Walkabout: Stretching Forth the Saving Hand, a True Story, Part Two

Read Part 1 of the story. Like the Biblical Saul on the road to Damascus, William Gibb had a Revelation. The actor from Halifax, Nova Scotia had seen the light, and decided to turn from the stage, where he wasn’t doing well, anyway, to the pulpit. The year was 1888, and Gibb was filled with…

Read Part 1 of the story.

Like the Biblical Saul on the road to Damascus, William Gibb had a Revelation. The actor from Halifax, Nova Scotia had seen the light, and decided to turn from the stage, where he wasn’t doing well, anyway, to the pulpit. The year was 1888, and Gibb was filled with the zeal of the Lord. He began preaching in Nova Scotia, going from church to church until he was finally sanctioned by a non-denominational Pentecostal church, and installed as pastor.

He baptized children and adults, and officiated at weddings. He was married himself, and he and his wife would have been a tiny footnote in the religious life of Halifax, except for the fact that Gibb was sure God had bigger and better things in store for him, and those things were not in Canada. God was calling Reverend Gibb to Brooklyn.

By 1893, the Gibb’s were in Greenpoint, Brooklyn. He was in charge of a small mission church run by the Methodist Church, which was located in a former tavern on Meeker Avenue. Every evening, Reverend Gibb stepped up to his small pulpit, and preached to the faithful and the unsaved, alike.

The former actor knew his stage and his audience, and he used his theatrical experience to great effect. His voice carried, he had a great passion to save, and men and women were coming up during the altar call at the end of his sermon, and devoting themselves to God. They were giving up liquor and sin, and God’s holy army was growing, thanks to the Reverend, one soul at a time.

For many who are called, this would have been enough, but there was more going on than anyone knew. As told in our first chapter, one night, after a revival meeting and supper, the Reverend Gibb walked out of the mission and never came back. So did one of his congregants, a married woman named Kate Frost.

He left his confused and grieving wife; she left an angry husband and two of her three children. No one could believe it, until they showed up a month later, in a small church in Halifax, Nova Scotia, discovered in the middle of a two week revival meeting, where Rev. Gibb was doing what he did best, saving souls.

They told people they were married, and that her 13 year old daughter was theirs, as well. The church running the revival had been thrilled at the results the couple were getting, as their mission was aimed at wayward and runaway girls in that city, and many had come to the revival meetings, and were moved by Rev. Gibb’s gifts of oratory, and Mrs. Gibb’s sweet and beautiful singing voice. But once the elders of the church were told of how the Gibb’s had left Brooklyn, they were out. Done. Shut down. Halifax was no longer a welcoming place.

Gibb denied being the adulterous wife abandoning cad from Brooklyn. He insisted that it was pure coincidence that a minister of the same name and description originally from Halifax but living in Brooklyn had ruined his own good name.

That this man should be in the company of a woman with a 13 year old daughter, just like his own dear wife and child, was also a horrible coincidence, and he would be willing to fight to regain his good name, if only given the chance. But he was not.

Back in Brooklyn, Alonzo Frost, Kate’s abandoned husband, was still angry. He was a driver for the Havermeyer Sugar Company, and he wanted justice, and he wanted his wife and her lover dragged back to Brooklyn to face charges. Most of all, he wanted his daughter back.

The real Mrs. Gibb was also livid. Her husband had left her high and dry, with no means of support. But nothing was done, and the story of the philandering preacher left the headlines, and the minds of the public, which had moved on to new scandals and new people of interest. Two years passed.

It was now 1895. In a tiny one paragraph story in the Brooklyn Eagle, in March, it was announced that a woman called Mrs. Eliza Gibb, whose minister husband had abandoned here two years earlier, was now homeless, and had appeared at the County Hospital and Almshouse in Flatbush.

She told the administrators there that her husband was “a religious huckster who had a gospel shop.” She went on to explain that “he had a slick tongue and talked religion to one of his regular listeners, a woman who had $600. One day the woman and her $600 disappeared, and my husband followed them. I’ve taken care of myself ever since, and now I’m sick.” They admitted her to the hospital.

That same year, in September, a Greenpoint man entered the Beacon Light Mission at 23 Fulton Street, down near the docks and the ferry. This was a poor neighborhood, and the mission was filled with the outcasts of society and those who had nothing.

They came to pray, and to be comforted by a man there named Mr. Thomas, who with his wife, had brought comfort to them, and, as the Brooklyn Eagle said, “Reached out the saving hand” to his fellow sinners. The Greenpoint man was B.G. Taylor, a man who had an excellent memory for faces and names. He immediately recognized both Mr. Thomas and his wife. As the call went out for prayer, Mr. Taylor stood, and asked for prayer of his own.

