Walkabout: The Bush’s and Brooklyn’s Industry City, Part 1

Read Part 2, Part 3, Part 4, Part 5, and Part 6 of this story. The Bosch family immigrated to New Amsterdam from Holland in 1662, when Jan Bosch made the long trans-Atlantic journey to the New World. Perhaps in light of this new land, and new beginnings, the family name eventually was Anglicized to…

Read Part 2, Part 3, Part 4, Part 5, and Part 6 of this story.

The Bosch family immigrated to New Amsterdam from Holland in 1662, when Jan Bosch made the long trans-Atlantic journey to the New World. Perhaps in light of this new land, and new beginnings, the family name eventually was Anglicized to “Bush,” making them another one of the important Dutch families that contributed so much to the history of Brooklyn and New York City.

This family is in no way related to the old New England family of former presidents. Let’s get that out of the way first.

This particular Bush family settled in upstate New York, and by the 1840’s, were successful farmers. In 1840, Rufus T. Bush came into the world, and after a few years, the family relocated to Michigan, where young Rufus finished high school, and then college.

He married, and he and his wife were both school teachers for a couple of years before moving on. Like many successful people throughout history, Rufus Bush was a born salesman.

He started out selling sewing machines in Chicago, then moved to Toronto, and then to New York. He was born for a city like this.

He was now selling wire laundry line to housewives. He solicited ministers for their congregation’s membership lists, and he mailed advertisements directly to the ladies on the lists, and did really, really well. Then, like any budding capitalist, as well as that other Bush family, he went into the oil business.

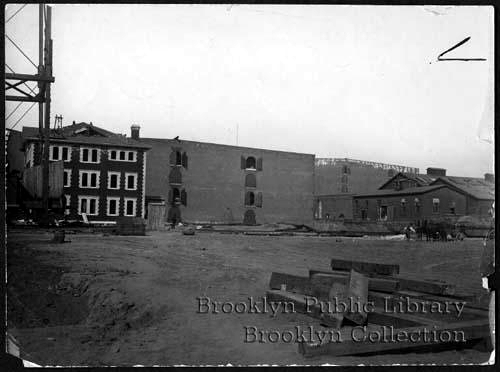

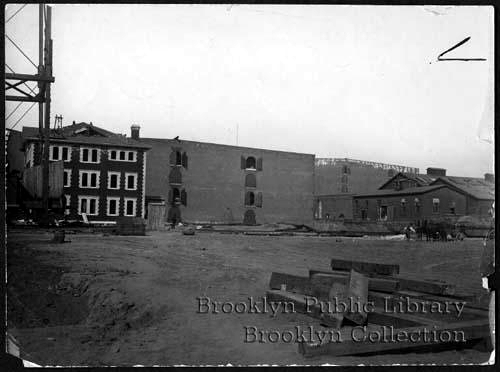

He and a partner started the Bush & Denslow Company, a single oil refinery with a plant in Sunset Park, in what was called South Brooklyn. The plant was near 25th Street. As the co-owner of a small refinery, Bush often came into competition with the mega-oil company called Standard Oil, run by John D. Rockefeller, Charles Pratt, and others.

In 1879, Rufus Bush testified in an anti-trust case against Standard Oil, supplying that trial’s most interesting and quotable testimony, much of which was quoted in the papers of the day, and survives today in the history books regarding the monopoly trials of Standard Oil and other companies.

Rufus was, no doubt, a big pain in the posterior for the Standard Oil bigwigs, so much of a pain that they made him an offer he couldn’t refuse, and bought Bush & Denslow in the 1880’s. Rufus and his partner were able to retire in extreme comfort. Standard Oil tore down the refinery.

Rufus bought a yacht. The spectacular racing craft was called the Coronet, and was built in Brooklyn. Rufus Bush made history in 1887, when the Coronet and another yacht, the Dauntless, raced across the Atlantic Ocean to Europe on a $10,000 bet. You could buy a house for less than that, so this was big money.

The Coronet won, the race took up the front page of the New York Times. Rufus and his family, including his eldest son, Irving T. Bush, then circumnavigated the globe, making stops in exotic ports of call before returning to New York.

For some reason, the Bush family sold the yacht sometime before Rufus died in 1890. Perhaps the thrill was gone. Interestingly enough, the Coronet has survived, and is in Newport, RI, the oldest registered sailing yacht in the US, and one of the last of the great wooden yachts of the 19th century. It retains its period interior, and is on the National Register of Historic Places.

Back in New York, Rufus died in 1890, after accidentally taking a fatal dose of aconite, an herbal extract commonly called monkshood. It’s an ancient remedy that can only be taken in very small doses, and is used to deaden pain.

He left his family an estate of over $2 million. They immediately formed the Bush Co, incorporating the inheritance. Irving T, who was working as a clerk for Standard Oil, could have taken his share of the money and retired, living the life of a ne’er do well Gilded Age playboy.

He was twenty-one years old. But instead, this money enabled him to begin the building of Bush Terminal, on the site of his father’s old Bush & Denslow refinery, in Sunset Park. Irving would surpass his father’s successes by building one of the largest industrial parks in the United States, which at its peak, employed over 25,000 people.

Like his father, young Irving had his fingers in many pots. In addition to clerking at Standard Oil, which I suspect was not too demanding, he was chair of the Continental Commerce Company, which held the rights to sell Thomas Edison’s Kinetoscope overseas.

This was Edison’s earliest motion picture viewer, a small device that a viewer put his or her face up to, which showed a moving image, but only to one person at a time. Still, it was a great novelty, and Continental Commerce opened the first Kinetoscope parlor in London in 1894. The association didn’t last very long, and by the mid-1890’s, Irving Bush was hard at work beginning the creation of Bush Terminal. GMAP

Seeing the vast factory complex now, it’s hard to imagine that in the beginning, the enterprise was called “Bush’s folly”. Next time, the Terminal’s beginnings and history, and the man whose big business idea helped shape 20th century Brooklyn.

What's Your Take? Leave a Comment