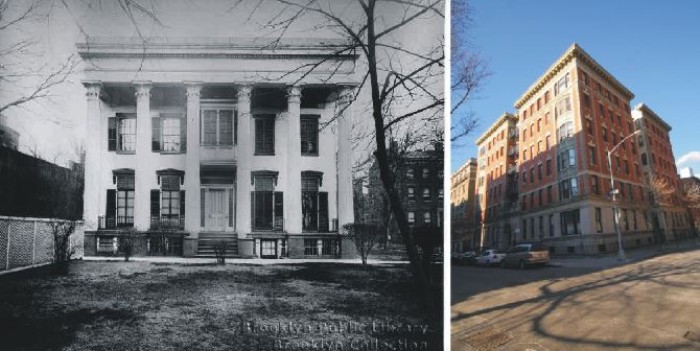

Past and Present: The Henry C. Bowen Mansion

There was a time in Brooklyn’s history when Mr. Henry C. Bowen was one of Brooklyn’s favorite sons. He was a wealthy man, owner of two newspapers, and his home on the corner of Willow and Clark Streets was described as the Heights’ most beautiful home. Henry C. Bowen was a very devout and religious…

There was a time in Brooklyn’s history when Mr. Henry C. Bowen was one of Brooklyn’s favorite sons. He was a wealthy man, owner of two newspapers, and his home on the corner of Willow and Clark Streets was described as the Heights’ most beautiful home. Henry C. Bowen was a very devout and religious man, whose strong moral beliefs led him to be involved in the founding of two churches, and made him one of the leaders in Brooklyn’s anti-slavery movement. Those strong moral beliefs also would lead to him being one of the most hated men in the city, vilified on the streets, in the pulpit and in newspapers across the country. When he died in 1896, all of that was forgotten, and he is now fondly remembered once again as one of Brooklyn’s leading men. He had an amazing life, and this house was at the center of it all.

Henry Bowen was born in Woodstock, Ct. on Sept. 11, 1813. He came from an old established New England family whose roots were watered by faith and commerce. Like many New Englanders, he came to New York and became a successful merchant. His first job, at the age of 20, was with the dry goods house of Arthur Tappan & Co. Five years later, he established his own company, Bowen & McNamee, later reorganized as Bowen Holmes & Co. They were purveyors of dry goods, silks and ribbons. His time with Arthur Tappan was well spent; he learned the trade, and married the boss’ daughter. His first wife was Lucy Tappan, and they would have ten children.

Many former New Englanders also settled in Brooklyn Heights, already a desirable suburb away from the hustle and bustle of Manhattan’s commercial sector. They built or moved into large homes on the hill overlooking the river, villas and city homes with large lots and gracious surroundings. The homes were on the site of former farms and orchards. They also established churches. Henry Bowen was one of the founders of the Church of the Pilgrims, a Congregationalist church founded in 1844. They hired Richard Upjohn to design what is now regarded as the first Romanesque Revival church in the country. It stands on the corner of Remsen and Henry Streets. Their first and most famous pastor was the Rev. Richard S. Storrs, Jr. who came to them from Massachusetts.

Rev. Storrs was a quiet man, but a great preacher. The church grew in size and importance, and was one of the early homes of Brooklyn’s abolitionist movement. Henry Bowen’s father-in-law, Arthur Tappan, was one of the most ardent and generous abolitionists in Brooklyn, and Bowen and his family were among the leaders and most enthusiastic workers for the cause. Two years after the founding of Church of the Pilgrims, a group of nine men, including Henry Bowen, was given permission to establish a new Congregational church in the Heights. This church would be called Plymouth Church, and its newly chosen minister was a firebrand preacher named Henry Ward Beecher.

Beecher was one of the greatest abolitionist preachers of his day. Plymouth became the center of white anti-slavery activity in Brooklyn, led by a man whose gift of oratory could bring angels down from heaven to weep at his feet. Thousands of people would travel to Brooklyn to hear him, and Plymouth Church was filled to the rafters every Sunday. Those dedicated to the cause must have been sure that slavery would end because Beecher would shame slaveholders into ending it. It wasn’t that easy.

Henry Bowen, who still had his successful dry goods business, went into the publishing business. He and four other merchants established an anti-slavery newspaper called the Independent in 1848. Bowen was the publisher and editor. The paper featured articles by some of the most important abolitionists in Brooklyn, including Henry Ward Beecher and Richard Storrs. There were also articles about Christianity in general, and the conundrum of living a godly life in a busy, hectic and ungodly world. It was a very thoughtful and intelligent magazine, and was soon very powerful and successful. Its editors never shied away from controversial topics and spoke their minds.

