s Dyker Heights Symphony, Part 3

Read Part 1 and Part 2 of this story. Developer Walter L. Johnson was a powerhouse. When he began building his Dyker Heights suburban community, he went with the best of the best. First of all, he had one of the best locations in Brooklyn to work with. His father had purchased the old DeRussy…

Read Part 1 and Part 2 of this story.

Developer Walter L. Johnson was a powerhouse. When he began building his Dyker Heights suburban community, he went with the best of the best. First of all, he had one of the best locations in Brooklyn to work with. His father had purchased the old DeRussy estate back in 1888 with the idea to develop it into an upscale suburban community.

The estate was on high ground, with magnificent views of the New York harbor. You could see from the Narrows all the way out to Sandy Hook and beyond. The air was clean and cooling, and living here would be the best of both worlds; a seaside house with easy access to the big city.

Johnson’s father, Frederick, did not get the opportunity to carry out his plans, as he died in 1893, but he passed his vision on to his second son, Walter.

As soon as the opportune moment arrived, Walter began building; first limiting himself to three houses, one for himself, and when great interest was garnered, began with thirty similar houses to kick off his new community that he called Dyker Heights. His first architect was one of his first clients; the eminent elder partner in the Parfitt Brothers firm, Walter Parfitt.

Parts One and Two of this story lay out their first venture. Dyker Heights became home to a very elite group of homeowners. They were mostly upper class Episcopalians.

The first church in Dyker Heights was St. Phillip’s Episcopal Church. The community was marketed towards the Wall St. crowd, and they came, but interestingly, there were also a sizable number of current or former city officials along with the bankers, brokers and industrialists.

Before Walter Johnson had gone into full time development, he had been with the city as the private secretary to Brooklyn’s Fire Commissioner. He was there for many years, and had nurtured relationships with the heads and junior heads of many of the city’s agencies.

By the time Dyker Heights was a reality, many of the heads had retired, and more than one of the juniors was now in a senior position. Some of those men came to live in Dyker Heights.

Wealthy and connected early residents included I. M. De Varona – Engineer of the Water Bureau, Clarence Barrow – the Ex-Fire Commissioner, William C. Bryant – the current Fire Commissioner, George W. Dickinson – cotton-goods merchant, W. Bennett Wardell – retired Judge, Richard Perry Chittenden – Assistant of the Corporation Counsel, Freeland Willcox – Secretary of the Cheeseborough Vaseline Company, and Eugene Boucher, a longshoreman and insurance broker.

In order to insure architectural continuity, as well as to abide by the restrictions Johnson wrote into the community charter, he hired a full time architect to bring his vision to life. Walter Parfitt designed the first thirty houses, but local architect Constantine Schubert designed the rest.

The original Dyker Heights community had about 150 houses. Schubert not only designed the homes, he lived in one, and was president of the 30th Ward Improvement League. Their function was very much like that of a modern-day community board.

He and Johnson, along with Walter Parfitt and others, were a formidable force. They pressured the city for services; they encouraged home buying, and in general, made sure Dyker Heights remained the community they wanted it to be. That included keeping people out.

Ironically, today the majority of the homeowners of Dyker Heights are Italian American. Back in Johnson’s day, he did his best to keep most Italians out.

He made an exception with the Simone Siatta family, a wealthy Manhattan fruit wholesaler, and the family of Dr. Lorenzo Ullo, who was Counselor to the General Company of Italian Navigation. But other Italians, especially those of lesser means? He wasn’t having it.

The Brooklyn Eagle reported in 1897 that one of Johnson’s homes was being rented by an Italian family. When he found out about it, Johnson went over there and paid them $600 to move. He told the paper that his community was very carefully restricted, and it wouldn’t do to have any objectionable features about it.

Nice guy. Dyker Heights’ restrictive covenant expired in 1915, opening up the community to all kinds of people, as well as an end to the kind of architecture that could be built there.

By that time Walter Johnson and Constantine Schubert had moved on to new developments. Dyker Heights was basically finished by 1905. While he had been working on the community, Johnson had also kept his eye out for more land in the general area.

In 1898, he got his hands on a big chunk of it. The Bay Ridge Park Improvement Company was in financial trouble. Johnson was able to buy 350 lots from them, which included land along 83rd, 84th, 85th, and 86th Streets through 12th, 13th and 14th Avenues. He paid $425 a lot, the sale totally about $150,000. He planned to build detached single family houses there.

In 1900, in the middle of the night in March, the Johnson family home in Dyker Heights burned down. The family and three servants ran into the street in their night clothes, not able to salvage anything. Faulty wiring was judged to be the culprit. Walter and his family were able to stay nearby with his mother.

This was not the first time a Johnson home had burned down. When Walter was younger, and his father Frederick was still alive, their home, at the same location, had also burned to the ground. It was thought to be accidental, but it was always deemed more likely that Frederick had burned it down for the insurance money. That was not the case this time.

