Walkabout: The Bush’s, and Brooklyn’s Industry City, Part 2

Read Part 1, Part 3, Part 4, Part 5, and Part 6 of this story. Irving T. Bush was the eldest son of Rufus T. Bush; oil man, raconteur, and yachtsman. The family was descended from the Bosch family of Holland, and was no relation to the Bush family of Kennebunkport, oil and money notwithstanding….

Read Part 1, Part 3, Part 4, Part 5, and Part 6 of this story.

Irving T. Bush was the eldest son of Rufus T. Bush; oil man, raconteur, and yachtsman. The family was descended from the Bosch family of Holland, and was no relation to the Bush family of Kennebunkport, oil and money notwithstanding.

They did have several things in common though, one being legacy building. Rufus had once owned a small oil refinery on 25th Street, on the Sunset Park waterfront. He antagonized John D. Rockefeller and the other Standard Oil bigwigs with his sarcastic and highly quotable testimony in an anti-trust case against Big Oil, so they bought him out, and leveled his refinery.

The money enabled Bush to buy his champion racing yachts and life a life of luxury; a legacy passed on to Irving Bush and the rest of the family. Part One, telling Rufus Bush’s story is here. Irving could have followed suit, and done nothing more with his life but relax, but he chose to buy back the old refinery location and begin a business that would far surpass anything Rufus Bush had ever done.

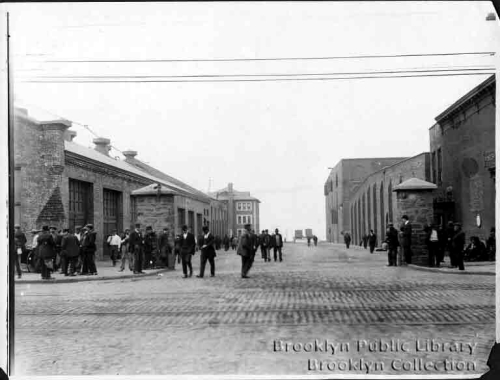

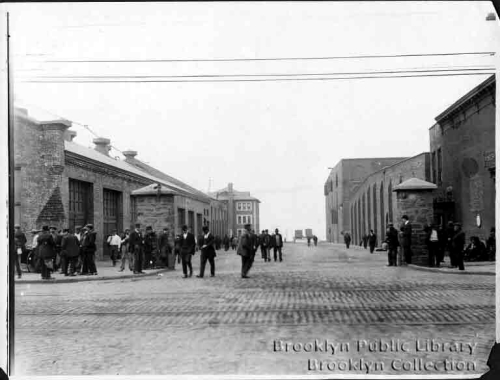

In I895, Irving T. bought six warehouses and a pier at 25th Street, the site of his father’s refinery. Under the name Bush Company, the site was a freight handling terminal, handing both rail and sea transport. When Bush first began the terminal, it was generally derided and called “Bush’s Folly,” because no one thought he would be successful in his Sunset Park location.

Rail transport to Brooklyn from Manhattan was more expensive, because the freight cars had to be loaded on a barge to get them from Manhattan across the river to the ferry slips at the terminal.

Most railroad companies refused to do it without orders of freight. After trying a test run of goods from Michigan, Bush finally secured a contract with the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad, which opened the door for other companies to follow. That got the railroad people in line.

To get the ship owners to patronize his pier and warehouses, Irving Bush leased some ships and went into the banana importing business, bringing the ships loaded with fruit directly to his pier. He made a tidy profit, as well. Soon shippers were sending their goods to Sunset Park.

In order to advertise his warehouses, Irving went into the warehouse business, storing coffee and cotton for his own company. Here again, he made a tidy profit.

The merchants got their message, and soon the Bush Company on Pier 25 was bustling. Of course, now that his business was extremely successful, his critics stopped calling it “Bush’s Folly,” and began praising Bush for his business acumen and foresight.

In 1902, the company officially became the Bush Terminal Company. The warehouses that made up the complex were built between 1892 and 1910. The railroad yards were constructed between 1896 and 1915, and the factories between 1905 and 1925.

This arrangement gave all of the Bush customers, both large and small, the most comprehensive facilities in New York; arrangements usually given only to large companies with even larger bottom lines. But here at Bush Terminal, the smallest client had access, too.

The entire venture was a huge and profitable success. By 1918, Bush Terminal owned 3,100 feet of waterfront, and covered twenty waterfront blocks. There were seven piers, each one at least 150 feet wide, and all were enclosed.

Twenty-five steamship lines used those piers, and by 1910, the Bush Terminal was handling ten percent of the steamship traffic in New York City. They soon grew and were handling 50,000 railroad freight cars, with eight piers that docked vessels from twenty-five different steamship lines.

After the freight was offloaded or was waiting to be shipped, it could be stored in one of 118 warehouses, some as high as eight stories. All of the warehouses combined could hold 25 million cubic feet of goods.

As can be imagined, all of this business was affording the Bush family a tidy fortune, one far exceeding the paltry $2 million Papa Rufus had left the clan. Irving T. got married to one Belle Barlow, and they had two daughters.

He divorced Belle, and married Maude Beard, and they had one son, whom they named Rufus, after his grandfather. This marriage didn’t last either, and in 1930, Irving married again. We’ll get to that one, and more gossip, later.

He began collecting architecture, hiring some of the period’s fine architects to design his terminal, his office building in Manhattan and his many homes. Kirby, Petit & Green, familiar to Brownstoner reader’s as the architects of Dreamland Amusement Park, and many of the suburban houses in Prospect Park South and other Flatbush neighborhoods (John Petit was the chief designer of the firm), designed the Bush family manse at 28 E.64th Street and Madison Avenue, in Manhattan, in 1905.

It was a grand and flamboyant Flemish/Jacobean design, drawing to mind the Bush Dutch family ancestry, a typical venture for John Petit. It still stands, and is appropriately, now a bank. GMAP

This mansion was only the icing on the cake. Bush Terminal, and Irving T. Bush, has a lot more to tell us. Just a teaser: Elvis was in the room!

What's Your Take? Leave a Comment