Walkabout: The Boss, the Wife, and the Rug Patrol, Part 1

Brooklyn Heights has long been home to some of the city’s elite, and that was never more true than in the latter half of the 19th century. Some of Brooklyn’s most important and influential people lived in the Heights, those who were kings and royal families of finance, commerce and political power. The Heights was…

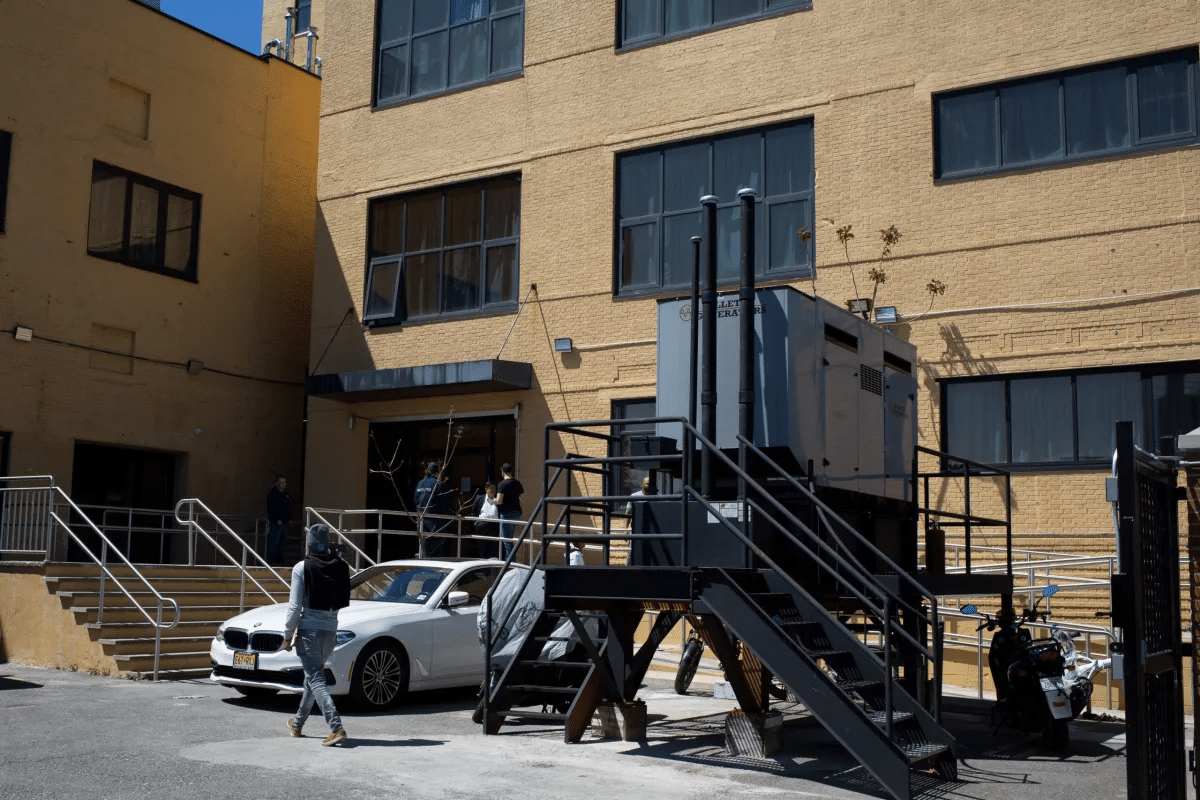

Dr. Frederick W. Wunderlich was a prominent physician. He and his wife and family lived at 165 Remsen Street, between Court and Clinton Streets, in Brooklyn Heights. Their house was a five story brownstone with a large extension in the back, like many of the other large, mid-19th century townhouses that line Remsen on the other side of Clinton. Today, this block is more commercial, and the Wunderlich house is gone, replaced by an office building that was the choice for a BOTD last week.

Dr. Wunderlich was at the pinnacle of his career, by the turn of the 20th century. He was quite well known throughout the city, was on all of the important medical boards and belonged to all of the prominent medical organizations. Had he been alive today, he would have been included in New York Magazine’s Top Doctors list. In 1890, he made the papers for his treatment of Michael Nathan, the son of Brooklyn’s Collector of Internal Revenue, Ernst Nathan.

Young Michael, in his 20s, had been struck down with tuberculosis, called consumption back then, and had been seen by the best doctors both here in NY, and in Denver, where his parents sent him for the purer air. A prominent doctor in Germany, Dr. Robert Koch, had successfully discovered the bacteria responsible for TB in 1882, (he won a Nobel Prize for this), and had come up with a controversial cure involving the injection of “lymph,” a solution of extracts and pathogens of his own devising, that sometimes worked and sometimes didn’t. This was in the days before more precise medical testing.

At any rate, news of this “cure” for a disease that killed millions of people was welcomed by all, and Dr. Koch’s Lymph was cautiously administered in the United States by only a few doctors, with the entire medical establishment watching to see if it worked. The Lymph had to be imported from Europe. The fact that Dr. Wunderlich was able to procure it, and his patient wealthy enough to afford it, is an indication of the good doctor’s standing in the community. There was no follow-up story as to whether the Lymph worked on Michael Nathan, but it certainly enhanced Dr. Wunderlich’s practice. In Germany, the solution was eventually discredited, as more patients died than lived, and Dr. Koch, who would go down in history as one of the fathers of microbiology, had to stop using it.