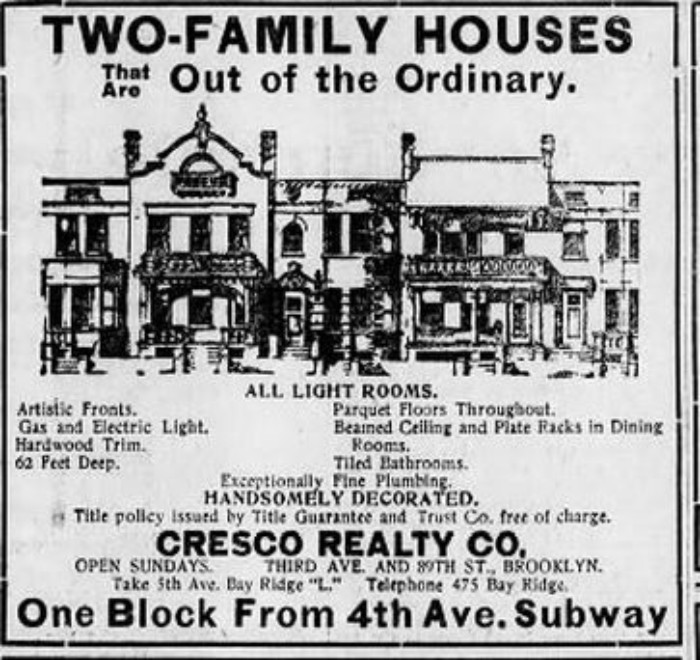

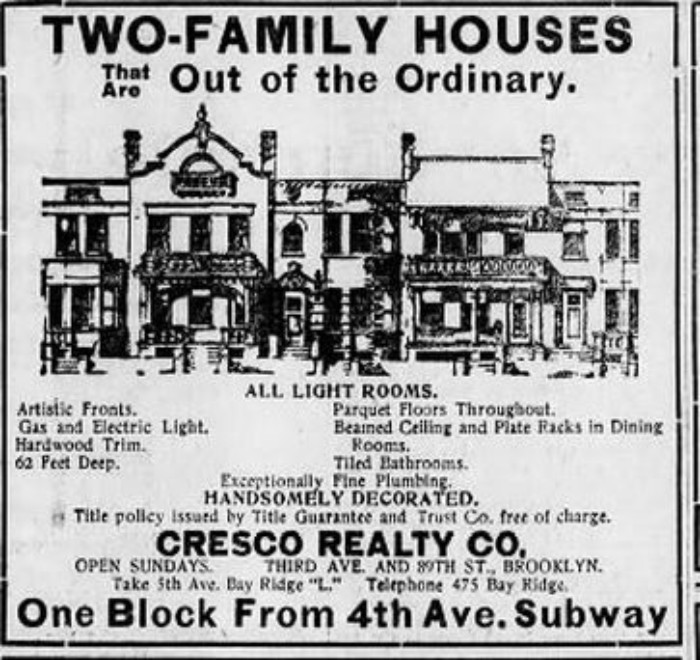

By 1906, Walter Johnson had established a new development company. It was called the Cresco Realty Company. Their sole neighborhood seems to be Bay Ridge, developing the plots that Johnson had purchased from the Bay Ridge Park Improvement Company.

By that time, as announced in the New York Times, Johnson had bought up the entire inventory of that company, totaling over 600 plots, for an expenditure of $350,000. This included land from 68th to 86th Streets, 10th to 14th Avenue.

I don’t know if he was able to develop it all, but he and Schubert certainly built on some of it. Bay Ridge was not Dyker Heights; it was a much more middle class neighborhood, where row houses would be the best investment strategy for the lots involved.

By 1907, row house design had changed from the familiar brownstone and limestone row house block of brownstone Brooklyn. People wanted new designs. They also didn’t want, and couldn’t afford large single family houses. So Schubert and Johnson gave them something new – two family row houses in a multitude of style.

Some of their Bay Ridge blocks are quite interesting, with a mélange of styles that often doesn’t look like it has a rhyme or reason. Of course, upon closer look, there is one. They were all two story houses, with an apartment above and below.

Many had upper story front porches and decks. The styles reflect a pastiche of what was going on in other neighborhoods. If you wanted a limestone, they had one. If you wanted a brick house with an overhanging porch, that was next door.

Check out the photographs below. Johnson and Schubert had quite a modern, 20th century symphony of style here. Some might say more Stravinsky than Mahler – but for Brooklyn, at that time, quite modern indeed. Johnson and Schubert should be added to the pantheon of developers and architects who truly shaped Brooklyn.

(Brooklyn Eagle Ad, 1907)

GMAP

What's Your Take? Leave a Comment