He was praying, he said, for a woman in Greenpoint who had been abandoned by her evangelist husband. He was also praying for a man, an honest working man, who had been abandoned by his wife, when she ran off with the evangelist. That evangelist was near, he said, closer to Greenpoint than anyone would have suspected. No one else at the meeting knew what he was talking about, and joined in the prayer, with much sympathy for the afflicted. But Taylor was watching Mr. Thomas’ face as he prayed. There was no reaction whatsoever.

Taylor came back, this time with an Eagle reporter, and they approached Mr. Thomas. The reporter called him Rev. Gibb, and Thomas denied being that man. When asked if the woman sitting on the platform with him was Mrs. Frost, Thomas told the reporter, “That woman is my wife.”

Thomas then denied that they had ever been to Brooklyn before coming to the Beacon Light Mission. The reporter wanted to know where they had been before, but Thomas refused to answer.

William Watson, the director of the Mission joined the conversation. He urged Mr. Thomas to answer the reporter’s questions in order to clear up any misunderstandings, but Thomas refused, saying that it was no one’s business where he lived, now or before, and once before he had been accused of being someone else, by someone who had accosted him on the street, and he was not going to tell anyone anything. It was all a huge case of mistaken identity, and he needed to be left alone to continue God’s work.

Well, the reporter was not going to let that alone, he wrote up a long story rehashing the entire story of Rev. Gibb, Mrs. Frost, and the sad tale of the betrayed wife and abandoned husband. He also told of the Halifax debacle, and updated the public to reveal that Alonzo Frost had divorced his wife, and remarried, and that Mrs. Eliza Gibb had left the hospital and almshouse, and was now a cook for a private family. William Watson immediately dismissed “Mr. Thomas,” and the couple disappeared again, for a time.

Another two years pass. Thirty years beforehand, in far off England, a missionary named William Booth and his wife Catherine, had started preaching to the poor, prostitutes, thieves and other undesirables in London’s slums. They preached in the streets, and gathered followers, and began soup kitchens and shelters, eventually becoming, as Booth described, “an army for God.” This organization would become the Salvation Army. News of this Army became known in America, and outposts of the Salvation Army were established in the United States.

The Booth’s sent their son, Ballington Booth, to New York in 1890, to oversee the Salvation Army in this country, but dissention in the ranks caused Ballington and his wife to leave the Army, and start a new organization called God’s Volunteers of America. The Volunteers were set up in a similar way to the Salvation Army, and also gave its workers military rankings. One could move up the ranks with service to others, and dedication and faith. This group would become the Volunteers of America.

But first, they were God’s Volunteers, and in 1897, Lieutenant William H. Thomas was one of them, in charge of the barracks at Long Island City. His commanding officer was a Colonel Lindsay, and the good Colonel was not happy with his subordinate.

It seems that Lt. Thomas had neglected to pay board for not only himself, but also his wife. The Colonel transferred the couple to New Jersey, and began an investigation as to Lt. Thomas’ background. What he found out shocked him. Thomas had lied about everything, and was really a man named William T. Gibbs, the notorious philandering preacher.

Lt. Thomas was brought back to New York, and summarily stripped of rank, and dismissed. He took it all rather well, and told the Colonel that there were other missions, other armies, and he had always made a living, and wouldn’t starve. He then got a job as a cook at a travelling circus temporarily in Long Island City, and when they left town, he went back to preaching, and was soon in charge of services at the Ellis Mission in Long Island City.

Unfortunately, when the Volunteers tossed William Thomas, as he now called himself, he found he couldn’t support the woman he called his wife. She left him, and was now eking out a meager livelihood sewing neckties in Manhattan.

The Rev. Gibb had moved into the Edwards Hotel, in Greenpoint, which was the topic of last week’s Walkabouts, and how I stumbled onto this story in the first place. In July of 1897, he had been living there for about a week, but had not been paying rent. According to the Eagle, he would have been a former guest of the hotel, except that he managed to sneak in past the eagle eye of the proprietor, Mr. Silas Edwards, and quietly went to bed. Mr. Edwards assured the reporter that that would not be happening again. The Reverend owed him three days rent.

Silas Edwards was not the only one he owed money to. After his time with the Volunteers as well as the circus was abruptly ended, he had gone to live with his wife, who had rooms with an old friend, a Mrs. Waldron. The landlady was sympathetic, and was won over by the persuasive and smooth talking ways of the Reverend Gibb, and let him stay there while he looked for work.