Dr. Wunderlich and his wife Leila were one of the wealthy families who called Remsen Street home. Next door to them at 167 Remsen was Dr. Parker, a prominent dentist, and on the other side, at 163 Remsen, was the home of Hugh McLaughlin, the powerful Democratic Party “Boss” of Brooklyn. The two men could not have been more disparate neighbors. The Wunderlich’s were from comfortable money. Hugh McLaughlin had come way up in the world. He was the son of poor Irish immigrants, people so off the grid, his birthdate was never truly established. It was assumed he was born in 1826.

Unlike Dr. Wunderlich, Hugh McLaughlin never had much of a formal education, but went to work on the Brooklyn docks as a youth, learning the rope business, doing dock work, and eventually becoming a fish monger. Like many lower income Irish workers in the mid-19th century, he was recruited by the Democratic Party bosses who offered patronage jobs in return for getting the vote, giving rise to the power of Tammany Hall in Manhattan, and its satellite in Brooklyn. In 1849, Hugh went to work for Brooklyn Party Boss Henry C. Murphy, and by 1855, had been given the patronage job of Master Foreman of the Brooklyn docks.

This position allowed McLaughlin the ability to hand out his own patronage jobs, and shore up his own base of power, so that by 1862, he was powerful enough to become the new Boss of Brooklyn’s Democratic Party, a position he held on to, with some ups and downs, until 1903. During those years, he was quite satisfied with his kingdom, and never tried to reach higher office. He had friendly relations with more powerful Democrats, such as Tammany Hall leader Richard Croker, and NY Governor David B. Hill, as well as national figures such as Grover Cleveland and Samuel J. Tilden. He was generally seen by the press and much of the public, as being hand in hand with Croker, who ruled Manhattan with an iron fist for over twenty years.

Politics, as the saying goes, was very good to Hugh McLaughlin. Like Richard Croker, he amassed a fortune through real estate, more than enough money to buy his Remsen Street house, as well as his country home in the Adirondacks, where he spent his summers, hunting and fishing. He gave to charity very generously, and he and his family were mentioned often in the society pages of the paper. He’d come a long way from the Brooklyn docks, and had succeeded in the cutthroat world of Brooklyn politics. His Republican rivals, who were just as ruthless, just perhaps a bit more polished, also played hardball, and McClaughlin’s success speaks volumes to his intelligence and battle-worn experience. But he had never come up against the likes of his neighbor, Mrs. Leila Wunderlich.

Mrs. Wunderlich had many expensive and wonderful things in the home at 165 Remsen. Among her prize possessions were many expensive and valuable rugs. Persian and other handmade rugs were quite the decorating rage in the late 1800s, so much so that layers of rugs were in vogue in the “Turkish corners” of the day, designed to evoke the harems and palaces of the exotic Middle East. All sizes were prized, and Mrs. Wunderlich had them all, large and small, in all colors and patterns.

Rugs are great and beautiful things, but they collect dirt, and dirt can destroy the fibers if not removed, and in the days before vacuum cleaners, the best way to get rid of dirt was to take the rug up, take it out back, or on the roof, on a clothes line, and beat the dirt out with a broom or wand designed for that purpose. So many people were doing this in the close confines of the city that a city ordinance was passed that stipulated that rug beating was a violation of the health code, and ignoring this would subject one to arrest and fines. The law was structured so that if a servant was arrested for rug beating, the master or mistress of the house would also be arrested, since they had ordered him or her to break the law.

This law primarily affected the upper classes, as very few working class people had fine rugs. Rug cleaning companies sprang up that would take the rugs from the premises, clean them and return them, but for many a zealous housewife, that was not going to work; it took too long and cost too much. Why bother, when there were servants, back yards, clothes lines and fences? Who’s going to tell someone what they can do in their own back yard? There are always those who don’t think the law pertains to them, so upper-class Brooklyn had developed an underground, or rather a clandestine, midnight ritual involving servants and rugs, with the poor overworked servants out in the middle of the night beating the hell out of rugs in the dark, while looking over their shoulders for the police.

In the minds of a certain segment of Brooklyn, this annoying law had made criminals out of housewives, and accomplices out of servants. It also gave rise to health department police who were charged with finding these miscreants and arresting them. In pursuit of their sworn duties, these cops against carpet abuse could be found on the street, in alleys and on roofs, looking for carpets being beaten. Over on Remsen Street, complaints had been filed by numerous people, as carpet beating could be heard up and down the block, and windows had to be closed as copious amounts of dirt and dust came in through windows, open for the summer breeze.

Hugh McLaughlin, who had probably beaten a few men up in his days on the dock, knew where the problem lay. It was next door. His next door neighbor, Mrs. Leila Wunderlich, was the worst of a bad lot; a serial rug beater. He wasn’t the Boss of Brooklyn for nothing. It was time to get the police involved. There would be investigations, some of them at midnight, intrepid reporters, and arrests. Stay tuned for the conclusion, next time.

(Photo: Elsie DeWolfe reclining in her Turkish Room, decorarts.com)

What's Your Take? Leave a Comment