From all reports, Henry Bowen and his family lived in at least two different houses in the Heights. He is the owner of record of a Gothic Revival townhouse at 131 Hicks Street, built in 1848. According to the Brooklyn Eagle, he also lived at 76 Willow Street, before moving to this house, at 90 Willow Street, a house described as a “Colonial mansion” in all of the descriptions I found when the house was still standing, and afterward. Some reports, written long after the house was gone, place it between 1812 and 1820. Bowen did not build the house, as later accounts would reveal, he moved into it in the late 1840s or early 1850s.

There was no doubt, in anyone’s mind, whenever it was built, that this was one of the finest homes in Brooklyn Heights. One of Henry Bowen’s sons described the house in detail to an Eagle reporter, after the house was torn down. The house was a large Greek Revival temple front house, set back from the street on a large lot that once opened up on Columbia Terrace. There was a stable in the back. He said that it had a double parlor, with large pocket doors between that were often opened up for entertaining. The parlors had rich rose colored brocade draperies and jewel-toned rugs. The doors were fine mahogany with silver hardware.

The ceilings in the parlor were very special. They were both adorned with frescoes with cherubim popping out all over. The faces of the cherubs were all likenesses of the Bowen’s twelve grandchildren. There were also large religious paintings on the walls. The Bowen’s entertained often, and the house was almost visited by Abraham Lincoln. He had been invited to Plymouth Church while he was running for president, and was invited to the Bowen’s for lunch. He declined, as he had to work on his speech for that evening. That speech, given at Cooper Union on February 20, 1860, helped win him the presidency.

Henry Bowen would not compromise in his anti-slavery activities. In 1850, after the passing of the Fugitive Slave Act, which made it legal for slaveholders to come up north and recapture fugitives, Bowen, through the Independent went on the attack. It cost him business. Many Southern merchants would not buy his goods. He didn’t care, saying that “we have our goods for sale, not our principles.”

His stand made him more popular in the North and the business thrived until it finally went under as the Civil War began. Bowen was already quite wealthy, and turned his attentions to the Independent and his new insurance company, Continental Insurance, founded in 1853. He also immersed his time into his church, his anti-slavery activity, and his summer home, the now-famous Carpenter Gothic cottage in Connecticut called Roseland. The Independent and Continental Insurance would support his family for several generations to come.

In 1862, President Lincoln appointed Bowen to the position of Collector of Internal Revenue for the Third District of New York. He would hold that position until kicked out by Andrew Johnson, Lincoln’s successor. Johnson didn’t like Bowen’s opposition to his policies which he opined on in the Independent. In 1863, his beloved wife Lucy died here at home. Two years later, he remarried, and his second wife, Ellen Holt bore him a son, making them a family of eleven children, of which eight survived to continue the family.

After the Civil War, Bowen had full control of the Independent. The other co-owners sold out to him, making it his paper. Over the years he had had Beecher, Storrs and others edit the paper, but now it was his. In 1870, a huge scandal erupted, probably the greatest scandal of the 19th century. Rev. Henry Ward Beecher was accused of having an affair with Elizabeth Tilton, wife of one of the church’s leaders, Theodore Tilton, who had also been one of the editors at the Independent. The whole mess was covered up for years, but erupted in 1875, when Tilton sued Beecher, resulting in one of the great civil trials of that or any other century.

Beecher was one of the most well-loved and important figures in America, especially in Brooklyn. Accusing him of adultery in the strict Victorian society of the day was huge. It was also deliciously shocking and salacious. The trial was standing room only, with tickets scalped on the courthouse steps. Henry Bowen was morally outraged and saddened at the fall of one of his idols, a man he had helped put in place. He was also very loyal to his friend Theodore Tilton, who had been excommunicated from Plymouth. He wrote some very anti-Beecher articles in the Independent, and suddenly found himself the most hated man in Brooklyn. I’ll have to tell that tale another time.

After it was all over, Bowen spend a lot of time at Roseland, in Ct. He gave a lot of money to his hometown, and had celebrations and festivals on his grounds. He is credited for reviving the celebration of the Fourth of July, which would lead to it becoming a national holiday. When he came back to Brooklyn, he continued with his businesses, and the Independent also thrived. Henry Bowen died in 1896, at home in his bed. His last words were the “Amens” he answered, as prayers were being said. Subsequent obituaries and eulogies never mentioned the Beecher scandal or the lawsuit and public condemnation that followed. He’s buried in his hometown of Woodstock, near his beloved Roseland.

Ellen Holt Bowen and some of the children remained in the large mansion, but there were rumors that the family wanted to sell it. Ellen died here in 1903. A huge sale cleaned out everything in the house that same year. In 1904, the house was sold to a developer who announced that he was going to tear it down to build a hotel. That didn’t happen, but a large apartment building was built on the site. As with many historic properties with long and important histories, the papers mourned its loss, and then eagerly described the progress that would bring, in this case, the new luxury apartment building.

Wish more of these single family places were around — like Clinton Hill…