But as the days passed, he wasn’t looking for work, and wasn’t helping around the house, or doing anything, and Mrs. Waldron had had enough, and told him he had to leave. His erstwhile wife had had enough too, and didn’t want to see him anymore. When Gibb came by the house to see her, Mrs. Waldron planted herself in the door, and told him that his wife no longer loved him, and wanted him gone.

Gibbs was now telling everyone that the first Mrs. Gibb was never his legal wife; that he had met her when he was an actor, and they had agreed to live together. She was not available for comment, but it was known that she had a wry sense of the absurd, and now went by the name “Mrs. Church.” The second Mrs. Gibb had returned with her daughter, and the child, now 18 years old, was had been reunited with her father.

Gibb still preached at the Ellis Mission, far enough from the controversy of Greenpoint. Reporters were calling at the Edwards Hotel, but as Mr. Edwards explained, they would not be finding him there, if he had anything to do with it. Gibb had come there last week with another missionary named Gray, Edwards explained.

They told him they had nowhere to stay, and no money, but if he gave them a room, they would work for their keep. They told him they were first class painters, so Edwards traded them room for painting work. “I put them to work on a Myrtle Avenue store, and when I came around to see what they had accomplished, I quickly came to the conclusion that I would have been money ahead had I given them their room rent free. If Gibb can’t preach any better than he can paint, I’m not surprised he was dismissed by God’s Volunteers.” Can the church say “Amen?”

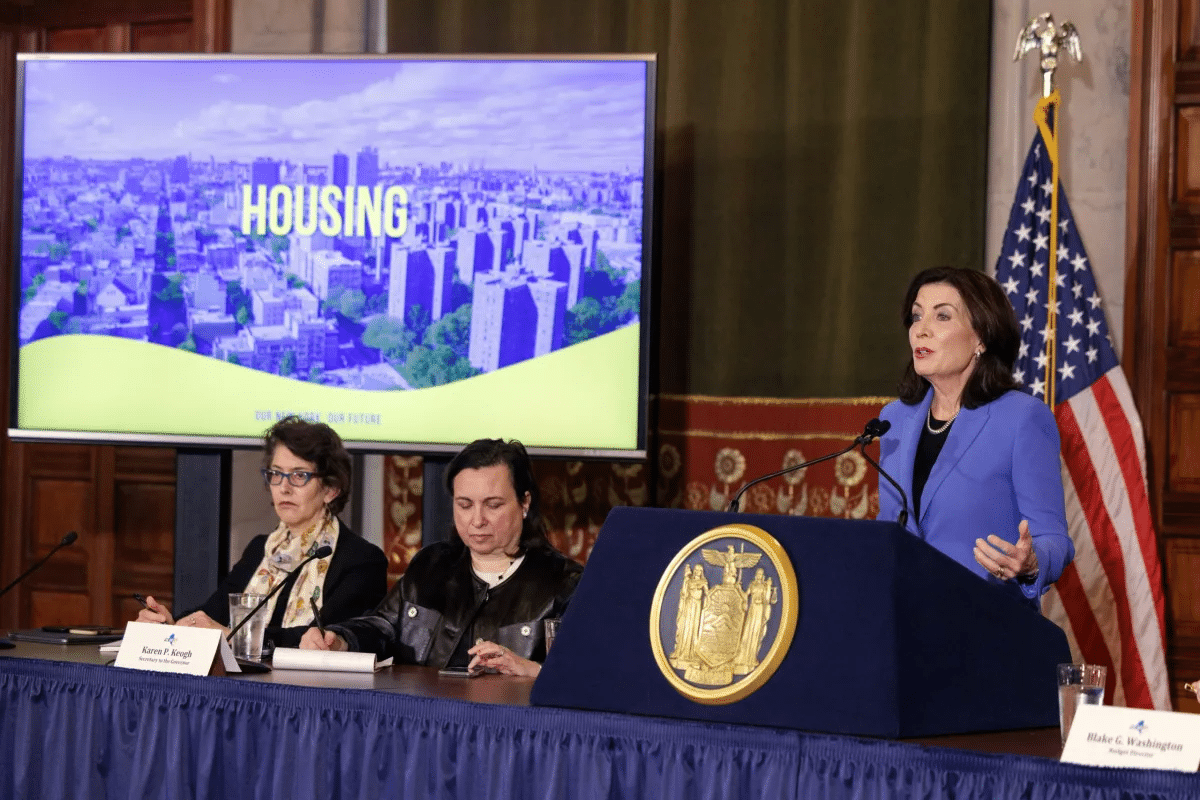

(Photograph:1903 Revival meeting. gbcdecatur.org)

What's Your Take? Leave a Comment